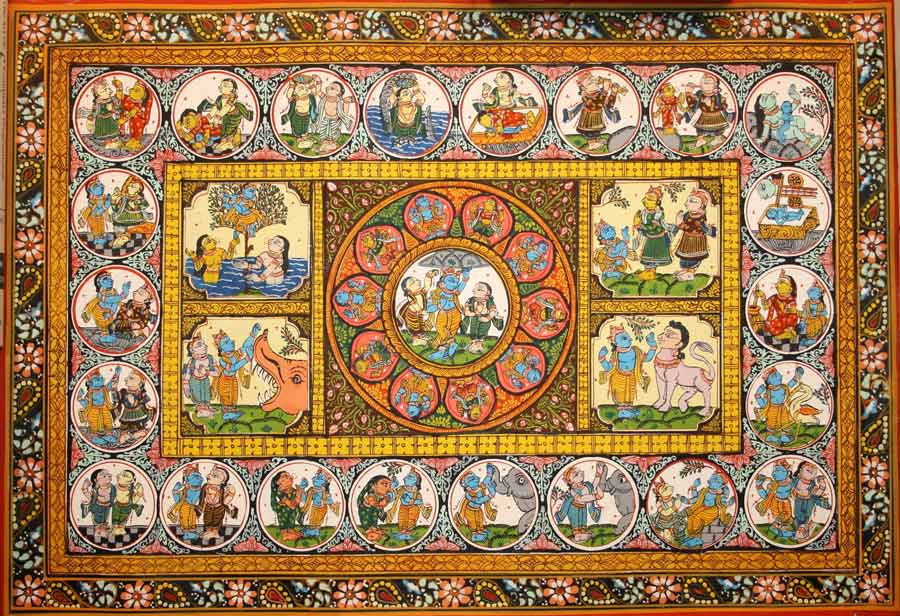

Pattachitra, Orissa, India

Editor’s Note:

This talk was originally presented at the Parliament of the World’s Religions,

Salt Lake City, October 2015.

“All has been looted, betrayed, sold” - so reads a line from Russian acmeist poet, Anna Akhmatova. She was writing about the Russian revolution, and perhaps

bleakly commenting on its failure to deliver any change to the Russian people. Or she could be cryptically writing about the death of her first husband and

fellow poet, Nikolai Gumilyov, who was shot in the forest by the Cheka in the early 1920s, for alleged counterrevolutionary activities. And then it is also

a poem about a particular spring morning, with the smell of burning peat in the air. “All has been looted, betrayed, sold” - today the line could apply to

the environmental movement or to the planet itself. The rivers and mountains are sold to the highest bidder: the water, land, and trees are treated as

commodities to be devoured. The rivers and oceans are treated as trash dumps or sewers, all in the interests of the market and unfettered growth. “All that

is solid melts into air,” wrote Marx and Engels, “all that is holy has been profaned.” Free market economies convert all good into economic good, all value

into transactional value. And yet Marxism equally disregards the natural world, equally views nature as property to be used by human beings. More

disturbingly, the environmental movement itself has become just another source for advertising copy in the phenomenon known as ‘greenwashing’. If every

company touting itself as green were actually green, we would have no climate change, no deforestation, no rivers dammed, no ocean dead zones, no mass

extinction. “All has been looted, betrayed, sold.”

“Love your Mother,” goes the bumper sticker line, with the familiar picture of the big green and blue orb of the earth. And yet the phrase has come to seem

hackneyed, trite, useless in the face of the accelerating destruction of species and habitats, in the face of the melting of the polar ice caps, in the

face of the water shortages faced by billions. According to the United Nations World Water Development Report 2015, an “estimated 20% of the world’s

aquifers are currently overexploited,” meaning that extraction exceeds the rate of recharge. Over a billion people in the world do not have the necessary

clean water for drinking and basic sanitation. At the same time, water use for manufacturing is expected to increase by 400% between 2000 and 2050, mostly

to satisfy the never-ending desire for more consumer goods. In India, farmers in Maharashtra commit suicide because they do not have enough water for their

crops, and activists in the streets protest the theft of their water that has been diverted for big hydroelectric projects. The energy is sold on the open

market, outside the country, while the rural people must leave their homes. This is not a story of India alone: the same story could be told around the

world: in the United States, in Canada, in China, in Brazil. Take a look at China’s Three Gorges dam or mountaintop removal in Appalachia or the tar sands

of Alberta. The water and the earth itself are sold on the open market by large corporations with the aid of government, which can easily be induced to do

the bidding of major corporations.

We need a powerful organizing theme capable of broad-based resistance to this alarming corporate-state takeover of natural systems. Maybe the reason the

‘Earth as Mother’ metaphor doesn’t gain more traction in the West and in the upwardly mobile classes around the world is that it hasn’t been taken

seriously enough. The trouble with myth and metaphor is that these are poorly understood constructs. The demythologizing agenda of secularism, together

with simplistic models of consciousness run roughshod over traditional modes of inquiry and may even work counter to the very foundations of consciousness,

which philosophers Lakoff and Johnson have suggested works, at a most basic level, through spatial metaphors. They write that, “mental images do not

necessarily vary wildly from person to person. Indeed, there are conventional mental images that are shared across a large proportion of speakers of a

language…a significant part of cultural knowledge takes the form of conventional images and knowledge about those images” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, 69). A

“philosophy in the flesh,” as Lakoff and Johnson aptly term their approach, takes account of our lived experience with the world in order to make sense of

consciousness.

This would seem to bode well for the idea of Earth as Mother. People in every culture can relate to mothering, and women around the world still do the vast

majority of parenting. And yet the angry Father God seems to hold sway over the nurturing, Mother God. Perhaps mothers are just too taken for granted, like

the earth itself. Just before I graduated from high school, my mother broke her collarbone in a car accident. My father had been in the driver seat at the

time, in a station wagon that had once belonged to my grandmother. Just before the SUV craze of the mid-to-late nineties, this car, an old beige-colored

Chevy, came as close to a tank as most of the cars on the road. The accident, resulting from a bad left turn, led to the car rolling over, partially

crushing the passenger cabin. I remember seeing my mother, who made a living as a United Methodist pastoral care minister, confined mostly to the couch,

lying on one side, wearing a sling. She couldn’t take a normal shower and could barely get dressed. She would mostly lie on the couch and watch television

for what I remember as four to six weeks. I remember this being quite a shock, as I had always thought of my mother as a superwoman. She had a full-time

career as a Christian minister. She received ordination in the Southern Baptist church in the 1980s, which was pioneering at the time, before switching

over to the United Methodist denomination. She visited people who were dying of cancer, who had strokes, who had all manner of life problems. She took care

of low-income people with mental illnesses and led funeral services by the score. This woman, who spent all of her time taking care of other people,

including the three children in our family and my father, now could not care for herself. I felt my world shaking, as though everything were falling apart.

The Art Shroud by Nayanna Chakrbarty

I tell this story as a point of entry into the earth as mother, Bhumi Devi. I took my own mother for granted as a child, as most children do, and I thought

of her as unstoppable. We all do the same with the Earth, thinking of it as an implacable system or set of systems that always renews itself and cannot

truly be damaged. But today the Earth’s injuries run deep, largely as a result of human haste and greed, especially the haste and greed of the global

elite, especially those in the wealthiest nations on the planet. To think of Earth as mother is not just a sentimental liberal slogan to be trotted out on

Earth Day. It is rather one of the foundational beliefs of human civilization, that today finds robust expression in Sanātana Dharma, otherwise known as

Hinduism, and in other earth-centered pagan and indigenous traditions. This same foundational belief is assaulted each day by neoliberal economics and the

death-dealing forces of globalization.

I became a Hindu because I wanted my religious beliefs to align with my belief in care for animals and the planet. I became a vegetarian at the age of

sixteen, and I saw the subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which that simple decision put me at odds with American culture and even with the deeply felt

Protestant faith in which I was raised. I went to seminary and served as a rural Methodist minister, but a growing chasm separated me from that belief

system, in which human beings are held to be the pinnacle of creation and are commanded to “subdue and dominate the earth” (Gen. 1:26,

28). Perhaps no commandment, as usually interpreted, could be so destructive, so wanton, so nihilistic. No matter how much I tinkered with liberal

theology, I just couldn’t reconcile myself to Christianity any longer. I found new mythologies, new symbols, new beliefs, and new disciplines that I felt

could be squared more easily with conscience.

I think that our current ecological moment is rather like Akhmatova’s poem, a rather bleak time in which there is not much cause for celebration. To be

sure, there is hollow techno-optimism and the usual market boosterism, but the overall trajectory is one of increased consumption and fewer safeguards for

earth, animals, and workers. If I might turn now to the Ramayana, Sita, the wife of Rama, has been captured by the tyrant, Ravana. Sita represents the

earth, the feminine side of God, the Shakti or power of God, the creation. Ravana represents unbridled greed, the greed for possessions and power. Lord

Rama represents divine consciousness, the removal of ego, the passive or contemplative side of the divine. And of course there is the epic struggle between

Rama’s army, comprised of humans, monkeys, and bears, and Ravana’s army, comprised of rakshasa demons, the embodiment of negative thoughts. The recensions

and meanings of the story are multivalent, but the meaning for us today is that the earth has been held captive to greed, and only an awakening of divine

consciousness can rouse the resources needed to fight the forces of destruction. We don’t have time to recount the entire epic poem, but I do want to focus

on a few key scenes. I will be using the Arshia Sattar translation of Valmiki’s Ramayana for this presentation, but I hope you will take the time to

revisit your favorite version.

To begin with, the Sundar Kanda, the beautiful chapter, in which the deva, Hanuman, sneaks into the demon city and is spying on its vast wealth. The story

resists classification into good and evil, angelic and demonic camps. We are told that there are good men and good rakshasas living in Lanka. There is

wealth in Lanka, there is scholarship, there is religion. While Ravana is a great figure of evil, he is learned in the scriptures, he has practiced

religious austerities, and he can claim rightfully to be a king. His vice lies in taking things too far, in wanting to rule not only the earth but the

devas as well. He wants not only wives for himself, but Shri Ram’s wife. We are told that Ravana lives in the midst of great beauty. This passage is from

Hanuman’s spying mission:

The king’s palace, guarded by deferential rākṣasas, overflowed with lovely women who were like jewels, and it murmured like the ocean with the tinkling

of their ornaments. The air was fragrant with sandal and other rare unguents and filled with the music of drums and conch shells. Worship and sacred

rituals were performed here regularly…There were thousands of golden vehicles and heavily-carved palanquins that shone like the sun. There were

vine-covered arbours, opulent rooms, picture galleries, recreation areas with hills fashioned out of wood, pleasant sitting rooms and lavish bedrooms.

(416-417)

The description goes on like this for some time. In short, the Lanka fortress is so splendid that not even a dot com billionaire could imagine its wealth

and luxury. It is a city of brawling and licentiousness, but it is also a place of learning and piety.

But none of this wealth holds any beauty for Sita. She willingly followed Rama into his forest exile, trading the comforts of Ayodhya for a simple forest

hut. Rama and Sita are inseparable: they are the twin aspects of the divine nature, they are Vishnu and Lakshmi, and yet, somehow, things have gone off

course. The impossible has happened. This valiant kshatriya’s bride has been stolen by mahayogi Ravana. She is held captive until she agrees to marry him.

Hanuman searches diligently until he comes upon Ravana’s pleasure garden, where he finally finds the distraught Sita:

He saw a beautiful woman surrounded by rākṣasīs. She was wearing a dirty, soiled garment and was thin and pale from fasting. She sighed deeply again

and again but she shone still like a moonbeam in the bright half of the lunar fortnight even though her beauty was diffused, as a flame is dimmed by

smoke. Her yellow silken garment was fine but worn and without any jewelry, she was like a pool without its lotuses. Her sad face was tear-stained, her

hair hung down her back in a single braid.

(430)

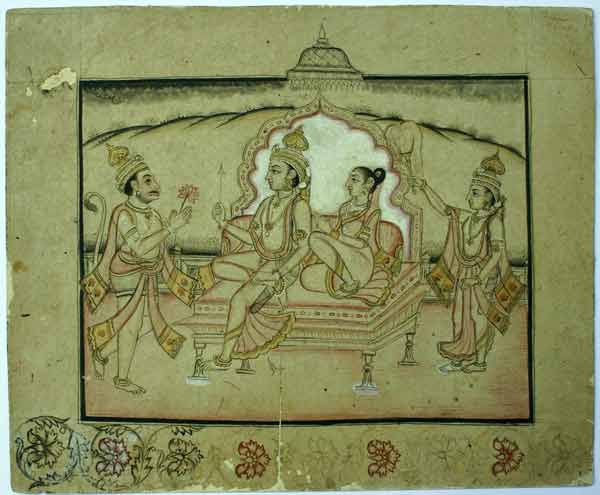

On a throne sits Rama holding an arrow, Sita beside him, as Hanuman clasping a lotus flower

offers repsects, chauri-bearer in attendance. Datia, circa 1820.

And most of you will know how the story goes. Sri Hanumanji brings Sita Rama’s signet ring in token that he has vowed to rescue her, that his army is on

its way. And Hanuman burns down the demon city, the tyrant Ravana is defeated, and Rama and Sita are reunited. They return to Ayodhya with great fanfare.

Today I want to stop here, in the ashoka grove, with Sita sitting there weeping. She does not yet know that the army will soon come to rescue her. She must

be wondering why Lord Rama has abandoned her. She must think that he may not even know that she is still alive. At this moment, there are only tears. On

the other side of the ocean, there are tears as well, the tears of Rama and Lakshmana, the tears of the monkeys and bears, who cannot find Sita, although

they wander all over the subcontinent. With Hanuman alone lies hope, for he has remembered his divine nature. He knows himself to be the son of Shiva and

the son of the wind. He will not disappoint Rama: he will succeed in his mission. He will help Rama in his vow to rescue Sita at all costs.

To bring this back to our current ecological crisis, we are now at the moment when the earth itself has been held captive to devouring greed. We live on a

planet of great wealth, and great beauty, but those resources have been put to corrupt ends. The battle of the Ramayana is happening now. It happens when

everyday people rise up against the theft of their land and the poisoning of their water. It happens when the people of India rise up against the death of

their sacred rivers. It happens when people in North Dakota fight the big fracking companies. It happens whenever people of conscience of any tradition,

religious or secular, strive to put the earth back onto a good footing and leave the world a better place for their children. Let me say a little bit about

this war and the nature of the struggle. First of all, it need not mean literal warfare. Let me just give three quick principles. 1.) The warfare happens

first within. This is Lanka, this is Kurukshetra. We must look within our own hearts to remove the passion and anger, the desire and greed. We must become

more simple, for our own sake and for the sake of the world. We must learn to care for ourselves in simple ways rather than in the ways offered to us by

consumerism. 2.) Religion and science must become more harmonized. We must look to scientists to understand what is happening to our climate, to our

rivers, to our land. We must then take that knowledge and make it a matter of religious merit (punya) to care for the earth in ways that will make a

positive impact on the earth’s systems. 3.) Some people will engage in direct action, through protests, strikes, blockades, and lockdowns. Those who can’t

put themselves on the front lines can still do something, through teaching and writing, through letter writing and petitions, through learning sustainable

lifestyles. These three principles will not be the end of the battle, but they will get us started in the right direction.

One of my teachers, Brian Mahan, talked about epiphanies of recruitment. That is what we are all experiencing now. In the words of the Christian

scriptures, “the earth itself cries out” to us (Rom. 8:19). She is sitting there in tears, in Ravana’s garden, eagerly calling out for rescue. We are

Rama’s army. We are the only army he has. Not only humans, but the animals as well, and the earth itself, which struggles to bring into view a new way of

living on the planet. The satya yuga wants to be born, and we can play a small part in making it happen. To return now to Akhmatova’s poem, Let me now turn

to the rest of the poem:

All has been looted, betrayed, sold; black death’s wing flashed [ahead]; all is gnawed by hungry anguish—why then does a light shine for us?

By day a mysterious wood in the vicinity of the town breathes a scent of cherries, by night the depths of the transparent July sky glitter with new

constellations.

And the miraculous is coming so near to the ruined and filthy houses, something nobody, nobody has known, though we have longed for it from time

immemorial.

The earth cries out for us. Sita’s tears fall to the ground. The only question is whether we will hear her cries, take to heart the mission that Sri Rama

has given us, to reclaim his bride and bring her back to the city where there is no war.