Nearly everyone is aware of Coleman Barks’ bestselling English versions of the Persian poems of Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī, and most educated readers of Barks are

by now aware that his “translations” are not translations at all, Barks having no Persian: they are retooled versions of earlier English translations. [1] But we forgive Barks the false advertising found on the title pages of his works (“translations by

. . .”) because he has several times in print admitted the truth of the matter, and because his poems based on Rūmī’s are so often very good, providing

spiritual inspiration without departing too far from the original.

We have examples in the same field of clear-cut intellectual dishonesty, however: Daniel Ladinsky has published several volumes of poetry that claim to be

versions of Ḥāfez Shīrāzī (aka Hafiz), but scholars of Persian can’t seem to identify which of Hāfez’s poems inspired which of Ladinsky’s, so distant are

the latter from the former. Indeed, polyglot translator A.Z. Foreman has written a lengthy, scathing review of Ladinsky that argues he is simply an

out-and-out fraud passing off his own work as someone else’s (since that someone else is so much more prestigious). [2]

Both Barks’ and Ladinsky’s publications exist at different places on the spectrum of cultural appropriation, which essentially refers to a member

of one culture borrowing elements of another culture and repurposing them in a way that to some degree distorts their meaning—often in a way that indicates

that the appropriator is ignorant of, or insensitive to, the meaning of those cultural elements in their original context. Going further, cultural

appropriation is viewed in postcolonial and feminist theory as oppression when the borrower is the member of the cultural majority and is

appropriating from a marginalized or minority culture, such as one that was previously colonized by the majority culture (e.g. India).

The American yoga and kirtan scene is of course rife with cultural appropriation that implies insensitivity to traditional Indian culture. This fact is

spoofed in clever Internet memes like ‘Gandhi Does Yoga’ and exemplified by privileged white “kirtan artists” that mispronounce, mistranslate, and even

fabricate mantras, as well as by countless American “yoga” teachers that have only the most superficial understanding of the cultural background of the

very practice they are trying to teach.[3] Some appropriators, like Leslie Kaminoff, justify their

appropriation with specious arguments that yoga is not really Indian because it is part of nature

itself, and therefore was not invented but only discovered by Indians.[4] In fact, though yoga addresses and

interacts with biological bodies and minds, it is a cultural product and can only be understood with reference to the culture that birthed it and shaped it

for 99.9% of its lifetime so far. People who comment on the nature of yoga based on their knowledge of literally 4% of its history are displaying not

only unintentional hubris, but also lack of awareness of the degree of education required by the tradition itself in order to be qualified to

speak on it and represent it.[5]

Sutra Journal has, since December, been publishing the work of Lorin Roche, an author and poet who I argue is also a cultural appropriator, one closer to

Ladinsky than Barks on the spectrum because like Ladinsky he is, in my view, guilty of a subtle kind of intellectual dishonesty as well. The present

article seeks to demonstrate the validity of these statements.

--- Let me take a moment to applaud Sutra Journal for being willing to publish authors with opposing views, since this generates the stimulating debate so

vital to the contemplative and intellectual life. ---

Specifically, Roche has appropriated a medieval Sanskrit text whose original title is the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra (literally, “The Scripture of

the Bhairava who is Consciousness”)[6] and re-presented it as The Radiance Sutras, a book of

original Roche poetry presented in juxtaposition with the original Sanskrit text of the Vijñāna-bhairava in a move clearly calculated to imply to

the reader that it is a translation.

Now, since Roche knows well that the majority of his fans and followers assume he does understand the language, and he is careful not to disabuse

them of this assumption, wouldn’t this be a case of blatant intellectual dishonesty? It would, except for the fact that Roche believes that what

he has produced is just as valid as what any professional Sanskrit scholar might produce. This is because he believes that the text of the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra mystically speaks to him and reveals its inner meaning directly, without necessity for grammar or book-learning. I will

explain below exactly how he goes about producing poems that often have little relation to the Sanskrit text while yet believing he has produced a valid

translation that captures the essence of the text.

The purpose of this article is not to attack Lorin Roche as a person; through mutual friends, I hear he is a warm-hearted individual and a good man, and I

am sure he has the best of intentions. Rather, critically examining Roche’s particular form of cultural appropriation will reveal to us fascinating

features of the American spiritual landscape and help us to understand how different that landscape is to that of India 1200 years ago, and why American

appropriators nearly always distort their Indian sources. Secondly, it will reveal (and explain) some common misunderstandings about the nature of the

Sanskrit language. Finally, it gives me the opportunity to offer suggestions to Westerners about how to approach the spiritual technologies found in

Sanskrit sources for personal spiritual benefit while simultanously respecting the source culture.

Why I am so interested in Roche’s appropriation in particular, when he is far from the most egregious appropriator? Because the text that he appropriates

is a central scripture of the Trika lineage of Śaiva Tantra, a lineage which I study professionally as well as practice within personally. It has therefore

disturbed me to see a sacred text of yoga from my tradition presented to the Western public as little more than a justification for hedonism

(i.e., mental or sensual pleasure as an end in itself). Even more importantly, I am concerned to alert readers to the fact that the real teachings

of the Vijñāna-bhairava, correctly translated, are doorways to liberation much more powerful and precise than readers of The Radiance Sutras could suspect.

Therefore in this article I attempt something unusual: it is both a critical commentary by a professional Sanskrit scholar and a demonstration that

scholarship and spiritual sensitivity are not mutually exclusive. I hope to provide the reader with a direct link to the teachings of the original

scripture and show that accurate translations can also be spiritually powerful. In this way, I hope to demonstrate that last century’s divide of scholarly vs. inspiring, accurate vs. juicy, intellectual vs. spiritual is no longer relevant. It is time to restore the connection

between intellectual rigor and spiritual inspiration that characterized Indian literature before foreign conquest. This article is a small contribution in

that direction.

First we will address specific problems in translation and cultural mediation, then I will present examples of accurate translation from the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra, then discuss the implications of all that we have considered.

When spiritual practitioners who are not also trained intellectuals attempt any kind of translation or re-rendering of a foreign work (especially one from

the ‘mystic East’), they often read into the text what they wish to find there, while being unable to see that they are doing so, because of lack of both

linguistic competence and lack of historical awareness. In the case of Roche, many of his distortions of the original source are due to his (possibly

subconscious) desire to find his personal philosophy of hedonism in every verse of the Vijñāna-bhairava. [9]

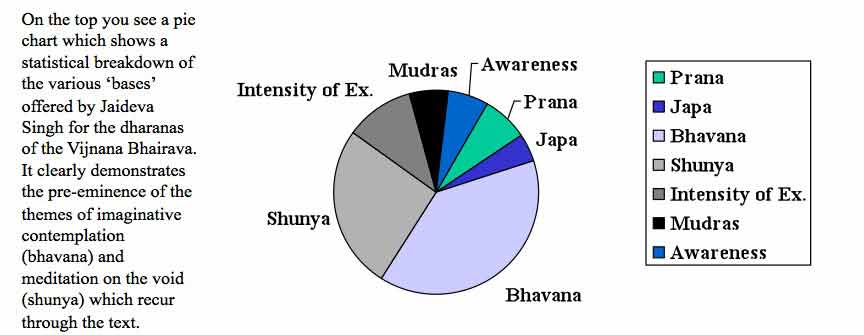

Notes: this chart, which I made a long time ago, is slightly misleading in that ‘Awareness’ should read ‘Pure Awareness’ (since

all

of the dhāraṇās involve awareness). In ‘Intensity of Ex.’, the Ex. stands for ‘experience’. Bhāvanā can also be translated as ‘contemplative

meditation’.

Roche reveals his Shakti-bias when he writes, “Each of these techniques is a way of attending to the rhythms, pulsations, and sensuousness of the divine

energy that we are made of and that flows through us always.” In fact, more than a quarter of the dhāraṇās (meditative techniques) in the text

focus on Shiva as the still silent void (śūnya) of pure awareness (see, e.g., vv. 43-49 and 58-60)! This seems to be almost a no-go zone for

Roche, who thus must do violence to his source in producing the poems he wants to attribute to it. He also wrongly states that “The language of the text

abounds in earthy humor and sexual innuendo,” again projecting his own predilections and preferences onto the scripture. (I’m sure any fluent Sanskritist

would agree with me that there’s little to no sexual innuendo in the text, though there are a couple of obvious verses about how to meditate on

sexual pleasure.)

Finally, he mischaracterizes the text as being unconditionally permissive,[11] when in fact it presupposes

the mental and physical discipline standard to all forms of yoga in the medieval period. In this he is simply dragging the text toward his

worldview, formed as it was in late 60s/early 70s California, an era prominently characterized by a “do whatever feels good” ethic and intensified sensual

experience through psychedelics, both of which are apparent in his poetry. Though the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra certainly did greatly open up the

traditional range of possible doorways to the Divine, and is acknowledged as atypical and revolutionary for its time by scholars, it assumes a capacity for

subtle perception, self-awareness, internal quiet and self-control not typically found in the American yoga scene to which Roche’s book is marketed.

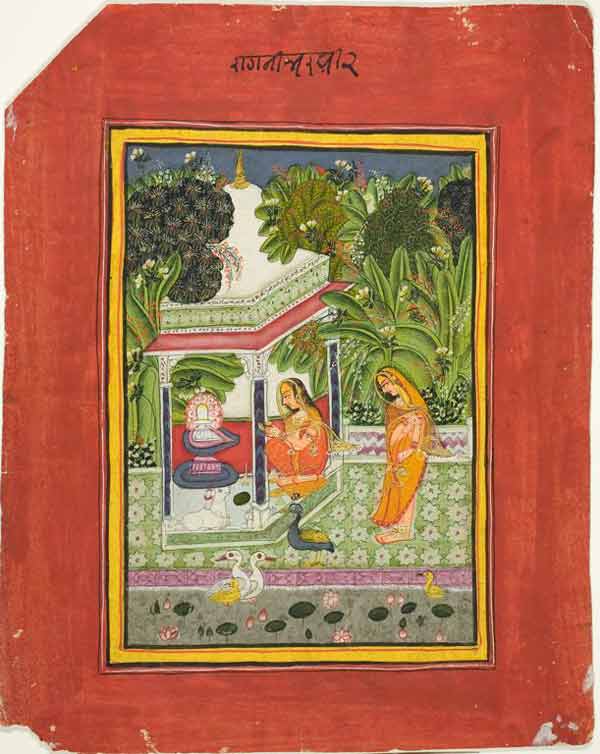

Bhairavi raga

The Problem of a mystical, anti-intellectual approach to Sanskrit

Needless to say, the risk of confirmation bias is greatly reduced if one can fluently read the language one proposes to render into one’s native tongue. [12] Here is where Roche exhibits intellectual dishonesty, for he speaks to his readers as if he is an

expert in Sanskrit language and literature when he is not,[13] as is obvious to anyone who’s studied the

language at the university level. Since he tells us he’s studied the text closely for the last thirty years, one wonders why in the world he didn’t bother

to do one or two years of university-level Sanskrit (e.g. at U.C. Santa Barbara, almost in his backyard), which is all it would take to understand the

register of Sanskrit used by the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra.[14]

The answer to this question is startling, and personally leaves me astonished. Roche, like many American yogis, regards Sanskrit as a mystical language,

and clearly believes that unlike other languages, it yields its secrets to any sufficiently mystical person (like himself) without the need for

intellectual study (see endnote 15 for the evidence that this is really his view).[15] This, then, is his

method of ‘translating’: he memorizes a verse and repeats it over and over to himself (sometimes for weeks on end), then he looks up each word in a

Sanskrit-English dictionary and writes all the possible meanings found there on note cards and spreads the cards out on the floor (up to 250 cards per

verse) in a mandala-formation and then walks around and around them “until I feel the richness of the words vibrating in my body. Then I start to pray for

English words . . .” until a poem takes shape that uses as many of the words on his note cards as possible. [16]

This approach, admired by his followers for its thoroughness, reveals some common misunderstandings about the nature of Sanskrit. First, Roche is

fascinated by the polysemous, multivalent nature of the language; that is, the fact that most words have many different possible meanings. But he is

clearly unaware that only one of these meanings applies in any given context. I’ll explain. The dictionary he uses (Monier-Williams’ Sanskrit-English Dictionary, 1896) gives all the meanings a given word has ever had over millennia, including technical terms limited to specific

branches of literature as well as unattested meanings (i.e., those found in ancient Sanskrit lexicons but never actually used in texts). A Sanskritist

usually knows which meaning is relevant based on context. For example, the word tantra means ‘loom’ only in the context of a discussion

of weaving; in spiritual contexts, it means ‘doctrine’ or ‘framework’ or ‘system’ or ‘scriptural text presenting a specific doctrine and system of

practice’ (the latter being a usage specific to the Tantric movement). Like many other modern authors, Roche thinks that ‘loom’ or ‘weave’ is the primary

meaning of tantra because it occurs first in Monier-Williams’ dictionary (MW), but in fact, MW lists the oldest meaning first, not the

commonest meaning.[17] A Sanskrit reader who sees the word tantra in a spiritual text doesn’t

think of a loom any more than an English reader seeing the word ‘bark’ in a book about trees would think of a dog. And this is a crucial point: the

Sanskrit dictionary lists homonyms under one and the same entry; to think that any of the meanings could apply is as absurd as confusing the

meanings of the three distinct definitions of the English word ‘bark’ (relevant to the specific contexts of trees, dogs, or boats) or ‘key’ (relevant to

the specific contexts of locks, music, or islands).

Context determines which meanings are possible, yet Roche imagines that all the meanings found in the dictionary under a given word are relevant.

(It’s a strange error to make, since it implies confusion not only about the nature of Sanskrit, but about the nature of language generally.) This is why

he thinks that in the scripture under discussion “there are multiple layers of information reverberating in each word,” and further claims that “hundreds

of very different translations could be done. This is intentional.” In other words, he claims to know the intention of an author writing centuries ago in a

language that he doesn’t read!

In fact, his claim is fallacious. While translators equally competent in the language might debate about the intended meaning of verses that are

purposefully mysterious (as some are in the VBT), half a dozen competent translations would exhaust the range of possibilities. And not being sure of the

author’s intended meaning in every case is not the same thing as saying that the author intended many meanings. (In the case of the VBT, I am sure

s/he did not.) Sadly, we do not yet have even one translation of this text by a competent Sanskrit who is well-read in the literature that

parallels the VBT.[18]

Since many non-Sanskristists consult the MW dictionary, let me note here for their benefit (and Roche’s, if he reads this) some conventions MW uses:

· a definition followed by ‘L.’ is lexicographical, meaning that the word is never actually used with this meaning, despite the meaning being

listed in ancient lexicons

· a definition followed by ‘ifc.’ is only applicable if the given word is the last member of a compound

· meanings are listed in chronological order, so the first meanings are unlikely to be relevant unless you are reading a Vedic text. Meanings of words

shift over time, rendering older meanings obsolete or nearly so, but MW lists them as well. (Remember the text we are currently considering was written

2000 years after the Vedic texts, during which time there was plenty of gradual semantic drift, even in the slow-to-change Sanskrit language.)

Secondly, Roche wrongly thinks that the author of the VBT is constantly using the literary device of śleṣa: punning, double entendre, or

paranomasia. Not being a Sanskritist, he doesn’t understand what śleṣa actually is: for example, commenting on verse 1, he says: “If we

wanted to, we could hear mayā as word play (śleṣa), with the similar sound māyā.” This comment is revealing,

since that is absolutely not how śleṣa works. Mayā (“by me”) and māyā (“magic, etc.”) are unrelated

even if they sound similar to an English ear. Roche’s mistake is as basic as confusing the word ‘art’ (kalā) with the word ‘time’ (kāla).

In fact, śleṣa works by creating contexts in which two or three distinct meanings of a word are more or less equally applicable,

confusing the reader for a moment until his confusion turns to delight upon realizing the word-play. For an explanation and ingenious example of Sanskrit word-play, read this blog post. The author of the VBT rarely uses sophisticated

literary devices like śleṣa, wishing as he did to reach a wider audience of initiates, not all of whom were literary aesthetes.

Revealingly, Roche tells us: “I refer to The Radiance Sutras as a 'version’ rather than a ‘translation’ because I am following a different set of

rules than those developed by Indologists . . .” — that is, his own set of rules, rather than the rules of Sanskrit grammar. Yet he pretends to authority,

repeatedly implying that his poems are as valid a translation as any other, and displays them in his book under or side-by-side with the original Sanskrit

verses so as to imply that they ARE translations (see the image below). This is intellectual dishonesty, in my view; though there are some who disagree

with me.

In summary, then, Roche is an aesthete writing a book of beautiful poetry inspired by a text unconcerned with aesthetics, its sole purpose being to provide

seekers of liberation with new technologies. This is why his book does not represent or even correspond to the intention of the author of the VBT.

Discussing these issues provides us with a much-needed opportunity to illustrate the level of qualification needed to interpret Sanskrit texts. In the

original tradition, you had to master grammar (vyākaraṇa) before you could study any other art or science (śāstra) documented in

texts, for obvious reasons. Educating the wider public is a crucial mandate, lest people interested in Sufism study Ladinsky’s poems or people interested

in Tantra study Roche’s poems, both of which would be a waste of their time, despite the beauty of those authors’ poems.

Indeed, most of those who view my critique of Roches as harsh do so because they find pleasure in his poems. There’s nothing wrong with that—I like some of

them myself. But that is a completely separate issue. The poems have literary or artistic merit on grounds completely unrelated to whether they

convey the intentions of the author of the VBT. Anyone who authentically loves the poems will love them even without the superimposed mental frame

that they communicate the wisdom of an ancient text. And it’s only fair of me to point out that occasionally the poems do allude to or align with

the actual practice being taught in the corresponding Sanskrit verse, because Roche has studied all the available translations, and therefore, sometimes,

accurate pieces of translation are echoed by a given poem.

But here is the main point: readers who believe that they are accessing ancient wisdom by reading The Radiance Sutras (and after reading Roche’s

introduction to the book, who could blame them?) are being misled. It is a disservice to them to make them think that by reading this book, they have

access to the teachings of the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra. They most certainly do not, and since those teachings deserve to be known (in my view), an

article setting forth the facts and offering accurate translations (for which see below) seemed desirable.

One of the readers criticized Matthew Remski’s Threads of Yoga, a ‘remix’ of the Yoga-sūtra, with these words: “The

reader is robbed of the work that will bring her insight—wrestling with the difficult ideas in the text—and instead invited to swoon for a poet.” This

exactly what I think is happening in Roche’s book.

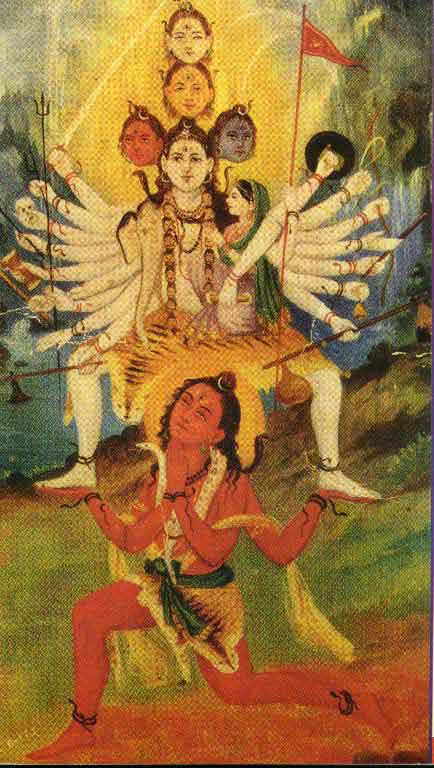

Bhairava, Kathmandu, Nepal

The real meaning of the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra

Before addressing the wider cultural implications of Roche’s approach to spiritual literature, let us spend a few moments with the scripture itself. The

profound (and surprisingly modern) spiritual teaching of the scripture begins with verse 13, but Roche makes much of the first line of the text, wishing to

find in its simple language much poeticism. He renders śrutaṁ deva mayā sarvaṁ rudra-yāmala-sambhavam as “Shining One, I have heard that which has emerged from the intercourse of Rudra and his Shakti.” Now,

this is actually very close to the Sanskrit, as it happens; but rather importantly, it’s missing the subject of the sentence. In fact, the first line is

not a complete sentence. The logical subject (trika-bhedam) is found at the beginning of the second line of the verse, agreeing with sarvam in the first line. With it, we can translate the literal meaning of the sentence:

“O Lord (deva), I have heard (śrutaṃ mayā) the whole teaching of the Trika lineage (sarvaṃ trika-bhedam) that was

produced from our divine union (rudra-yāmala-sambhavam).”

The very first sentence of the scripture declares its context, a context appropriators like Roche prefer to obscure: it is a work that situates itself

within the Trika revelation of the Tantric movement. The primary deity of the Trika is Parādevī, a Tantric form of Sarasvatī. [19] This first sentence also declares the Kaula theology of the text, focusing as it does on the union and

balanced harmony of the apparently contrary complements Śiva and Śakti. Yet as noted above, Roche skews this balance in his poetry,

consistently privileging Shakti over Shiva, in accordance with the cultural bias of Californian yoga.

Let us go deeper. In the following verses (2-7), the Goddess asks about the ultimate nature of reality, and inquires whether it is encompassed by any of

the deities or mystical concepts revealed in the scriptures.[20] Surprisingly, Bhairava responds by saying,

Know that the embodied forms of the Divine that I have taught in the scriptures are not the real essence [of the Tantras], O Goddess. They are like a

sleight-of-hand, or like dreams or illusions or castles in the sky, taught only to help focus the meditations of those who are debilitated by dualistic

thought, their minds confused, entangled [as they are] in the details of ritual action.

(vv. 8-10)

He denies that any of the technical terms she has introduced encompass the true nature of reality, continuing,

These were taught to help unawakened people make progress on the path, like a mother uses sweets and threats to influence her children’s behavior.

[21]

Know that in reality, the one pure universe-filling ‘form’ of Bhairava is that absolutely full state of being called [Goddess] Bhairavī: it is beyond

reckoning in space or time, without direction or locality, impossible to indicate, ultimately indescribable, a sense-field free of ideation, blissful

with the experience of the innermost Self

(antaḥsvānubhavānandā).

When this is the ultimate Reality, who is to be worshipped, and who gratified? This state of Bhairava called Bhairavī is taught as supreme; it is

proclaimed to be Parā Devī in her ultimate nature.

(vv. 13-17)

In other words, the absolutely full state of awareness (bharitākārā avasthā) which Bhairava describes is the immediacy of a joyously expanded

field of awareness free of mental filters or projections; the opening to and welcoming in of the whole of the present moment without conditions; the

granting of the heart’s consent to the moment as it is, releasing mental fantasies of how it could or should be; and the feeling of deep connection and

presence that comes from surrendering into true intimacy with the qualia of reality as it offers itself and permeates awareness now. In this

state, one’s innermost being (antaḥsva) is revealed as it really is, permeating the whole of reality (viśva-pūraṇa)—an experience that

fills one with joy (anubhavānanda).

The radical nature of this revelation could only be appreciated through familiarity with the cultural context of the time, in which revelations of

ever-more esoteric deities was a game of sectarian one-upmanship. A plethora of complex ritual forms and injunctions is at once done away with in a

profound reframing of the purpose of spiritual practice: when we access the state of inner fullness, the state of liberated and expanded awareness, we are

engaged in the highest worship possible. This teaching became popular later and is still popular today, but in the year 850, it was unheard of. It was a

revelation.

Svacchanda Bhairava

The practices of the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra

In response to Bhairava’s teaching, the Goddess, as pragmatic as most yoginīs I know, asks:

“O God of gods, answer me this in such a way that I can completely understand it: How is this state of absolute fullness of the Divine—beyond space, time,

and locality, and impossible to represent conceptually—attained? By what means can one enter into it? And how does Parā Devī, the Supreme Goddess, become

that [entryway], O Bhairava?” (vv. 22-23)

Bhairava’s reply is the 112 techniques, practices, and contemplations that form the bulk of the scripture (vv. 24-136). These come in no particular order,

but it does seem significant that the first practice presented is a sublime meditation on the spaces between the breaths:

The Supreme Goddess [constantly] articulates herself as the creative flow of breath:

apāna (inhale)—the movement into embodiment—descending, and prāṇa (exhale) rising up. By ‘nourishing’ the two points where the inbreath and outbreath arise, that moment of stasis reveals Her in fullness. (v. 24)

This verse poses a fascinating challenge for the translator, because it is impossible to render it correctly without knowing the technical terminology of

Śaiva Tantra. For example, jīva means both the inhale and the creative ‘downward’ movement into individuality. Also, uccaret means both

to breathe (especially exhale) and to utter a mantra in sync with the breath. This is a usage not found in the dictionaries, since it is specific

to Śaiva Tantra.

By not turning back the inner and outer breaths [too soon] from the pair of spaces [where the breath pauses], the form of Bhairava [i.e. pure

awareness] manifests thus through Bhairavī [i.e.

prāṇa-śakti]. (v. 25)

The ‘pair of spaces’ refers to the two points mentioned in the previous verse: that from which the inhale begins (which is outside the body) and that from

which the exhale begins (deep inside the body). The inside of the body is visualized as open space, mirroring the outside. One is invited to pause ( kumbhaka) at the end of each inhale and exhale and experience the spaciousness of pure awareness.

Neither moving forth, nor entering in, the power (

śakti

) inherent in the breath is revealed in the Center [where it comes to rest]. Then, through the dissolution of thought-forms, the Bhairava-state

[appears].

(v. 26)

The ‘Bhairava-state’ is an experience of ‘emptiness’ that is paradoxically filled with the quiet intensity of pure presence. This experience happens in

‘the Center’, which of course refers to the central channel, the subtle core of one's being.

She moves out and rests; She moves in and rests. When the breath-power becomes still after exhalation or inhalation, then that [state] called 'peaceful

repose' (

śānta) [appears]. By that power [of the breath], peaceful [Shiva] reveals himself. (v. 27)

For whatever reason, I haven’t seen this verse translated correctly so far, and it’s just lovely. (An aside: taken together, these four verses seem to

undermine the text’s claim to teach 112 techniques, since here we seem to have one practice described and variously nuanced over four verses. I find other

instances where two or more verses are needed to explain a practice as well.)

Now we can at last turn to the handful of verses that Lorin Roche has written about here in the virtual pages of Sutra Journal. In his first article (Dec.

2015), Roche attempts to poetically render a difficult and subtle verse, #32. He presents his poem as a playful rendering, yet also claims to know the

inner meaning of the verse.[22] Literally, the Sanskrit

means:

“Meditating on the Five Openings as the colorful circles of the peacock’s feathers, one enters the Heart, the Supreme Space.” [23]

This obviously needs explication; traditionally, when unsure of the intended meaning, one looks first to the Sanskrit commentators on the root-text. A

Western appropriator like Roche is of course less likely to honor the strong cultural tradition of first consulting what earlier authorities have to say

about the verse. Fortunately, we have two such authorities to consult, Śivopādhyāya and Ānandabhaṭṭa. After pondering their opinions and consulting my

practitioner’s intuition, this is my interpretation of the meaning of the verse:

We first note that the five[24] sense apertures are commonly called ‘spaces’ or ‘openings’ (śūnya

), but they are separate, whilst the five circles (maṇḍalas) of the peacock’s feather are nested one inside the other. Since we are instructed to

meditate on the sense-apertures as the circles on the peacock’s feathers (a point missed by all available translations), that clearly implies that

we should allow the sense-fields to merge. The idea may be to intentionally nest the subtler sense-energies inside the coarser ones (i.e., sound-sense

nested inside touch inside visual-sense inside taste inside smell); or perhaps that level of detail is not intended here, and you are simply supposed to

let them all merge into a single sensual field, as if you had a single sense-aperture.[25] All phenomena

within the sense-field, then, are to be perceived as vibrations within vast emptiness (the ‘Supreme Space’), the innermost Heart of Being, pure Awareness

itself (= Bhairava).

Now, at the center of the nested circles of the peacock’s feather (see image), you see an incredible iridescent cobalt blue, and probably not

coincidentally, this is the traditional color of Anuttara Śiva, absolute consciousness. The verse explicitly says that through this meditation, one enters

the anuttara śūnya, the Supreme Space, the absolute Heart. As far as I know, no one has noticed this correspondence yet.

Verse 39 offers another example of a very specific yogic practice important to the tradition but unknown to Roche (and unknown to most translators as

well). The verse clearly alludes to the central Tantrik practice of uccāra, in which the yogī repeatedly devotes a prolonged exhale to a

single-syllable mantra (praṇava or bīja) such as Oṃ. Specific techniques are involved with this practice, and the scripture is not

innovating when it invites the practitioner to meditate on the silence immediately following the prolonged sound of the mantra. Through this meditation, we

are told, the yogī attains perfect emptiness (śūnyatā). In all fairness we should here note that the Roche poem inspired by this verse is not only

aesthetically pleasing, but actually is fully aligned with the original intention of the verse; though of course he cannot convey the subtleties of the

practice of uccāra (and nor can I, through the medium of the Internet).

However, in his version of verse 67 (SJ, Feb. 2016) he radically misrepresents the scripture. His poem is unrelated to the meaning of the original verse,

and even contradicts it. Roche thinks that “the verse is pointing to ways of evoking the experience of chills and tingles running up and down your spine,

as in sex, and any thrilling experience.” Nothing could be more opposite to the author’s intended meaning, which is:

The practitioner who stops all the streams of prāṇa-śakti [from flowing out through the senses and orifices] will experience it [enter the central

channel and] slowly rise upward. In time he will experience a sensation [like the crawling] of ants [on his skin]; then supreme pleasure manifests.

|| 67

The verse clearly describes the sometimes strange somatic experiences that come with prolonged meditation and sensory deprivation. The additions I have

made in brackets are not speculative; they supply information commonly found in parallel sources. This is why to translate correctly one needs to have read

the relevant literature, most of which exists only in Sanskrit. In Roche’s poem, the only connection to the original verse is the single word ‘ant’. Nor is

the author of this verse interested in “any thrilling experience” but specifically in a goal only attainable by overcoming the pull of the senses

toward experience.

This article could easily be longer, but perhaps by now the point has been well proven. Let us then consider some implications. What cultural context

enables the kind of appropriation and obfuscation we have been considering?

Śveta Bhairava, Bhaktapur, Nepal

Implications and wider issues: anti-intellectualism and relativism in American culture

Though I don’t have the space to expand much upon it here, it seems to me that Roche’s work exemplifies some disturbing trends in American spiritual

subculture(s) and American culture generally: trends of anti-intellectualism, relativism, and (as I call it) the artifice of individualism. It’s always

been the case that compared to Europe or India, Americans tend to distrust (or at least not particularly respect) experts in intellectual fields. Though

people are careful to go to experts when it concerns the proper functioning of their car or their body, they do not consult them before forming an opinion

on matters of culture or religion. It’s almost as if the general public is unaware that expertise in these fields can equal the level of detail and

sophistication found in the sciences. In the case of religion, however, the reason Americans don’t consult experts in the field is well known: the dominant

paradigm of American religiosity is one of individual experience free of the necessity for priests or clerics. (This paradigm is based in Protestant

Christianity, the dominant religion in early America.) What William James said in 1902 is still true today; that for most Americans, religion constitutes

“the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may

consider the divine.” Yet here’s where this otherwise respectable view goes wrong: many people don’t think they need expert opinion on anything to do with religion, even when the issues are historical or linguistic rather than strictly spiritual. Roche seems to be a prime example

of this phenomenon, but I have seen many more in discussions on social media. The implications of this are considerable. Most Americans don’t understand

anything of the worldview held by people of other religious faiths, from the mainstream Muslims they so easily lump together with the fanatics, to the

Hindus that they either exoticize or ridicule.

The latter part of the William James quote also points us in the direction of a related problem, that of relativism. This is the view that since each

person is entitled to his or her opinion, all opinions are basically equal. Some extend this to the belief that all views of reality are equally valid

(this is what is called relativism). Experts in philosophy have long since shown that relativism is either incoherent and nonsensical or else

masks a kind of nihilism (since all views can be equally valid only if they are all equally false, leading us to the conclusion that nothing is

really true).[26] The popular (though not thought-out) American commitment to relativism has bolstered

distrust of expert opinion, because after all, if everyone’s opinion is equally valid, why would you need experts?

Both anti-intellectualism and relativism are abundantly on display in the modern yoga scene. Students of mine have reported to me the scorn of their fellow

practitioners at the yoga studio; comments like, “Why do you need to study so much? Why don’t you just experience it? Don’t you know yoga is all about the

experience? Get out of your head!” Yet this opinion is at odds with the strong intellectual culture of premodern India, the birthplace of yoga. If the

texts that have survived are anything to go by, many practitioners of days gone by thought very deeply about what they were doing, why they were doing it,

and what views of reality were logically compatible with the spiritual experiences they were having. They didn’t think intellectual cultivation was at odds

with spiritual practice, probably because they understood that the former is necessary for a mature faculty of discernment. As a scholar-practitioner, I

sometimes despair about how wide the gap is between scholarly reflection on these issues and popular lack of the same.

The issues I have outlined perhaps shed some light on why modern American yogis often don’t see the value of critical articles like this one, and even

regard them as mean-spirited. Too often in American yoga, only positive language is approved, and critical discourse is frowned upon, in part because of

the hippie/relativist ethic that “everyone should be allowed to do or think what they like,” with criticism being seen as interference with this sacrosanct

principle. But in reality, carefully considered critical opinion usually arises from love and care and the desire to strengthen and benefit whatever is

being criticized. This is certainly true in the present case.

I well understand that Lorin Roche and most of those in his community have had blissful experiences with the poetry that he has created and will see my

analysis as unnecessary rain on their parade. Of course I have nothing against people enjoying themselves; my concern is whether they are also deluding

themselves. Do they think they have access to the teachings of an ancient Tantric scripture when in fact they don’t? Do they think they have a set of

practices that bring about spiritual awakening and liberation when in fact they don’t? Do they believe that the philosophies of hedonism and yoga are

mutually compatible when in fact they aren’t? I think these are important questions.

Kala Bhairav, Kathmandu, Nepal

Appendix: more translations from the Vijñāna-bhairava-tantra

There is never the slightest separation between Shakti and her Host (i.e. Shiva); thus, because there can be no separation between a quality and that in

which it inheres, the Power (śakti) of the Supreme Being is itself Supreme (parā). || 18

The power of fire to burn cannot be considered as separate from the fire itself. Shakti is only considered separate initially [as a teaching tool], to aid

in [our] entry into the state of insight (jñāna-sattā).* || 19

The nondual meditation of one who enters into the śakti-state will certainly develop into an expression of Shiva-consciousness (śiva-rūpī

). In our way (i.e. the Kaula way), Shiva's shakti is said to be the entryway [into Shiva]. || 20

Just as different directions [of any given space] are known through the light of a lamp or the rays of the sun, in the same way Shiva is known through

Shakti, O beloved. || 21

. . .

Imagine that [kuṇḍalinī] śakti, the subtlest possible form [of prāṇa], as rays of light shining upward from the root [of the

central channel] and peacefully dissolving in the highest center above the crown; [then] intensified awareness arises. || 28

[Feel kundalinī] śakti rising like a streak of lightning from one subtle center (cakra) to the next in succession. When She

reaches the upper[most] center, three fists above the crown, there comes the culmination, the Great Dawn of liberation. || 29

There are twelve [such centers] in sequence; properly associated with twelve vowels (a, ā, etc.). By fixing [awareness] on each one, in successively

coarse, subtle, and supreme [forms], in the end, [you find] God. || 30

Having quickly filled the crown center with that [prānic] energy, [and] having breached [the knot of māyā (above the palate)] with the ‘bridge’ of

concentration between the eyebrows, [and] having made one’s mind free of mental chatter, one ascends to the all-pervasive state (Vyāpinī) in the

[place] above all (i.e. the uppermost center above the crown). || 31

. . .

The concluding verses of the text recap the beginning, and further elaborate on the philosophy of the Vijñāna-bhairava:

The Goddess said: “If, O Lord, this is the true form of Parā, how can there be mantra or its repetition in the [nondual] state you have taught? What would

be visualized, what worshipped and gratified? And who is there to receive offerings?” (vv. 142b-144a)

The revered Bhairava said, “In this [higher way], O doe-eyed one, external procedures are considered coarse (sthūla). Here ‘japa’ is the ever

greater meditative absorption (bhāvanā) into the supreme state; and similarly, here the [‘mantra’] to be repeated is the spontaneous resonance [of

self-awareness], the essence of [all] mantras. As for ‘meditative visualization’ (dhyāna), it is a mind that has become motionless, free of forms,

and supportless, not imagining a deity with a body, eyes, face and so on. Pūjā is likewise not the offering of flowers and so on. A mind made

firm, that through careful attention dissolves into the thought-free ultimate void [of pure awareness]: that is pūjā. . . . Offering the elements,

the senses, and their objects, together with the mind, into the ‘fire’ that is the abode of the Great Void, with consciousness as the ladle: that is homa.

Sacrifice (yāga) is the gratification characterized by [innate] bliss. That which comes from destroying (kṣap) all sins and saving ( tra) all beings is the [true] holy place (kṣetra), i.e. the state of being immersed in the Power of Rudra, the supreme meditation.

Otherwise (i.e., without this inner realization), what worship could there be of that Reality, and whom would it gratify?” (vv. 144b-151)

“In every way, the essence of one’s own Self is simply the awareness of the joy of one’s innate freedom. Immersion into one’s essence-nature is here

proclaimed as the [true] ‘purificatory bath’.” (v. 152)

“Serving Her, remaining on the sacrificial path consisting of great joy, immersed in the power of that Goddess, one attains supreme Bhairava.” (v. 155)

by Christopher (Hareesh) Wallis, Ph.D.

March, 2016

show Christopher (Hareesh) Wallis, Ph.D.'s Bio

About Christopher (Hareesh) Wallis, Ph.D.

Christopher (Hareesh) Wallis was introduced to Indian spirituality at the age of six and initiated into the practice of meditation and yoga at sixteen. His

degrees include a B.A. in Religion from the University of Rochester, an M.A. in Sanskrit from U.C. Berkeley, and an M.Phil. in Classical Indian Religions

from the University of Oxford. He also pursued graduate work at U.C. Santa Barbara, and completed his Ph.D. at U.C. Berkeley on the traditions of Tantrik

Shaivism. He received traditional education at yoga āshrams in upstate New York and India in meditation, kirtan, mantra-science, asana, karma-yoga, and

more. He currently teaches meditation, yoga darshana (philosophy), Sanskrit, chanting, and offers spiritual counseling.

Hareesh is the Founder and Head Faculty of The Mattamayura Institute. His teachers, mentors, and gurus, in chronological order, include: Swami Muktananda;

Gurumayi Chidvilāsānanda (diksha-guru and mula-guru), Paul Muller-Ortega (Shaiva Tantra and Classical Yoga); Douglas Brooks (Shakta Tantra); Alexis

Sanderson (Shaiva and Shakta Tantra and Sanskrit); Marshall Rosenberg (Nonviolent Communication); Somadeva Vasudeva (Shaiva Tantra), Dharmabhodi Sarasvati

(Tantrik Yoga); and Adyashanti (Meditation). Hareesh is author of Tantra Illuminated: The Philosophy, History, and Practice of a Timeless Tradition.

show other content from Christopher Wallis

Other Content by Christopher Wallis

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.