Pauranik vaav, Bapunagar

INTRODUCTION

‘Stepwells of Ahmedabad - a conversation on water and heritage’ is a collaborative effort of a diverse group of researchers, practitioners, young graduates,

students and concerned citizens to bring to light aspects of this recurring typology of water structures that are dispersed across the semi-arid and arid

landscape of Western India. The first edition of this travelling exhibition was held at the Kanoria Centre for Arts in Ahmedabad from the 22ndto

29thMarch 2016. This endeavor began with the documentation of sixteen stepwells in and around the city of Ahmedabad, hoping to garner interest

and raise discussions not only about the architectural merit of the structures themselves, but also larger issues of water, settlement patterns and social

relationships to which they are connected. Within this framework, a conversation on their present condition, value and the issues of heritage in the

context of the city was initiated.

The exhibition "Stepwells of Ahmedabad" held at Kanoria centre for Arts

Along with the exhibition, active citizens of the city who are involved at a professional level with issues of water and heritage were invited to share

their experiences with the audience of the exhibition every evening. The speakers included, Ashoke Chatterjee ( Former executive director NID and

participant in the World Water Forum), Mansi Bal (Research Entrepreneur and educationist), Jitu Mishra (Archaoelogist) and Prof. R. Vasavada ( Former Head

at the Centre for Conservation studies, CEPT University).

The following stepwells were documented as a part of this endeavour : Rudabai ni Vaav, (Adalaj), Bai Harir ni Vaav (Asarva), Amritavarshini Vaav

(Panchkuva), Jethabhai ni Vaav (Isanpur), Vaav at Vadaj, Maata bhavani ni vaav (Asarva), Ashapura maata ni vaav (Bapunagar), Gandharva vaav (Saraspur),

Khodiyar maata ni vaav (Bapunagar), Ambe maata ni Vaav (Malav Talav), Sindhvai maata ni Vaav (CTM crossroads), Khodiyar maata ni vaav (Vasna), Vaav at

Bhadaj, Vaav (Doshiwada ni Pol), "Pauranik" Vaav ( Bapunagar), Kali maata ni vaav ( Bapunagar).

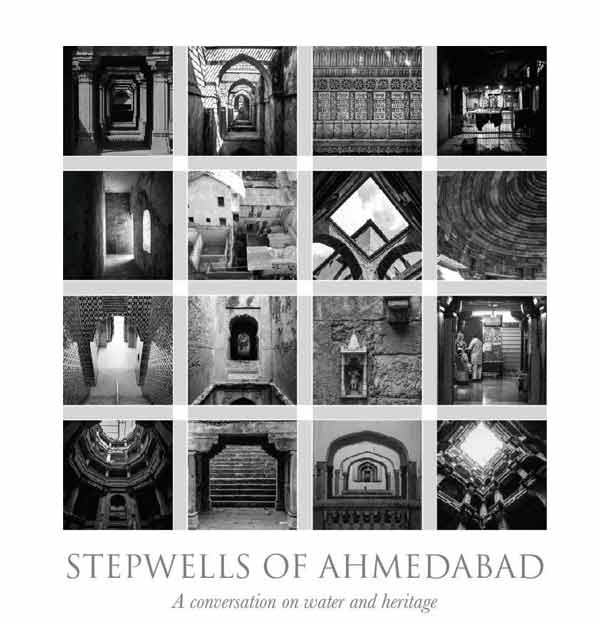

A photo collage of the sixteen stepwells that were documented

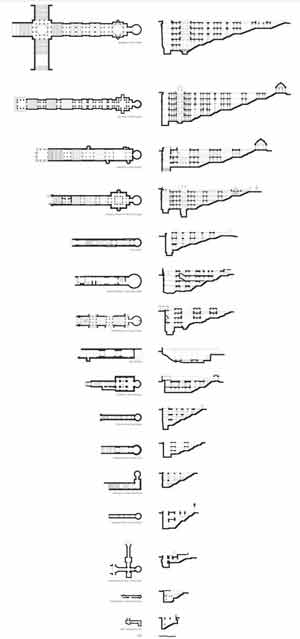

Comparative plans and sections of the 16 stepwells

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SURFACE WATER, GROUND WATER AND SETTLEMENT

The city of Ahmedabad situates itself in the gently undulating plains of North Gujarat. In this semi-arid landscape, water is of paramount importance and

its collection, preservation and use deeply influences the patterns of human settlement. From the smallest village to the largest city, one can see a

consistent pattern in the relationship between where water gets collected in the depressions of the land, forming small lakes and ponds called ‘talavadi’, and the higher ground or mound (‘tekro’) which is inhabited by settlements. This relationship between the shape of the land

and the settlement often affects the organisation and the character of the built form. Generally, a temple marking the center of the settlement occupies

the highest point of the mound and the streets follow the pattern of water flow as it drains away from this high ground into the surrounding agricultural

areas that support the settlement. These manmade lines connect with the natural flow to mark the movement of man and water through the landscape.

Typically, the ‘talavadi’ that is adjacent to the settlement is located outside it for reasons of health and hygiene. This domain of stagnant

surface water is often associated with deities, gods and goddesses that are symbolically kept outside the settlement, and the cremation areas are placed on

the edges of such water bodies. Though essential for agriculture, animal husbandry and rearing and human washing, this water is not seen appropriate for

drinking.

Drinking water is almost always from a ground water source - a dug well, or in the cases documented here, a stepwell (‘vaav’). The position of the

stepwell is often between the settlement and the ‘talavadi’. In the present context, observations show that where the ‘talavadi’ still

holds water, the well too is alive. However where the ‘talavadi’ has been filled in, or its sources blocked, the well too has dried out,

suggesting a relationship between the surface water of the ‘talavadi’ and the ground water of the stepwell. One might conjecture that through

ideas of purity and hygiene encoded in traditional social practices, it was ensured that surface water must percolate and be filtered by the earth before

it’s seen to be fit for drinking. The ‘talavadi’ and the ‘vaav’ are both essential to the settlement and bind it to both the surface and

the depth of the earth.

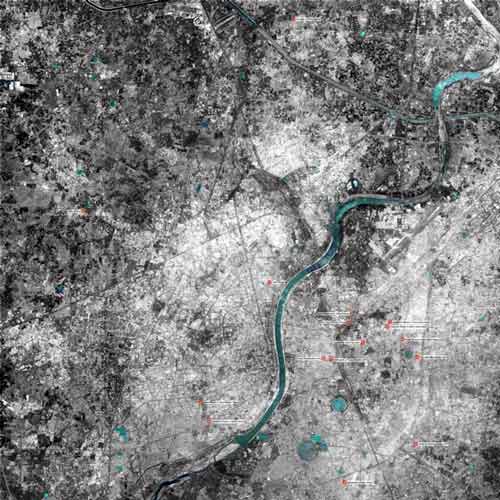

An urban map of Ahmedabad showing the water bodies in blue

and the location of the 16 stepwells in red

GENDER AND PATRONAGE

"It is now also come to light that many of the stepwells were built by women – queens, wives of affluent traders, ordinary women and servant girls. Not

only did women commission stepwells as patrons, they also frequently served as an inspiration. Stepwells are often built in honor of a virtuous wife, a

benevolent mother, a beloved mistress or a local goddess. The articulation and embellishment inside these structures are often expressive of this

feminine character creating a delicate spatial filigree."

(Purnima Mehta-Bhatt; Her Space, Her Story)

For many cultures around the world, the earth is feminine. The dark, deep, cave-like realm of the underground and the crop-rich abundance of its surface

are some of its recurrent symbolic aspects. In a semi-arid landscape, there is a strong, literal and symbolic association of water with fertility and

fertility with abundance. Structures constructed for water embody this latent femininity, none more so than the well and the stepwell. The gift of water for

public use was considered to be one of the greatest acts of charity and brought great merit to the patron. Many of these stepwells were commissioned by

women such as the Rudabai ni Vaav At Adalaj on the outskirts of Ahmedabad and the Bai Harir ni Vaav, which is situated in the Asarva area of Ahmedabad.

However, it was the real everyday routines and rituals that linked women directly to the stepwell. Their daily fetching of water, washing and cleaning is a

common sight even today in many villages of this region. We can imagine that it was at the stepwells where women could socialise freely away from the gaze of

men in the village squares ('chowk') or the the royal court (‘darbar'). This is where they would talk and gossip, exchange household

stories, engage in politics and seek the companionship of other women. They provided a socially legitimate opportunity for women to move out of the

domestic realm into the public domain at a time when this possibility was denied to women for the larger part.

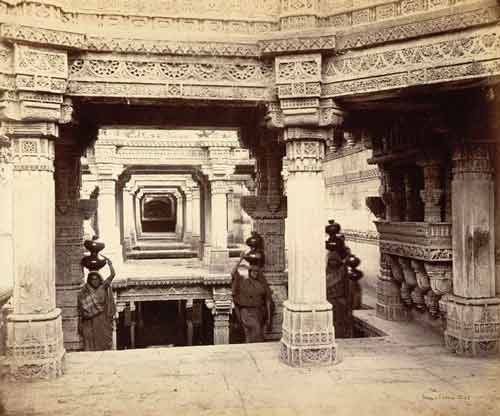

Photo by Colin Murray, 1872 of women fetching water at the Rudabainivaav, Adalaj.

Source: British Library Archives

Even today, stepwells are often referred to as "women's spaces". In many of the stepwells, today shrines have sprung up or in other cases the stepwells

have been converted into temples. All these shrines and temples are invariably dedicated to some incarnation of the Mother Goddess, referred to as "Maata"

in Gujarati. A few of these Goddesses are at the heart of a cult exclusive to women. In villages and the countryside, this cult continues to flourish even

today. These local goddesses are worshiped and their blessings invoked by women for protection, health and well being.

Idols of the Goddess Khodiyar Maata installed at one of the stepwells.

INHABITATION AND THE LIVING BUILDING

The present day condition of the sixteen stepwells documented in Ahmedabad vary greatly. The best-known stepwells, such as Rudabai’ stepwell at Adalaj and

Bai Harir’ stepwell at Asarva are maintained as heritage structures by government agencies and attract a large amount of tourist interest.

Rudabai niVaav, Adalaj, 2016

Others however, are used in a different way. The Mata Bhavani stepwell at Asarva now has a community dwelling around it. A Mata (Goddess) deity has been

installed and the stepwell now functions as a temple for the surrounding communities. Small shrines have been added and minor alterations made in the

service of this function.

Mata bhavani ni Vaav, Asarwa, Ahmedabad.

In the Ashapura maata ni Vaav, the first pavilion has been converted into a shrine dedicated to the Goddess Ashapura and the informal settlement has grown

along the edge of the stepwell on the either side.

Ashapura maata ni Vaav, Bapunagar

On the other hand, at the Gandharva Vaav in Saraspur, substantial changes made with the well shaft having been filled in and a slab covering it. The

remaining structure is used as a small Goddess Kali shrine.

Gandharva Vaav, Saraspur

At the Ambe Mata ni Vaav, Malav Talaav, the original levels have been flattened with almost no trace of the original structure. The insides are profusely

decorated with mirror and tile work.

Ambe Maata ni Vaav, Maalav Talaav.

In all these cases, the inhabitation of the buildings by the immediate community has ensured that these structures still find themselves as active spaces

within the urban fabric. The buildings belong to the temple trust. This raises questions about the abstract manner in which the idea of ‘heritage’ is

constructed and discussed, its emphasis on the notion of ‘original’ form and use of buildings and the more difficult question of, ‘Whose heritage is it?’

Apart from these inhabited buildings, the wells that were documented were the ones at Bhadaj, Doshiwada ni Pol and the Khodiyar Mata vav at Vasna. They are

unused, dilapidated and uncared for.

The dilapidated stepwell at Bhadaj

HERITAGE

Historical events or processes with a special meaning to a group of people constitute heritage. In many contexts, both meaning and the group have largely

been stable, consistent and seen to be unchanging. In the Indian contexts however, there is a dynamic relationship between social groups and their place.

Meaning is more fluid in time, resulting in shifting notions of identity and belonging. Often, the ideas of ‘heritage’ are abstract, one learns as an

initiation in order to be part of a social group. We are schooled to consider structures like step wells to be our heritage. This heritage is necessarily

controlled and maintained by institutionalized public processes. In this system, the greatest efforts are made to maintain, restore and preserve the

building in keeping with the idea of their ‘original’ condition. The inhabited stepwells of Ahmedabad throw up another model for the manner in which

‘heritage’ is engaged with. These structures are not kept in their ‘original’ condition. They are occupied, used, and altered to be integrated into the

daily lives and routines of people. The people for whom these structures have meaning are participators. They are constantly engaged in the rituals that

tie these building to a larger social context. It is their inhabitation that makes these buildings ‘theirs’.