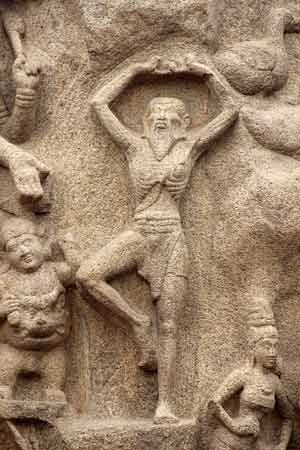

Arjunas Penance Descent of the Ganges, Mahabalipuram

Originally published in Journal of Vaiṣṇava Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2, Spring 2001, pp. 23-31

In the first chapter of the Bhagavad Gītā, entitled Arjuna-visāda-yoga, or “the Yoga of Arjuna’s Crisis,” Arjuna

collapses, unwilling and unable to continue into battle. In this dramatic moment Arjuna becomes every person who has been paralyzed by an ethical dilemma,

unwilling and unable to take decisive action before sorting through one’s circumstance. In the words of Antonio deNicolas, “Arjuna’s problem would have no

meaning for us unless we are able to get inside his bag of skin.”[1] In this essay, I

will explore the arguments that Arjuna employs against the notion that he must fight, exploring their possible validity and the ultimate reasons for their

rejection. I will also return to some reflections on deNicolas’ statement regarding the universality of Arjuna’s dilemma and the possible role of dramatic

tragedy in the promotion of nonviolence and pacifism.

In twenty years of teaching the Bhagavad Gītā, students have from time to time argued in class that the weak Arjuna was right in

protesting the battle, that he should not go to war, that the family structure should have been protected, that Krishna was full of bad advice. Mahesh

Kumar Sharan has commented that “because people do not realize the circumstances under which the Gītā was spoken, and take it as a book of

isolated teachings, that they commit the grievous mistake of saying that it inculcates manslaughter.” [2] Sharan indicates that one must approach the Bhagavad Gītā with a

full understanding of the overall plot and structure of the Mahābhārata. In my teaching of the Gītā, I have

been consistently quite careful to explain the context of the events leading up to the war and try also to convey the concept that in fact Arjuna has to

kill or be killed; even if he refuses to fight, his death alone will not prevent the battle. However, some students remain quite obstinate in their

insistence that Arjuna’s arguments are correct, that it would have been better for him to sacrifice his own life to save others. [3] However, the students do not seem to notice that this is not Arjuna’s argument.

Rather than appealing to a notion of self-sacrifice, Arjuna offers two reasons for his retreat: that relatives should not be killed and that women’s purity

must be upheld to preserve the family structure (varṇa). In the essay that follows, these positions will be examined and it will be suggested that

each of Arjuna’s cases ultimately rings hollow, even to himself.

Arjuna's Penance, Mahabalipuram

To begin this exploration, we need first to look at the content of Arjuna’s protest. He presents his argument against killing his kinfolk as follows, in

verses I:30-37:

Gandiva (Arjuna’s bow) fall from (my) hand,

My skin burns,

I am unable to remain as I am,

And my mind seems to ramble.

I perceive inauspicious omens,

O Krishna,

And I foresee misfortune

In destroying my own people in battle.

I do not desire victory, Krishna,

Nor kingship nor pleasures

What is kingship to us, Krishna?

What are enjoyments, even life?

Those for whose sake we desire

Kingship, enjoyments, and pleasures,

They are arrayed here in battle,

Abandoning their lives and riches.

Teachers, fathers, sons

And also grandfathers,

Maternal uncles, fathers-in-law, grandsons,

Brothers-in-law, and other kinsmen.

I do not desire to kill

Them who are bent on killing, Krishna,

Even for the sovereignty of the three worlds.

How much less then for the earth?

What joy would it be for us

To strike down the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra, O Krishna?

Evil thus would cling to us,

Having killed these aggressors.

Therefore we are not justified in killing

The sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra, our own kinsmen.

How, having killed our own people,

Could we be happy, Krishna?[4]

L'Ascèse-d'Arjuna (Mahabalipuram)

Arjuna balks at killing “teachers, fathers, sons, maternal uncles, fathers-in-law, grandsons, brothers-in-law, and other kinsmen” and then goes on to

proclaim “I do not desire to kill them who are bent on killing” (I:34-35). He specifically states that he does not want to kill the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra.

The first part of this soliloquy articulates Arjuna’s reluctance to put the lives of his own brothers and maternal relatives at risk. This would be noble

of Arjuna and understandable in light of any battle in any war. However, when he balks at raising his weapons as the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra, he in fact has

forgotten the numerous slights and insults suffered by himself and his brothers.

When teaching the Bhagavad Gītā, I am quite careful to introduce the text by providing the context of the battle. The sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra hated

the sons of Pāṇḍu since childhood. The sons of Pāṇḍu were legitimate heirs to the throne; the name Dhṛtarāṣṭra means “he who holds the throne,” indicating

that he was serving as regent for his nephew Yudhiṣṭhira, a point agreed upon shortly following the death of Pāṇḍu.[5] Yet Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s eldest son Duryodhana wants to seize the throne. He attempts to

burn his cousins alive in a house made of lacquer. The Pāṇḍavas then go into hiding, during which time they develop important alliances, most notably with

King Drupada (whose daughter Draupadī becomes their joint wife) and their cousin Krishna. When they return from this self-imposed exile, the Pāṇḍavas agree

to accept a piece of the kingdom, and they build the city Indraprastha. They declare independence from their home city of Hāstinapura, which they have left

in the hands of Duryodhana. However, jealousy and fear stalk Duryodhana. He challenges Yudhiṣṭhira to a dice match. Yudhiṣṭhira loses everything, including

the beloved Draupadī. She, having been waged after Yudhiṣṭhira lost his own freedom, contests the result. Dhṛtarāṣṭra abrogates the game but Yudhiṣṭhira

accepts one final challenge. He loses, and he and his brothers and wife are sentenced to twelve years of forest banishment and one year in hiding. One

important point: Duryodhana had cheated, using his mother’s brother Śakuni to rig the dice games. At the end of the thirteenth year, the five Pāṇḍava

brothers willingly accept a compromise of moving to five small villages. Duryodhana refuses and prepares for the battle that Arjuna now faces.

In instance after instance, Duryodhana violated agreements and attempted to end the lives of his hated cousins. The Pāṇḍavas did not attempt to kill the

sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra; in three instances, they retreated, first to the kingdom of Drupada, then to the city of Indraprastha, and finally in the thirteen

year exile. Despite this history of rift between the cousins and the repeated threats to the lives of the Pāṇḍavas, Arjuna, in this moment of weakness,

seems willing to lay down his weapons in order not to kill relatives that hate him. Arjuna does not at all seem to recall the reasons for the war and does

not even once mention the hatred he has felt repeatedly from Duryodhana and his other cousins, nor does he mention the slight to Draupadī that so incurred

her wrath. Hence, when he shows reluctance to fight, it seems to stem from a lack of resolve rather than any admission that he and his brothers deserve to

die; they have done no wrong, other than to survive and succeed.

The second argument presented by Arjuna concerns the mixture of caste and the threat to the purity of women:

Even if those whose thoughts

Are overpowered by greed

Do not perceive the wrong caused

by the destruction of the family

(kulakṣayakṛtam doṣaṁ)

And the crime of treachery to friends.

Why should we not know enough

To turn back from this evil,

Through discernment of the wrong caused

By the destruction of the family, O Krishna?

(kulakṣayakṛtam doṣaṁ).

In the destruction of the family,

The ancient family laws vanish;

When the laws have perished,

Lawlessness overpowers the entire family also.

Because of the ascendancy of lawlessness, Krishna,

The family women are corrupted;

When women are corrupted, O Krishna,

The intermixture of caste is born.

(adharmādhibhavāt kṛṣṇa>

praduṣyanti kulastriyaḥ

strīṣu duṣṭāsu vārṣṇeya

jāyate varṇasaṁkaraḥ)

Intermixture bring to hell

The family destroyers and the family, too;

The ancestors of these indeed fall,

Deprived of offerings of rice and water.

By these wrongs of the family destroyers,

Producing intermixture of caste,

Caste duties are abolished,

And eternal family laws also.

(doṣair etaiḥ kulaghnānāṁ

varṇasaṁkarakārakaiḥ

utsādyante jātidharmāḥ

kuladharmāś ca śāśvatāḥ)

Men whose family have been obliterated,

O Krishna,

Dwell infinitely in hell,

Thus we have heard repeatedly.

Ah! Alas! We are resolved

To do a great evil,

Which is to be intent on killing our own people

Through greed for royal pleasures.

If the armed sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra

Should kill me in battle

While I was unresisting and unarmed,

This would be a greater happiness for me.

Thus having spoken on the battlefield,

Arjuna sat down upon the seat of the chariot,

Throwing down both arrow and bow,

With a heart overcome by sorrow

(ṣokasaṁvignamānasaḥ).[6]

Arjuna's Penance, Mahabalipuram

In this part of his discourse, Arjuna speaks of the potential threat to the women of his family if the war takes place. He asserts the need to prevent the

mixture of castes by protecting the integrity of the women of the family. However, as with the prior argument, his memory seems quite clouded, particularly

when he refers to “ancient family laws.”

The women of the Mahābhārata in Arjuna’s lineage demonstrate a fascinating combination of noble, lowly, and godly

births and family backgrounds. The story begins with Arjuna’s step great grandmother, Ganga, a river goddess “on loan” to Arjuna’s great grandfather,

Santanu. Arjuna’s paternal great grandmother, Satyavati, was a product of a noble king, Vasu who, inspired by the sight of a beautiful woman, spurts forth

seed that is consumed by a fish. Satyavati is raised in a family of fisher folk. Arjuna’s great grandfather, Santanu, is a warrior and king; his great

grandmother was a ferry operator, a businesswoman reared by the fisher family. His presumed paternal grandfather (through the line of Pāṇḍu) was a Brahman,

the son of the fisher woman. His grandmother was a princess won by his step grandfather, Bhiṣma. His presumed father was King Pāṇḍu, who reigned because

his elder brother was born blind. His actual mother, Kuntī, was of a royal lineage but, due to the antelope’s curse placed upon Pāṇḍu, unable to bear him a

child. Hence, she enacted a power taught to her by the sun god, enabling her to bear children by different gods of her choosing. Hence, Kuntī bore children

by multiple gods: the Sun (Sūrya), Righteousness (Dharma), the War God (Indra, Arjuna’s father), and the Wind God (Vāyu).

Arjuna’s five brothers likewise share complicated births. His older hidden brother, Karṇa was born of the sun. Yudhiṣṭhira was born of Dharma and Bhīma was

born of Vāyu, Arjuna’s step-half brothers, Nakula and Sahadeva, were born of the solar deity Aśvin twins when Kuntī taught her co-wife Mādrī how to invoke

the power taught to her by the Sun.

In terms of ancestry, Arjuna does not have the sort of clear and distinct history that makes him a credible advocate for “nonmixing of castes.” His

predecessors include a goddess, a fish, a fisherwoman, a Brahman, queen, and a god. Furthermore, his own marital history is also complicated. His first

wife, Draupadī was won in a contest after the Pāṇḍavas escaped the first two murder attempts by Duryodhana. But due to famous words uttered by his mother,

unaware of Arjuna’s feat, Draupadī was to be shared equally by all five brothers, an unusual marriage situation in any culture. His second wife, Subhadrā,

was his cousin and sister of Krishna. Through their relationship, the lineage continues, but only when the gods rescue the embryo of Arjuna’s unborn

grandson.

Above all else, this tangled web of relations, human and superhuman, underscores the mystery of birth and the ever-present possibility that those who one

assumes to be one’s ancestors are not one’s true progenitors. Did the fisherman really find Satyavati in the belly of a fish? Did Śantanu really have a

relationship with the river Gāṅgā? Was the Brahman Vyāsa, also known as Kṛṣṇa-Dvaipāyana (who slept with Satyavati’s daughters-in-law) really her son? Did

Kuntī really bear children by four different gods? If the answer is yes, then certainly there has been even more than a mixture of castes. If the answer is

no, then a great deal of deception and story telling has transpired.

Why would these fantastic tales of godly births be woven into the epic? On the one hand, this literary device indicates a continuity between the human and

heavenly realms. Gods and goddesses take human shape and help form the bodies and personal qualities of their issue. But they also serve as a convenient

fiction to further the plot of the story and add credibility to the claims to kingship put forth by the inheritors of the kingdom. It also perhaps helps to

dean up questionable activities on the part of the main characters. A mysterious child can be legitimated by attributing its appearance to divine

intervention.

In the final analysis, these interweaving stories that blur the distinction between gods and humans, brahmans and kṣatriyas, kings and fisherfolk, work

against Arjuna’s argument that he must spare the lives of his hated kinfolk in order to protect the sanctity of women. As he learns later in the battle,

his own mother gave birth to a child before her marriage to Pāṇḍu. His own brother was, in a sense, his greatest enemy.

The appeal of the Mahābhārata lies partly in its portrayal of the human dilemma in all its ambiguity. It speaks to the

human condition in the starkest of terms. The first chapter, in particular, places Arjuna “in the midst of his own authentic reality: despair, anxiety,

inaction.”[7] People, even acknowledged divine presences such as Krishna, must cover

and conceal themselves and advise others to violate dharma in order to protect dharma. Arjuna moves from an innocent and even naïve view of dharma to the

realm of experience in the course of the Bhagavad Gītā. He sees the ultimate crushing of all his enemies in the mouth of Krishna. He sees

that the higher governing principles are not easy to discern, that the decision making process in times of trouble must come not from rationality but a

higher source of inspiration. Krishna personifies that inspiration but, in the words of Antonio T. de Nicolas, Krishna serves as the occasion for Arjuna’s

own embrace of his own circumstances. And, ultimately, sadly, late in the Mahābhārata, even Arjuna forgets what he has

learned, and suffers for a time in hell because he had fought treacherously against Karṇa. Even the heroic protagonists must suffer the consequences of

their bad deeds.

This brings me to the larger issue of why my students protest the seemingly pro-war message of the Bhagavad Gītā. Gandhi himself

struggled with this and, like Abhinavagupta before him,[8] decided that the Gītā provides an allegory for the inner struggle. He wrote that

to me the Mahābhārata is a profoundly religious book, largely allegorical, in no way meant to be a historical record.

It is the description of the eternal duel going on within ourselves.[9]

Gandhi also made clear that, to him, the war was not glorified but represented a great tragedy:

The author of the Mahābhārata has not established the necessity of physical warfare; on the contrary he has proved its

futility. He has made the victors shed tears of sorrow and repentence, and has left them nothing but a legacy of miseries. [10]

Particularly in light of the approach taken by Peter Brook’s rendering of the epic, one clearly sees that Arjuna and his immediate family pay dearly for

their participation in the war. Ruth Cecily Katz summarizes the moral ambiguity succinctly when she writes that “the warfare itself is ambiguous in that,

besides being forced to fight against people who are legally and morally entitled to respect, the Pāṇḍavas are able to win only by means of trickery and

deceit.”[11] Vyāsa does not avoid or deny the tragic aspects of his tale. Because of

greed, obstinancy, and pride, the war rages forth, sowing a bed of unavoidable sorrows. [12] Rather than interpreting the Gītā as a moral treatise on the glories of

war, I, like Gandhi, would prefer to see it as a literary testament to the sometimes inevitably tragic aspects of the human condition.

Arjuna, as a tragic heroic figure, represents the challenge of making difficult moral decisions. The human story often includes mysteries that do not lend

themselves to easy resolution. In such circumstances, Hinduism offers a template in the person of Arjuna for finding “one’s radical orientation beyond the

dictations of controlled situations and through these controlled situations.”[13] A

literary tale can bring our human horizon beyond the strictly rational modality into a higher level of understanding, appreciation, and insight. In this,

and in Arjuna’s fulfillment of his destiny as a literary character, we are led to greater human freedom.