Ladakhi Woman wearing Perak (cobra-shaped ceremonial

headdress), by Peter Bos. Photograph. 2015

It is a choice to remember life in beautiful ways. Dance is an art made of life itself. The human body as medium contains within it every aspect of

humanity. The body by becoming a symbol of meaning can probe deep levels of experience, and speak universally. It takes on style, shape, and decoration; it

carries tradition, contemporary interpretation, and the ability to transform consciousness.

When dance begins to disappear, to die out, something of the life of a culture dies too: its communal ritual expression, its relation to the environment,

its upholding of spiritual values. How do the values and qualities of disappearing dance come to be saved for future transmission and ongoing

understanding?

The organization I direct, Core of Culture (CoC), looks at actual dance practice, and works with locals to bolster it. CoC makes scientific documentation

of ancient dances, showing their structure and choreography. We seek pristine conditions. The apex of that work is a 500-hour archive of Bhutanese Buddhist

dance, maintained by the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.*

Ladakhi Woman Adjusting her Perak (cobra-shaped ceremonial

headdress)by Peter Bos. Photograph. 2015

In years past, explorers took photographs and made films that included dance. They may not have been dance or film specialists, but they recognized the

significance of dance to a culture and often sought to record it, showing the amplitude of its social and religious context, and often, to their eyes, its

oddity.

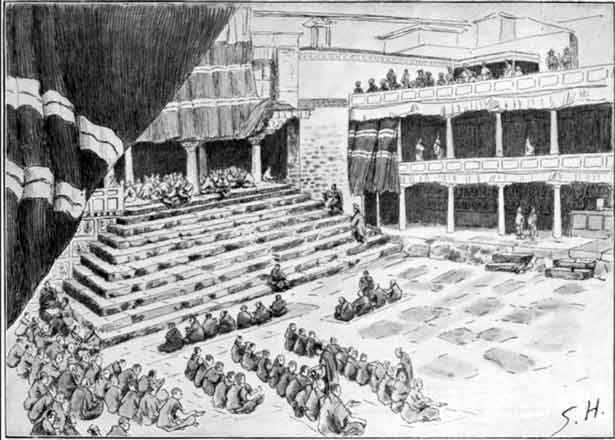

The following three images are by the celebrated Swedish adventurer Sven Hedin (1865–1952), who made four expeditions into Central Asia around the turn of

the last century. He was a considerable artist and a reliable photographer. The first, a drawing, shows his keen interest in context and accuracy. It

depicts the array of monks having tea in the ceremonial courtyard of Tashilhunpo Monastery.

Lamas drinking Tea in the Court of Ceremonies in Tashi-Lunpo, by Sven Hedin. Pencil

drawing. After Trans-Himalaya, Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, Vol. 1, 1909,

The Macmillan Company, New York, fig. 143

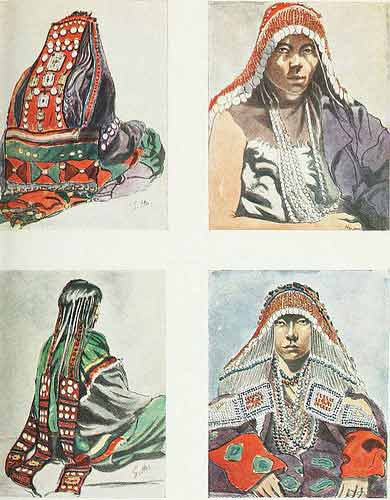

The second, a photograph, shows a group of Ladakhi women from the village of Chusut performing dances in a stony courtyard. The clothing, setting, and

movement are all true in an anthropological sense. It is ethnographic documentation. In the third, a set of four women, Hedin chooses to remove them from

the context of place and ceremony and to record aspects of the adorned women, isolated, specific to a realistic watercolor sketch. The women and their

finery are appreciated entirely alone, for themselves as objects of study.

Dancing women in Chusut, by Sven Hedin. Photograph. After Trans-Himalaya,

Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, Vol. 2, 1909, The Macmillan Company, New York, fig. 282

Ceremonial costumes and ornaments of Tibetan women of

Kyangrang, by Sven Hedin. Watercolor sketch. After

Trans-Himalaya, Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, Vol. 2,

1909, The Macmillan Company, New York, fig. 362

More recently, Dutch explorer and photographer Peter Bos has made a mission for himself in midlife, to leave his occupation as a businessman and travel to

places where culture is disappearing. Peter Bos is an artist. His photography is being shown from 21 March at the National Museum of Humankind in Bhopal,

India. A book of his photographs, Last of the Tattooed Headhunters: The Konyaks, with text by Phejin Konyak, is being optioned by several

publishers. Bos sees beauty in what he photographs, a kind of eternal presence transcending time. More than that, at the same time, the photographs—of

single people in isolation—express fragility. Transmission cannot happen with one person.

What Bos preserves is not choreographic or anthropological context. Bos preserves what is sublime in its peculiarity; what appears to be from a former

time, standing out with nobility in our own. In this he is heir to the exquisite style of American ethnographer Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952), whose

photographs of North American first peoples remain some of the most compelling documentation of a great civilization.

These photographs are a type of studio portraiture, raising every problematic issue with both studio styled artists and the genre of portraiture, in the

face of a different culture. (Full disclosure: I much admire studio artists and portraiture.) Bos’s “disappearing portraits” are works of great beauty, and

for that alone, they will last.

Young Ladakhi Woman in Ceremonial Dress, by Peter Bos. Photograph. 2015.

This is the attire worn to Buddhist ceremonies, when greeting high lamas, and

for dancing. It is similar to that in the Hedin photograph above, where the

Ladakhi women are also wearing capes.

Bos attains some comprehension of performance by also photographing the handsome Brogpa hill people, a tribe, neither Ladakhi nor Kashmiri, reputed to be

descended from Aryans. The Brogpa speak their own language. They are known for their incredible jewelry and extraordinary floral headdresses.

The photograph below shows their ceremonial attire for Harvest Festival dances as well as for dances they perform at Buddhist Cham festivals, such as at

Lamayuru Monastery in Ladakh. The Brogpa walk many miles over the high Fotu-la Pass in order to attend. A weeping transvestite oracle in a trance

accompanies them and stays the entire three days of the Buddhist Cham ritual. The Brogpa dance on the final day. This integration of local customs around

the Buddhist celebrations is common, indeed a characteristic of Buddhist festivals, ancient and modern.

Brogpa Woman in Ceremonial Dress,

by Peter Bos. Photograph.

2015

Memory becomes further abstracted and objectified in the amazing exhibition of jewelry from the Himalaya and Central Asia, Vanishing Beauty, at

the Art Institute of Chicago from 19 June this year. The exhibition is curated by one of the world’s foremost specialists in Asian art, Madhuvanti Ghose,

Alsdorf Associate Curator of Indian, Southeast Asian, Himalayan, and Islamic Art at the Art Institute. Her broad and detailed knowledge finds apt

engagement in the wide-ranging geographical extent of the collection. Similarly wide-ranging are the functions the items of jewelry carry out.

Collector Barbara Kipper is a rare bird. She has traveled to India more than ten times and Africa more than twenty times, and made an overland expedition

to Afghanistan from London in 1968. Mrs. Kipper has visited nearly every Buddhist culture in Asia. She is also a devoted patron of classical ballet, and

knows dancing very well.

Mrs. Kipper brings two qualities that may or may not arise on an expeditionary trip: a collector’s eye and discriminating taste. Her collection of

Himalayan and Central Asian jewelry is among the very best and largest in the world.

She is giving part of this collection to the Art Institute of Chicago in order to fulfill her sense of cultural duty by finding a home for these “orphaned”

pieces, where their qualities can be admired and understood, even as the silversmiths and Oracles are dying out. Many pieces of jewelry in her collection

are intended for dance performances, sacred, social, and martial. The exhibition will show pieces of jewelry such as those seen in the photographs here of

Ladakhi and Brogpa people by Peter Bos.

What secrets can jewelry reveal? What ongoing power does the object have for citizens of the world for whom the religion and the ritual are remote, and the

dance steps inconceivable? As a study in contrasts, consider the Newar ritual crown from the Kipper collection along with a photograph of a Tantric

priest-dancer wearing a similar crown. Both illuminate: the dance with a sense of rarity; the museum object with an echo of impending loss. Consider the

jewelry in the photographs by Peter Bos . . . with no women to wear it, no dance to perform.

Tantric priest’s crown. Nepal, Kathmandu Valley, late 18th

century, gilt copper and copper with pigments. Copyright the Art

Institute of Chicago

Newar Tantric Buddhist Priest Prajwal Vajracharya as Vajrayogini, London, 2009,

by Jonathan Greet. Photograph. From Core of Culture

Buddhist Oracles are dancers in a trance, the dance performed by selected monks and sometimes, by high lamas. They wield swords, cut their tongues, and run

rapidly along the edge of the monastery roof wearing a blindfold. They show their power; they make prophecy based on their performed experience. One

powerful object in the Kipper collection is an Oracle’s breastplate, a mirror of the Mind. Let’s look into it.

Oracle mirror (T. melong). Tibet, Ü-Tsang Province, Lhasa, 19th century,

gilt-copper

repoussé and iron inlaid with turquoise, pearls, and crystals.

The Art Institute of

Chicago.

Who was that Oracle? What was his dance like? How did he get into a trance? How are Oracles selected? Mrs. Kipper’s idea in giving her collection to the

public through museums is that these objects—isolated, abstracted, and ensconced in the aesthetic appreciation of beauty—can become doorways, touchstones,

beginnings of a way to go back, to make whole, to complete ourselves with the exploration of disappearing human excellence, what civilizational memory

manages to hold. The context of beauty for our memories is one of respect, and signals another vessel for the transmission of what remains.

*

The New York Public Library Digital Collections: Bhutan Dance Project, Core of Culture

See more

Core of Culture

Website of Peter Bos

This column is dedicated to the beautiful memory of my father, William Houseal.