Theoretical Orientations:

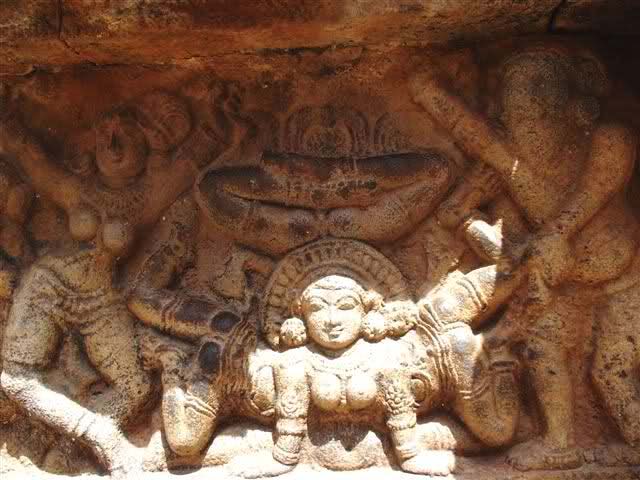

Reading Culture as Embodied Tantric Text

In her work on Vodoun dance traditions Yvonne Daniels articulates a hermeneutics of the danced-body:

Embodied knowledge - that is, knowledge found within the body, within the dancing and drumming body - is rich and viable and should be referenced [by

the scholar] among other kinds of knowledge. In performance . . . [dance] practitioners reveal and reverence history, philosophy, religion, physiology,

psychology, botany, and mathematics in addition to music and dance. These disciplines are among what the body articulates as it grows in spiritual

practice over a lifetime.

(Daniels 2005, 5)

Echoing these sentiments, Gill argues that it is through dance that the aporias inherent in philosophical discourse find their resolution (Gill

2012). By embodying what the dancer is not, the other, by becoming the sign of that ‘other’ the dancer is at once herself and what she is not, by

means of the embodied discourse of dance. In this way, dance, claims Gill, creates the possibility for the impossible.

In this essay I explore the connections between the temple-originated dance traditions of Andhra Pradesh, the hermeneutics of rasa articulated in

both Tantric and alamkara contexts, and the reflections on the danced-body by contemporary exponents of dance. This presentation reflects

preliminary work on a larger book project on the embodied mysticism in Indian arts. In that work I seek to adopt Timalsina’s challenge for an application

of a Tantric hermeneutics to Indian culture, an approach that employs the interpretive logic of Tantra via a creative hermeneutics of Indian culture as

that field in which the deeper meaning of the symbol is displayed and communally encoded through ritualization (Timalsina 2006).

I give primacy to ethnographic sources of authority over textual sources. The value of textual sources cannot be overstated. However, the Tantric process

of textual veiling is indisputably linked to a culture that placed emphasis on initiation, oral transmission, and the necessity of direct experience as the

essential pramana or means of knowing. If David White is correct in asserting that that which we identify as Tantra had become inseparable from

‘popular culture’ in South Asia by no later than the 10th century (White 2006), then it would be unwise to assume that Tantric exegetes were

committed to connecting all the hermeneutical dots through their writings alone.

Even a careful perusal of the primary and secondary sources on Indian aesthetics reveals but a dearth of direct connections between the generation of rasa and the religious experience of the artist engaged in the process of its generation. What few textual connections there are have been largely

teased out through the seminal works by Larson (1976), Masson and Patwardhan (1969), and Timalsina (2006). Each of these authors has addressed those

passages in Abhinavagupta’s where he appears to establish links between rasa theory and yogic absorption. As these scholars note, Abhinavagupta is

all but silent with regards to the description of the state of consciousness of the artistic performer. Is it that Abhinavagupta lacked knowledge and

experience in this regard? Or is it that his silence reflects the importance placed on the acquisition of this kind of practical knowledge through

initiation (diksa), practice (yoga-sadhana) and direct experience (anubhava)? Is his silence yet another form of exegetical

secrecy?

In asking these questions, perhaps we are advised to remember Abhinavagupta’s own understanding of the dyadic power of language to be both revelatory (anugraha) and binding (tirodhana). Larson writes: “With the rasa-dhvani theory Abhinavagupta was able to point to a function of

language which opens, enriches, and expands our awareness, not in the direction of abstraction but rather in the direction of a resonate fullness wherein

ordinary differentiations of time, space, ego, and so on are sublimated” (Larson 1976, 336). The expansion of language is a movement away from conventional

concretized forms of speech in which meaning is contracted to poetic, expressive forms of speech in which meaning is expansive. In the higher forms of

speech, language expresses itself through the suggestive forms of the arts which become the vehicle for the conveyance of rasa.

Abhinavagupta

While Abhinavagupta himself appears to have maintained within the confines of his writings an apparent distinction between religious experience and

aesthetic experience, contemporary exponents of the arts tend to articulate a very rich understanding of the relationship of their subjective experience in relationship to the

generation of rasa. It is through my conversation with these exponents—many of whom have been my teachers in the field of tabla, raga, and dance - that I have come to formulate the following reflections on the nature of religious experience within the context of Indian

classical arts. In this regard guruvacana and my own pratyaksa and anubhava are important compliments to my own readings of

primary sources, as well as the excellent translation and exegetical work of my peers and gurus working within the field of Indology and Religious

Studies more broadly.

It is my argument that the rich multileveled meanings of rasa provide a hermeneutical framework within which we can observe and make deeper

meaning of the artists’ own subjective experience as cultural expression of yogic insight.

Addressing the polyvalent meanings of rasa in its textual sources, White writes:

[I]n [the] tantric works on yogic and psychological integrations as the technical means (sadhana) to the realization of total autonomy, we

encounter the important notion of samrasa. Literally ‘of even rasa’ or ‘of the same rasa’, the term implies . . . a condition of

stasis in which the emanatory and resorptive impulses of the Absolute are balanced within the human microcosm. In the hathayogic system of the Nath

Siddhas, the rasas in question are portrayed as male and female ‘drops’ (bindu), which are lunar and solar, seminal and sanguineous, Siva

and Sakti, respectively. Realizing a state of equilibrium between the two members of this pair is tantamount to the formation of a ‘great drop’ (mahabindu), a yogic zygote of sorts, from which the new, liberated, all- powerful and immortal self of the jivanmukta emerges.

Coeval with these original Upanisadic syntheses was the scientific discipline of traditional Indian medicine, Ayurveda. It was in this field that an

important new application of the term rasa was promulgated at a very early date... as bodily fluid. This [new application] was an echo both of

Vedic identifications of rasa with the waters and of emerging metaphysical systems that identified each of the five elements with a sensory organ

and field of sensory activity. . . .

Emerging out of this Ayurvedic matrix, India’s classical theory of aesthetics, i. e., of taste (rasa) - through which the cultivated spectator

reinterpreted the raw emotions (bhavas) portrayed in drama, dance, and literature into their corresponding cultivated rasas - was

developed some centuries later.

(White 1996,186).

As White suggests, this ‘later development’ of rasa as an aesthetic tasting is one that arises upon and draws out of a rich cultural matrix of

meanings that link together medicinal understanding of bodily fluids together with Nath Siddha and alchemical understandings of the controlling and

harnessing of the flow of Siva and Sakti fluids within the body as key to the production of liberated states of being which in turn arose out of older

Vedic understanding that linked rasa to the juice of immortality (White 1996, 10-11).

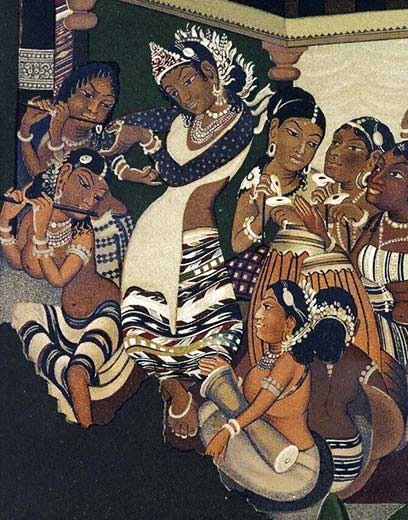

Dancing Girls of Ajanta

The suggestion of meaning elicited from the very act of Abhinavagupta producing commentaries on rasa is evocative. Clearly he was well aware of

the multiple meanings the term rasa carried. Certainly, he was aware of the philosophies of language that linked rasa to dhvani

within the fourfold schematization of language (vac) as an integrated hierarchy of Sakti. No doubt, his knowledge of the spanda and pratyabhijna traditions would have informed his understanding of this Sakti as vibration luminous self-awareness. And it is not hard to imagine

that his own practice of Tantric sadhana would have informed his perception of the intimate, continuous links between the subtle sounds heard in

yogic meditation and those sounds generated through musical performance. According to Pandey, Abhinavagupta was himself known to play the vina. No

doubt he would have drawn inspiration from texts like the Vijnana Bhairava which incorporate the Tantric meditation (dharani) of meditating on the

sound of stringed instruments. And no doubt Abhinvagupta would have appreciated and been audience to the vibrant Tantric temple culture in which stringed

instruments and the pakhawaj drum interwove mandalas of sound and rhythms that inspired the ritual dance of the devadasis. It

was perhaps in such rasa-charged environments that Abhinavagupta and other Tantric exegetes would reflect on and expound their metaphysical vision of Siva

as the dancer, spectators, and stage (Siva Sutras 3.9-12).

While Abhinavagupta is an important and intriguing source for our understanding of the culturally embedded meaning of rasa, he is by no means a

soul authority. The connections Abhinavagupta implied in his own writings were not only developed further by later exegetes, but, more importantly,

continued to express themselves in India’s cultural traditions and to be carried on in oral traditions that survive today. What was only suggested by

Abhinavagupta is articulated clearly by contemporary exponents of the arts. When textual sources are combined with a Tantric hermeneutics of culture

grounded in the living oral traditions a rich integrative interpretation of rasa emerges.

In this essay I identify the ‘aesthetic tasting’ dimension of rasa as an expression of the external, emanatory aspect of sakti that is

the consequence of the internalized mystical state of the artist who cultivates rasa through an inward move precipitated by the basic principles of yoga:

posture, regularization of breath, withdrawal, and concentration. This dual faced integration of an internalized and externalized state of consciousness

(Forman 1999) reiterates a dyadic template that connects cosmogenic descriptions of the opening and closing of the eyes of Siva with the creative and

absorptive emanations of the mandala with the expansive and regressive dimensions of visarga sakti with the outward and inward forms of

temple and private Tantric ritual with the extrovertive and introvertive forms of mystical absorption (samadhi). In all the ways that the dynamic

consciousness of the universe is at once internally grounded and yet outwardly expressive, so the artist brings forth rasa as the externalized projection

of her yogic absorption in consciousness.

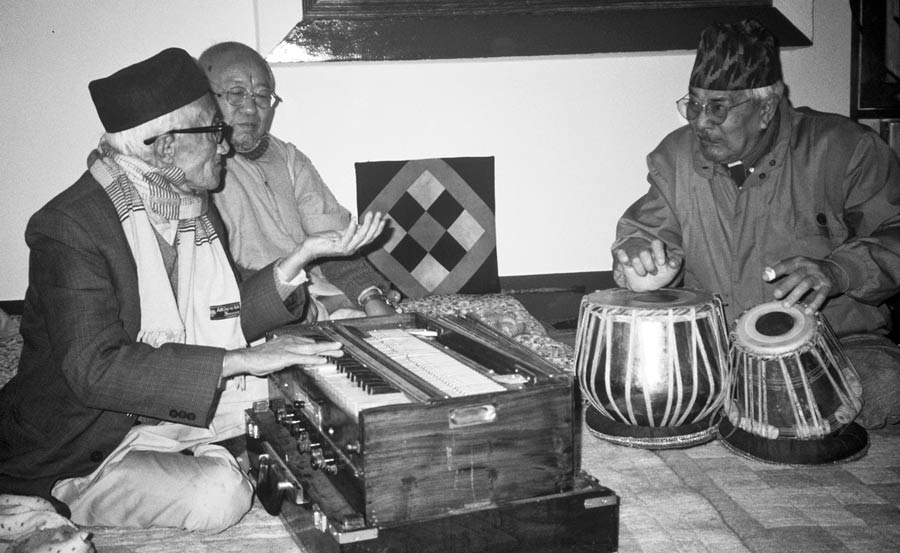

The late Pandit Shambhu Prasad Mishra accompanied by the late Pandi Samba Dev Mishra on harmonium. The late Swami Prapannacharya in attendance.

Parampara

The knowledge of Indian music and dance is transmitted entirely through the body. In the tabla traditions, there are two ways of evaluating the degree of

mastery of a student: sound quality and the ‘look of the hand’. There are six primary schools or gharanas of tabla: Varanasi, Pharukabad, Lucknow,

Delhi, Ajrada, and Pujab. Each tradition is distinguished by it compositions as well as the positioning of the hands. Like a mudra, the hand

position of the tabliya identifies the degree to which he is a true representative of his parampara. The common statement he has ‘good hands’ is

not simply a reference to sound clarity, speed, and mastery of rhythm but to actual appearance of the hands. Hands that bear the seal of the tradition are

inevitably capable of producing the right sound. In twenty years of studying tabla, I have never once witnessed an exception to this rule widely held by

tabla gurus.

My primary tabla teacher is Pandit Homnath Upadhyaya, former royal court musician and retired professor of Indian Music at Bhotahity Fine Arts Campus,

Kathmandu, Nepal. Pandit Upadhyaya is an exponent of the Benares gharana within the parampara of Anoke Lal. It was under the tutelage of

Pandit Upadhyaya that I first began to reflect on generation as rasa from the subjective experience of the artist. At that time I was nineteen years old

and was three years into what would turn into a seven year intensive study of yoga practice and philosophy under the direction of Gurumayi Chidvilasananda,

herself a student of the respected and controversial Tantric guru, Swami Muktananda. While classical Indian texts on aesthetic experience are silent with

regards to the experience of the artist, it had always been intuitively self-evident to me that the practice of music and dance, as yoga-sadhanas,

would lead to states of consciousness akin to those acquired through other yogic disciplines. For this reason it did not surprise me when Pandit Upadhyaya

expressed to me that the goal of tabla riyaz is to reach a state of awareness in which there is complete identity between the tabla player, his

rhythms, and the audience. He himself claimed that when he had reached this state, the audience would often literally vanish and he would find himself in

such a state of absorption that he experienced himself as non-distinguishable from the music itself.

In this state, he explained, is when his sadhana gives way to grace and the inner god plays through the body.

This is also the state in which the greatest aesthetic joy is transmitted to the audience.

In Pandit Upadhyaya’s description of his own experience in the context of playing tabla, we see a direct connection between the generation of rasa by the

artist and the subjective experience of the artist in the act of that generation. This connection is one that is central to understanding the link between

aesthetic experience (rasasvada) and religious experience (brahmasvada). While the textual sources on this connection are largely silent

(with a few notable sections) contemporary artisans are not. Pandit Homnath’s own reflections have been reconfirmed repeatedly over the years. In the field

of North Indian classical music I reference here conversations with three of my teachers: Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Ustad Imrat Khan, and Ross Kent.

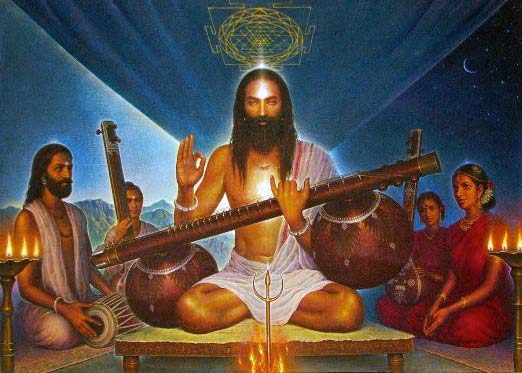

The late great Ustad Ali Akbar Khan

In the summer of 2005 I had the opportunity to attend tabla and vocal classes at the Ali Akbar College of Music in San Rafael.The Ali Akbar College was founded in 1967 by legendary sarode maestro Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. Ustad Khan was the son of the revolutionary artist Allaudhin Khan, teacher of Ravi Shankar, Nikhil Banerjee, and his daughter, the great Sarada Ma, who, like the devadasi dancers, performed only for God. At the college Ustad Khan taught the Maihar gharana of raga performance (vocal and instrumental) according to the traditional practice methods of his parampara until his death in 2009.

That summer I spent an afternoon talking with Ustad Khan in his practice and shrine room at his home near the college. I asked him to comment on his own

experience as an artist and how that experience relates to the generation of rasa. After discussing the eight primary rasas he turned his

analysis towards the bhavas or moods connected with those rasas emphasizing that the artist himself must be ‘possessed’ by the raga in order to convey the correct rasa(s) of the raga. Without such possession, he claimed, even if the raga is

rendered with technical precision the fullness of the rasa will not be generated and felt by the audience. In this context he pointed out that one

of the distinctions that one finds between younger artists and older, more seasoned artists is that the younger artists, while perhaps endowed with great

speed and an impressive array of difficult compositions will lack the correct feeling in regard to their performance. This absence of feeling, he declared,

reflects an absence of an ability to be possessed by the raga which is itself ultimately a goddess or manifestation of sakti as sound. “Unless the

Raga Devi enters you,” he said, “you will not convey the raga in its fullness.”

Ustad Khan’s discussion of possession in relation to the rendition of ragas evokes provocative connections to the Kaula Tantric emphasis on samavesa. In the context of Tantric liturgy and yoga practice, the upasaka seeks pervasion by the deities of his worship. This pervasion

is a transmission of clan nectar that is realized externally through the ritual consumption of fluids and internally through the transmutation of

consciousness through yogic control of the vital organs and breaths in the process of raising the kundalini-sakti. In the state of samavesa, the upasaka mystically consumes that rasa which is itself that immortalizing liquid that accomplishes the goal of

Tantra: to make one like the gods. In the Kaula Tantric texts ‘becoming like the gods’ is identified as recognition of the spanda-sakti as the

vibratory core of all reality. As vibration, the spanda is a sonic manifestation of divinity whose interwoven aspects are melody (raga)

and rhythm (tala).

At the culmination of our discussion, Ustad Khan took me over to his personal shrine, which consisted of seven levels of photos of teachers, saints, and

deities alongside murtis and the requisites of Tantric puja. It did not surprise me that at the center of this shrine was a beautiful

crystal image of the Sri Yantra. This ubiquitous symbol of Mahadevi had been tracking me for many years at that point, beginning with my field research in

Nepal in 1996-7 where my studies of the Nityasodasikarnava and commentarial texts had led into an ethnographic study of contemporary Sri Vidya

traditions, a study that illumined direct links between Sri Vidya theology and practice and contemporary exponents of the classical arts. The late Sambha

Prasad Mishra, one of the grand teachers of Homnath Upadhyaya, was the first to explain to me the means by which the Sri Yantra articulates a divinely

inspired mathematic vision of the intersection of infinite rhythmic possibilities within the framework of the master tala, Tin Tala, whose

condition as the King of Rhythms is grounded in the fact that number 16 is identified as the condition of perfection (purnatvam).

Sri Yantra

What Ustad Khan then shared with me revealed that a similar understanding of the Sri Yantra with regards to the possibilities of melodic expression and

composition is also adhered to within the Maihar gharana. He explained that the Sri Yantra as a symbol of the body of the goddess represents and

makes possible the revelation of all the forms and combinations of ragas which are, ultimately, he explained, all emanations of the one goddess. “All ragas - as devis - emanate from and return to the one great Devi, just as all rasas emanate from the central rasa of santa.

A master of raga is one who can evoke all of the manifestations of raga within himself and out through his rendering of the raga

which itself is like a projection or emission of sakti. However, this is just the theory. Its application is what matters and that is something

about which I am not going to tell you. If you want to experience this then you have to keep practicing tabla and deepen your knowledge of raga

and dance.”

It did not surprise me that Ustad Khan was silent regarding his own worship of the Sri Yantra. That he claimed to worship and meditate on the image every

day did not surprise me either. A deep veneration for this complex polyvalent Tantric image within the contexts of India’s artistic traditions was one I

had witnessed repeatedly in my studies and travels. It also did not surprise that as I heeded Ustad Khan’s advice and chose to turn my interests towards

classical dance I would continue to find the principles and form of the Devi-mandala would continue to provide hermeneutical insights.

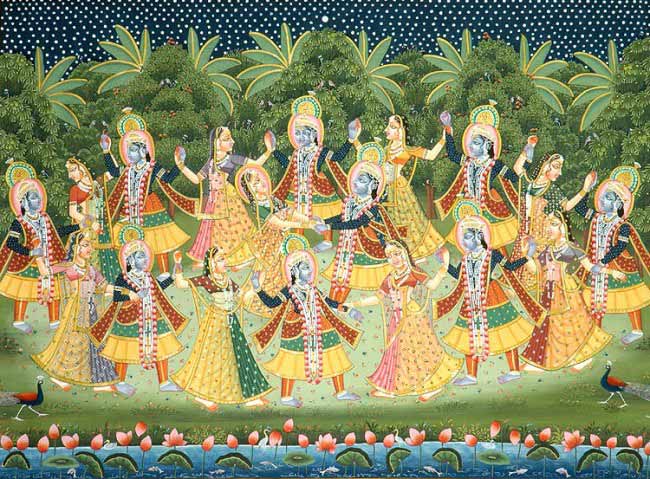

The Rasa-lila dance of Radha and Krishna

Pandit Nataraj Ramakrishna and the Devadasi Andhra Natya Tradition

The connections between Indian temple dance and Tantra are direct and multiple. The lord of Saiva Tantra is Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance. His dance

embodies the Five Powers: creation, sustenance, destruction, concealment, and revelation. His dance is the totality of the cosmos. Its ultimate purpose is

recognition, pratyabhijna. By dancing, God creates, sustains, destroys, conceals, and re-cognizes himself by means of grace. What is the means of

this re-cognition?

The connections between Indian temple dance and Tantra are direct and multiple. The lord of Saiva Tantra is Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance. His dance

embodies the Five Powers: creation, sustenance, destruction, concealment, and revelation. His dance is the totality of the cosmos. Its ultimate purpose is

recognition, pratyabhijna. By dancing, God creates, sustains, destroys, conceals, and re-cognizes himself by means of grace. What is the means of

this re-cognition?

It is the reflective illumination that occurs through

the coalescence of luminosity with self-reflective awareness.

For luminosity to know itself it must be embodied.

Through embodiment the Self can be in touch with itself

and thereby come to a condition of recognition.

For this reason, Siva dances the lila of creation.

In this regard the Siva Sutra proclaims the Self to be a dancer. This is more than theological metaphor. Culturally and historically it is an

interdisciplinary reference to the long-standing tradition of classical dance in India, a tradition identified as a ‘5th Veda’ and a tradition

that had developed by the 9th century into a primary form of temple worship through the devadasi cultures found in many regions of

India by this time. That this temple culture would arise at the time of the ascendancy of Tantra as the dominant religious ideology and practice of much of

South Asia is no accident. Reading culture and society together with the diversity of texts of this time as a holistic and integrated ‘textual system’ in

which written texts take embodied form as socio-cultural expression we then see the devadasi tradition as an integral expression of the Tantric

vision of an integrated mandala system in which living kings connect to a divine king through a clan nectar that flows into the body politic

through an elaborately orchestrated hierarchy of state rituals orchestrated within the state sponsored temple system and replicated, fundamentally, as

individual puja.

In this context, the multileveled meanings of rasa must be excavated for a deeper understanding of how the aesthetic sentiment of dance linked the devadasi tradition to the heart of the Tantric culture of which it itself was its pinnacle representation as the mastery of dance for the eyes of

God only. In this context, the devadasi’s body was to be the vehicle of rasa for the aesthetic satisfaction of the image within the

temple. When I asked Pandit Nataraj Ramakrishna about the purpose of the devadasi dance he answered, “While dancing have you ever witnessed your

own deeper personality emerge out of you and stand before you as your own Beloved? This was the purpose of the devadasis. Through dance they

infused the temple image with their own awakened personality.” When pressed to clarify his use of the term ‘personality’ the well-educated and articulate

master of Andhra Natya dance explained that by personality he meant the equivalent of the jiva or life essence of the dancer, which becomes

spiritually charged by the dance. Significantly, he attained the enlivened jiva as itself a refined rasa that was to be tasted by the

deity of the central image and then, in return, tasted by the temple dancer who receives her offering of rasa as the very same ‘blessing power’ that

sanctifies the blessed food offering she receives at the culmination of the dance.

The late Pandit Nataraj Ramakrishna,

exponent of the Andhra Pradesh Devadasi dance tradition.

The connections between the temple liturgies detailed in the Silpa Sastras, the rituals of the Kaula Tantrikas, and the aesthetics are

intriguingly binding. As a form of worship, or puja, the devadasis dance form is intended to please the lord of the inner sanctum. In

this role, she is a priestess whose own body conveys those aesthetically encoded messages of enjoyment by which body gestures, abhinaya, conveys rasa. As a Tantric messenger she brings to her lord and husband a knowledge contained in that continuum of rasa that binds refined

aesthetic moods to bodily fluids identified as microcosmic equivalents of the geological and cosmological life energies that all reflect the flow and

vibration of sakti within the extended interwoven body of the Tantric godhead.

Conclusion

These reflections constitute but preliminary reflections on the relation of internalized yogic absorption to the generation of rasa in the arena of the

cultural arts. I have argued that this relationship mirrors the dyadic structure of divine consciousness which patterns itself at all levels of creation as

at once inwardly focused and outwardly expressed. At the ultimate level, Siva gazes within at his own wondrous Self while manifesting externally, within

that infinite Self, his own being as the cosmos. In ritual liturgy, this pattern is mirrored and reflected upon through the emanation and dissolution of

the mandala, or the emanation of yogic prana into the deity and then its reabsorption. Within the context of yogic sadhana, the

adept explores the aspects of sadhana as both internalized absorption (nimilanasamadhi) and externalized unitive awareness (unmilanasamadhi). Grounded within his own being, the adept attains grounding in the rasa of his own Self. Opening his eyes, he emanates

the wonders and powers of his realization onto the world that appears before him. In the same way, the artist, as a yogin, cultivates through her art the

capacity to still and focus the mind, making possible stabilization within the essential Self and the ability to harness the essential feeling necessary

for the proper generation of rasa which emerges through her art as an externalized projection of the artist’s internalized state.

This dynamic is evident in the painter’s projection of a mandala from his visualization, in the tabla player's grounding in prana and

absorption, in the singer's and instrumentalist's inward immersion in the raga, and in the dances of the Devadasis whose sacred dances for God gave

externalized projection to the immersion in the rasa of devotion, emanating outward and into the God the rasa of love as the supreme offer to

their Beloved.