Naropa: The Dauntless. Tibet. Google Cultural Institute.

Editor’s Note:

Daniel Odier is a Swiss author and screenwriter and a prolific writer on Eastern religious traditions, especially Tantra, who has experienced a mystical

initiation from a tantric dakini, Lalita Devi, in Kashmir. Odier also received dharma transmission from Jing Hui, abbot of Bailin Monastery and dharma

successor of Hsu Yun, using the name "Ming Qing". He founded the Tantra/Chan centre in Paris, which operated from 1995 to 2000, and has taught

courses on Eastern spiritual traditions at the University of California.

Lea Horvatic:

Can you tell us how you first found yourself on the path of Tantra and Ch’an Zen tradition? What were the big turns that lead you here?

Daniel Odier:

I first came in contact with the Chan tradition through D.T. Suziki’s essays on Zen Buddhism when I was 16. l was fascinated by the freedom and the

audacity of the Chinese masters from the Tang dynasty period. But, at that time, there was no practice in Geneva where I lived. Later, at 22, I went to

India and met Kalou Rinpoché and the Tibetan Tantric tradition. I studied with him for the next seven years. But after the initial fascination, I found

the tradition too complex, too culturally marked and far. Kalou Rinpoché was a marvelous master, very open to other traditions in the Buddhism realm, and

of course deeply connected to the source of kashmirian shaivism. He advised me to go to Kashmir to find this tradition, which was still taught as it was

1,000 years ago—a very direct and non-progressive path. After some misadventures, I finally found my master, Lalita Devi, and went to a deep non-stop and

intense immersion in the tradition.

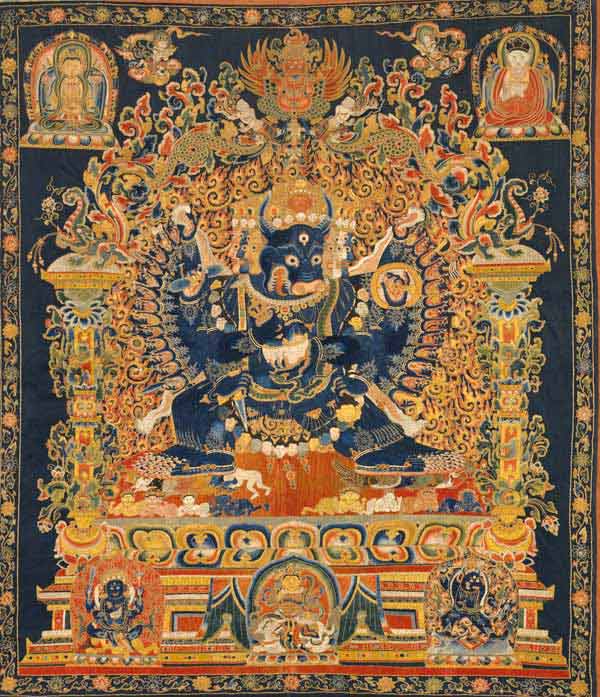

Mahakala, Protector of the Tent, ca. 1500. Central Tibet.

Distemper on cloth; Image: 64 x 53 in. (162.6 x 134.6 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Gift of Zimmerman Family Collection, 2012

Lea Horvatic:

Can you tell us more about your teachers and transmissions that you’ve received?

Daniel Odier:

From Kalou Rinpoché, I just received the basic practice. From Lalita, I received Mahamudra and the most important things in the Kashmiri practice: Tandava,

the mystical dance—which is the only physical yoga in the tradition—the yoga of emotions, the vizualisation of Matsyendranath, and the yoga of touch, which

are the four practices of the Spanda school, my lineage. I received too the Kali practices, wild and savage, which I describe in my forthcoming book on

Kali that will be published by Inner Traditions this year. Fom my Ch’an master, Jing Hui, I received the transmission of Sifu or master, the

flywhisk, the robe, the mala.

Lea Horvatic:

Would you please elaborate more on the subject of Sahajiya, the path of spontaneous awakening which you practice and teach?

Daniel Odier:

Sahajiya is the expression of spontaneity that fosters mental silence. It’s an effect of the four practices mentioned above. It’s total freedom of

expression and action, freedom of emotions rather than control, creativity, non-repetitiveness in everything. It’s a constant move of the body, mind and

emotions. Awakening is the source, rather than a destination that practice reveal.

Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali (detail), 18th–19th century. Mongolia.

Tung oil stucco, wood, gold, cinnabar, and other pigments; 7 1/2 x 6 in. (19.1 x 15.2 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Kate Read Blacque,

in memory of her husband, Valentine Alexander Blacque, by exchange, 1948

Lea Horvatic:

You wrote numerous books on Tantra, translated in eight languages, and taught extensively on Tantra and Buddhism at several American universities. What

would you say about the approaches that may differ in Ch’an Zen, Tibetan Masters and the teachings of Abhinavagupta?

Daniel Odier:

There are many differences in the formal approach, but much less if you penetrate the core, especially between Ch’an and Spanda schools. And I was very

surprised in China to discover that our main text, the Vijnananabhairava Tantra, was known and used and translated in Chinese very early after it was

written down. The accent in both traditions is to abandon dogma, beliefs and certainties—that everything is real and that one should not cut anything human

in order to attain mystical experience. Both schools insist on spontaneity as a sign of achievement. The heart transmission, direct and without words, is

essential. Both schools recognize the importance of the body in the process. Abhinavagupta could be a Ch’an master, Zhao Zhou a Kashmirian master. In

China, many Ch’an master are tantrics too. There is a difference in the practice. In Ch’an you walk, sit and shut your mouth. In Spanda, you dance, sit and

shut your mind.

Lea Horvatic:

What is their integrating motif and how do you incorporate it in your teachings?

Daniel Odier:

Naturalness, freshness, non-repetition, great freedom in the mind, the emotions and the body. I integrate them in living it.

Vajrabhairava, early 15th century. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China.

Embroidery in silk, metallic thread, and horsehair on silk satin; 57 1/2 x 30 in. (146.1 x 76.2 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993

Lea Horvatic:

What is the nature of Kaula tradition? How are the paths of Siddhas and Naths merged there?

Daniel Odier:

The essence of the Kaula path was transmitted in Kashmir by Matsyendranath. The Mahasiddha from Assam and Abhinavagupta mention him in the opening of his

magistral, “Tantraloka.” The essence of this teaching is the union of Shiva and Shakti on the mystical and physical level. The essence of the teachings

appears in the “Kaulajnananirnaya Tantra” from Matsyendranath. It’s the ancient layer of the tantric tradition. The so-called “left hand” or “path of the

women” practices are coming from this deep layer. They demand a deep mystical experience prior to any sexual practice. This means it’s largely unattainable

for Westerners. The heart is the center of consciousness and the manifestation of the deepest level of mystical experience—the light of Siva. This infinite

reality has the power of lightning. The Kaula practice rituals to transform the ordinary body into the 50 sacred places of India and to create the absolute

vibration of the mystical heart. It’s revealing the cosmic body.

Lea Horvatic:

You are a prolific writer, not only on the topics already mentioned, but also a novelist and a screenwriter. You have been lauded by Annais Nin as “an

outstanding writer and a dazzling poet.” Tell us what this process of writing holds for you.

Daniel Odier:

The writing process is for me totally out of the mind. It’s a natural flow out of my control—more like a painter than a writer. It’s a kind of automatic

writing that surprises me. It’s an expression of freedom.

Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali (detail), 18th century. Tibet.

Distemper on cloth; Overall with mounting: 56 x 25 1/2 in. (142.2 x 64.8 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. W. de Forest, 1931

Lea Horvatic:

In 1995 you formed a Tantric school in Paris, and disbanded it in 2000 in order to encourage more independent practice. What trend did you find developed

among practitioners who came to study there that was counterproductive to their progress?

Daniel Odier:

I find that most of the so called “spiritual practices” are counterproductive as well as the idea of group. It doesn’t help expression of freedom, and

tends to develop a kind of conformism which is the absolute opposite of the Tantric traditions. This feeling is more and more important for me. Tantric

tradition is totally anarchic in the deep sense, so I try to make this anarchic dimension alive in everything. Most of the sanghas are protection against

the unknown, and I want to plunge in the unknown with no rules, no limits, no false morals—just consciousness!

Lea Horvatic:

Your new book, The Doors of Joy: 19 Meditations for Authentic Living, is a great manual aimed at those who have not yet found the sacred

in the little moments of life. Can you please tell us more about it and how it had come into existence?

Daniel Odier:

It came to existence because my publisher asked me to write a book without spiritual or traditional references—a book that any human could read and benefit

from. Simple and deep. And I think the challenge was great. It’s very difficult to go just to the fundamentals of human experience, to analyse why we don’t

know Joy. What is blocking us? It was a long process, like a detective work (to write the book). Just the fundamentals, nothing more. I think it’s an

anarchic manual. I smile!

Buddha Amoghasiddhi with Eight Bodhisattvas (detail of central figure), ca. 1200–1250. Central Tibet.

Distemper on cloth; 27 1/8 x 21 1/4 in. (68.9 x 54 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Purchase, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Philanthropic Fund Gift, 1991

Lea Horvatic:

Can you offer us some titles and authors whose books made a great impact on your own life and being, and which may be a valuable read for others too?

Daniel Odier:

For the Ch’an: The Poetry of Enlightenment: Poems by ancient Ch’an masters by Ch’an master Sheng-yen (Dharma Drum Publication, 1987). This small

book is always with me. Everything is there through poetry. It’s a marvel—a real pocket and soul book! Also, The Compass of Zen by Zen Master

Seung Sahn (Shambala editions, 1997). Another magical book, clear like a sword. And Zen Essence: The Science of Freedom by Thomas Cleary

(Shambala, 2000). The teachings of the classical Chinese masters. A marvelous classic, the essence of the tradition.

For the tantric tradition: The Stanza on Vibration by Mark S. Dyczkowski (Suny, 1992). The great book of the Spanda tradition, very deep and rich.

Also, Ecstatic Spontaneity: Saraha’s three cycles of Doha by Herbert Guenther (Asian Humanities Press, 1993). Poetry is ideal to get the substance

of tantra. Finally, Passionate Enlightening: Women in tantric Buddhism by Miranda Shaw (Princeton University Press, 1994). To understand the

importance of the feminine in the tantric tradition.