On 18-June-2004, a 6.5-foot statue of dancing Siva was unveiled at CERN by its Director General, Dr.

Robert Aymar. A special plaque next to the statue explained the traditional symbolism of Siva’s dance

also quoted Fritjof Capra a particle physicist himself, ‘For the modern physicists, then, Shiva’s dance

is the dance of subatomic matter.’ The statue, a gift from the Indian Government, was to commemorate

the long association of Indian scientists with CERN that dated back to 1960s.

Fritjof Capra became a well-known name among ‘New Age’ aficionados as well as serious thinkers

(not necessarily mutually exclusive groups) in the 1970s. His fame in India has been largely through

the way he integrated the image of dancing Siva with the dynamic nature of sub-atomic particles. Capra wrote quoting Ananda Coomaraswamy (edited by Zimmer) in his cult classic 'Tao of Physics':

For the modern physicists, then, Shiva’s dance is the dance

of subatomic matter. As in Hindu mythology, it is a continual

dance of creation and destruction involving the whole cosmos;

the basis of all existence and of all natural phenomena.

Hundreds of years ago, Indian artists created visual images

of dancing Shivas in a beautiful series of bronzes. In our

time, physicists have used the most advanced technology to

portray the patterns of the cosmic dance. The bubblechamber

photographs of interacting particles, which bear

testimony to the continual rhythm of creation and destruction

in the universe, are visual images of the dance of Shiva

equalling those of the Indian artists in beauty and profound

significance. The metaphor of the cosmic dance thus unifies

ancient mythology, religious art, and modern physics. It is indeed,

as Coomaraswamy has said, ‘poetry, but none the

less science’ (The Tao of Physics, p. 272).

It was the powerful way in which the physicist–author wrote about the

parallels between the dancing Deity and the web of relations emanating

and dissolving in the realm of sub-atomic particles that ultimately

led to the establishment of a Siva statue at CERN.

THE DANCING SIVA

For Hindus who had

been constantly abused

as worshippers of

barbarous grotesque

deities, the book and its

imagery came as a sort

of scientific vindication

of ancient wisdom.

How the ‘Tao of Physics’ actually affected the psyche of educated Hindus

is in itself an interesting phenomenon. Just a few years before its

publication, Dravidian racists had put up a poster which showed the

very cosmic dance as nonsensical superstition with American astronomers

putting their feet right on the crescent moon adorning the dancing

Siva – thus Siva was under the feet of the American astronaut. For Hindus

who had been constantly abused as worshippers of barbarous grotesque

deities, the book and its imagery came as a sort of scientific vindication

of ancient wisdom. Interestingly, while Capra saw the symbolism

of Siva’s cosmic dance in the sub-atomic particle trajectories captured

in the bubble chamber, the famous chemist, Illya Prigogine who

was best known for his concept of dissipative structures, had used the

dance of Siva to symbolize the thermodynamic ‘theory of structure, stability and fluctuations.’ Siva’s cosmic dance, even as a metaphor,

thus pervaded both the sub-atomic and molecular levels

of reality. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Carl Sagan saw

in the cyclic cosmic dance of Siva ‘a kind of premonition of

modern astronomical ideas’ like the oscillating universe. More

recently Dr. V. S. Ramachandran, the modern cartographer of

the dynamic brain, used the metaphor of the dance of Siva in

an existential sense: “If you are really part of the great cosmic

dance of Shiva, other than a mere spectator, then your inevitable

death should be seen as a joyous reunion with nature rather

than a tragedy.” One wonders if there is another spiritual/

artistic/mythological symbol like that of the dancing Siva that

humanity has created which can accompany our own understanding

of the universe, inner and outer!

Unfortunately, the interest mostly stopped right there. In 1982, Fritjof Capra delivered a series of lectures

at Bombay University, arranged by University Grants Commission of India that accompanied

the publication of his next book, ‘The Turning Point.’ In the lecture series, the physicist enlarged upon

his vision and spoke of a systems view of life. Interestingly among the Hindu circles, the founder of

the trade union with Indic ideology BMS (Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh: Association of Indic workers),

Dattopant Thengadi alone seemed to have been aware of the importance and relevance of Capra’s

expansive vision in relation to their ideology – particularly in the larger context of ‘Integral humanism,’

an ideology advocated by Jan Sangh (a party perceived as rightwing, though such categories do not

accurately apply to Indian politics) ideologue Deendayal Upadhyaya.

PARADIGM SHIFT

In ‘The Turning Point’ (1982), Capra explored how the changed vision

of nature emanating from the ‘new physics’ also changes the

way we look at life, our psychology, society, politics, economics,

and environment. He identified the interconnectedness that the

theoretical physicists like David Bohm were talking about in such a

powerfully poetic language as having an impact on the way other

disciplines viewed and approached their own subject matter. In

general, a ‘paradigm shift’ has been happening, he claimed, from

the Newtonian-Cartesian essentially mechanistic vision of the universe

to a more holistic, interconnected, organic vision of universe.

From a reductionist mechanical view of life, we are moving towards a

systems view of life. From Freudian and behaviorist models in psychology,

we are moving towards the more holistic and humanistic approaches

to the psyche propounded by Maslow and Jung. In economics,

Capra also identified a shift as reflected in the ‘Buddhist economics’

of E. F. Schumacher. His book explored all these developments in

detail.

Here Capra takes a

sympathetic view of

Marx that would later

become central to

ecological movements

throughout the world.

Here Capra takes a sympathetic view of Marx that would later become

central to ecological movements throughout the world. After the collapse

of the Soviet Union, many Marxist activists as well as scholars

have shifted their focus to an ecological critique of capitalism. Capra

does see Marx as a sort of pioneering holistic thinker far ahead of his

times:

Many of these experiments were very successful for a while,

but all of them ultimately failed, unable to survive in a hostile

economic environment. Karl Marx, who owed much to the

imagination of the Utopians, believed that their communities

could not last, since they had not emerged "organically" from

the existing stage of material economic development. From

the perspective of the 1980s, it seems that Marx may well

have been right (The Turning Point, p. 203).

After the collapse of

the Soviet Union, many

Marxist activists as well

as scholars have shifted

their focus to an

ecological critique of

capitalism

In Capra’s assessment, Marx comes out as a pioneering, organic

process-philosopher studying social dynamics:

Marx's view of the role of nature in the process of production

was part of his organic perception of reality, as Michael Harrington

has emphasized in his persuasive reassessment of

Marxian thought. This organic, or systems view is often overlooked

by Marx's critics, who claim that his theories are exclusively

deterministic and materialistic (The Turning Point,

p. 207).

However, Capra makes it clear how he differs

from Marx:

The Marxist view of cultural dynamics,

being based 'On the Hegelian notion

of recurrent rhythmic change, is not

unlike the models of Toynbee, Sorokin,

and the I Ching in that respect. However,

it differs significantly from those

models is in its emphasis on conflict

and struggle. ... Therefore, following

the philosophy of the I Ching rather

than the Marxist view, I believe that

conflict should be minimized in times

of social transition, (The Turning Point,

p. 34-35).

In terms of the history of political ecology, others

differ from Capra’s assessment of Marx. As

economist Joan Martinez-Alier points out, the neglect

of ecology has been inherent in Marxism

from the very beginning as seen in the rejection

of the work of Sergi Podolinsky by Marx and

Engels. Podolinsky, an Ukrainian physician and

socialist, tried to integrate other issues with the

theory of value of the laws of thermodynamics –

particularly the second law. Martinez-Alier points

out that Podolinsky had analyzed the energetic

of life and had applied it to the dynamics of economic

system. Podolinsky had argued that the

human labor “had the virtue of retarding the dissipation

of energy, achieving this primarily by agriculture,

although the work of a tailor, a shoemaker

or a builder would also qualify, as productive

work, affording 'protection against the dissipation

of energy into space,'“ (Martinez-Alier, Energy,

Economy and Poverty: The Past and Present

Debate, 2009, p. 40).

TOWARDS ECO-FEMINISM

The Turning Point also reveals a growing influence of eco-feminists on

Capra like Charlene Spretnak, Adrienne Rich, and Hazel Henderson.

Spertnak seems to

advocate the

indigenous Goddess

tradition of Marija

Gimbutas, according to

which the Kurgan

people descending

from the steppes

brought with them

patriarchy and sky

gods and destroyed the

earth-goddess tradition

then prevalent

throughout Europe.

Particularly important is Charlene Spretnak, an eco-feminist. Capra coauthored

with Spretnak ‘Green Politics,’ subtitled ‘Global Promise’

(1984). The book projects Green politics as an alternative politics

emerging from the new vision of reality. In 1983, 27 parliamentarians

elected in West Germany belonged to Green Party – a new phenomenon

then. Capra and Spretnak saw this as the Greens transcending ‘the

linear span of left-to-right.’ The Marxist influence was very much visible.

What was even more visible was the way Marxists within the Greens

were out of sync with the cardinal principles of the holistic Greens. Capra

and Spretnak record:

We began to perceive friction between the radical-left

Greens and the majority of the party as we travelled around

West Germany and asked our interviewees whether a particular

goal or strategy they had described was embraced

by everyone in this heterogeneous party: ... 'Does everyone

in the Greens support nonviolence absolutely?' we asked.

'Yes... except the Marxist-oriented Greens.' 'Does everyone

in the Greens see the need for the new kind of science and

technology you have outlined?' 'Yes ... except the Marxistoriented

Greens. 'Does everyone in the Greens agree that

your economic focus should be small-scale, worker-owned

business?' 'Yes ... except the Marxist-oriented Greens.' (pp.

20-1)

Spertnak seems to advocate the indigenous Goddess tradition of

Marija Gimbutas, according to which the Kurgan people descending

from the steppes brought with them patriarchy and sky gods and destroyed

the earth-goddess tradition then prevalent throughout Europe.

Spertnak herself had written a book on the lost goddesses of early

Greece. This of course is the ‘Aryan invasion Theory’ of Europe that

was later relegated to the sidelines of the academic stream in the West.

Marxist historian and polymath D. D. Kosambi had attempted a similar

model for ancient Indian history.

DISCOVERING THE DYNAMIC UNIVERSE

Heisenberg was

intrigued when Capra

showed how ‘the

principal Sanskrit terms

used in Hindu and

Buddhist philosophy -

brahman, rta, lila,

karma, samsara, etc. -

had dynamic

connotations’ (p. 49).

Capra’s next important book, (‘Uncommon Wisdom,’ 1986), was about

his encounters with the remarkable personalities who shaped his worldview.

In some way, this book is an autobiographical account of the evolution

of his worldview. It was in this book that Capra documents Heisenberg

being ‘influenced, at least at the subconscious level, by Indian philosophy’

(p. 43). During his second visit to Heisenberg, Capra shows

the venerable old man of physics the manuscript of ‘Tao of Physics’. To

Capra the ‘two basic themes running through all the theories of modern

physics, which were also the two basic themes of all mystical traditions’

are the ‘fundamental interrelatedness and interdependence of all phenomena

and the intrinsically dynamic nature of reality.’

Interestingly Heisenberg, while agreeing with Capra

on his interpretation of physics, states that though he

was ‘well aware of the emphasis on interconnectedness

in Eastern thought.

Even the great minds

like Heisenberg, while

not unaware of the

depth of Indian culture

and philosophy, were

still susceptible to the

stereotype of a passive,

fatalistic, mystic India

However, he had been unaware of the dynamic aspect of the Eastern

world view.’ Heisenberg was intrigued when Capra showed how ‘the

principal Sanskrit terms used in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy - brahman,

rta, lila, karma, samsara, etc. - had dynamic connotations’ (p. 49).

Even the great minds like Heisenberg, while not unaware of the depth

of Indian culture and philosophy, were still susceptible to the stereotype

of a passive, fatalistic, mystic India. It is interesting to note that Capra

could find dynamism in the terms, especially Karma, for the term has

been singled out in academia for stereotyping Indian culture as fatalistic.

There is also the encounter with Geoffrey Chew – the physicist who

pioneered the S-Matrix theory that today survives largely in string theory.

He also recounts how he was shocked to find parallels between his

own formulation and the philosophical vision of ancient Buddhists (particularly

Mahayana school) when his son in senior high school pointed

it out to him (p. 53). Comparing David Bohm, another cult-physicist

who also looked for a deeper order under the quantum realm, Capra emphasizes the influence of J. Krishnamurthy on both David Bohm and

Capra himself.

The book wades through the thoughts of anthropologist and cyberneticist

Gregory Bateson, whose emphasis was on the connections and circularity

of cause-effect relations, particularly in biological systems.

Capra also details his interactions with psychiatrists

R. D. Laing and Stanislav Grof. To Capra they signified

a shift from Freudian psychology, while sharing a

deep interest in Eastern spirituality and a fascination

with ‘transpersonal’ levels of consciousness.

To Capra, Chi is ‘a very

subtle way to describe

the various patterns of

flow and fluctuation in

the human

organism’ (p. 160).

In medicine, he emphasizes holistic medicine. When he talks of the

Eastern medical systems, it is Chinese medicine and Chi that get mentioned.

It is through Margaret Lock, a medical anthropologist, that the

physicist gets his knowledge of the Eastern medical system. To Capra,

Chi is ‘a very subtle way to describe the various patterns of flow and

fluctuation in the human organism’ (p. 160). What he says for Chi can

also apply to Prana as well, and this framework allows those who synthesize

Indian knowledge systems with modern science escape the

Aristotelian/Cartesian binary trap of vitalism. Another very important person

in the book is Hazel Henderson, the author of ‘Creating Alternative

Futures.’ Often described as an iconoclastic economist and futurist,

one important aspect of Henderson’s thinking is, according to Capra,

her prediction that ‘energy, so essential to all industrial processes, will

become one of the most important variables for measuring economic

activities’ (p. 236). Here again she has been anticipated by Podoloinsky.

Henderson today champions the cause of what she calls ethical

markets.

What he says for Chi

can also apply to Prana

as well, and this

framework allows those

who synthesize Indian

knowledge systems with

modern science escape

the Aristotelian/

Cartesian binary trap

of vitalism.

Belonging to the Universe’ (1991) is a dialogue between Capra, and

David Steindl-Rast, a Benedictine monk. Thomas Matus, another Catholic

theologian, was also present during this exchange. Here Capra reveals

how he turned away from Catholicism, the religion of his birth,

and ' found very striking parallels between the theories of modern science, particularly physics [which is Capra’s

field], and the basic ideas in Hinduism, Buddhism,

and Taoism.' Then he reconnects with the

religion of his birth through David Steindl-Rast.

Here one sees how Capra, a lapsed Catholic

now returning with an acquired Eastern heritage,

struggles to belong to a common human spiritual

heritage. He says: "Now Juliette (his daughter) is

two, and soon she'll be at the age of stories.

I want to tell her tales from the

Mahabharata

and the other Indian stories, the Buddhist stories,

and some of the Chinese stories. But I certainly

also want to tell her Christian and Jewish and

Western stories of our spiritual tradition and Sufi

stories, too" (p. 4).

However, there are problem areas. For an Indian

reading this conversation, he might find how

amazingly Capra’s questions reflect his own, and

some of the answers that Steindl-Rast gives are

elusive and not exactly what one can call honest

(For an example, see pages 78-9). In hindsight,

Capra might not have known then, but both Matus

and Steindl-Rast would have known for sure,

that Mother Teresa was definitely engaging in

conversion activity and that, more often than not,

the native spiritual traditions were branded by

missionaries as agents of ‘oppression, exploitation,

human misery,’ with secular terms that are

the equivalent of ‘Satan’ and ‘Devil’ of the bygone

medieval and even early colonial ages,

when inquisition was openly called Inquisition.

Nevertheless this book is important for Hindu

scholars who want to study and have dialogue with Christianity. It reveals the inner churning happening in the Christian psyche - not at the institutional

level perhaps but at the individual level. If Hindus want to have a global Dharmic network as

they often imagine, then they have to seriously look for networking nodes in such spaces. Capra also

provides an insight into how Christianity created a new narrative of its missionary activities – which remain

almost the same as it was during the colonial times, yet couched in a new language that even

the admirers of Eastern systems in the West would accept.

In EcoManagement (coauthored with Ernest Callenbach, Lenore Goldman, Rudiger Lutz and Sandra

Marburg, 1993), Capra proposed ‘a conceptual and practical framework for ecologically conscious

management.’ In 1995, he co-edited a collection of essays with Gunter Pauli, an eco-entrepreneur,

(Steering Business toward Sustainability), with essays by likeminded people in economics, business

management, and ecology, trying to chart a practical model for sustainable development through private

enterprise.

LIFE AS COGNITION: A NEW SYNTHESIS

‘The Web of Life’ (1996) is equally as important as the ‘Tao of Physics.’ It was a great integration of

evolution, ecology, and cybernetics. It was a veritable manifesto of systems biology directed towards

the common man as well as the professional biologist who lived compartmentalized lives. The book

explains in great detail how the paradigm shift much discussed in physics with the emergence of

now a century-old new physics, has also been happening in biology. The concept of biosphere formulated

by Edward Suess at the end of nineteenth century was developed by Russian geo-chemist Vernadsky.

His conception of biosphere comes closest to the Gaia theory–earth as an evolving living system

independently arrived at by James Lovelock, a bio-physicist, and Lynn Margulis, the microbiologist

who also proposed symbiogenesis which was opposed fiercely by orthodox Darwinians but eventually accepted by mainstream biology today.

The book conceptualizes evolution more as

a cooperative dance rather than a struggle for

existence. At another level the book looks at life

fundamentally as a process of cognition. This

view of life is based on the path-breaking work of

two Chilean scientists, Humberto Maturana and

Francisco Varela.

The concept of biosphere formulated by Edward

Suess at the end of nineteenth century

was developed by Russian geo-chemist Vernadsky.

His conception of biosphere comes closest

to the Gaia theory–earth as an evolving living

system independently arrived at by James Lovelock,

a bio-physicist, and Lynn Margulis

Influenced by Buddhist epistemology,

these two biologists see cognition

as not representing ‘an external

reality, but rather specify one

through the nervous system's process

of circular organization.’ Capra

quotes Maturana’s decisive statement

with agreement: “Living systems

are cognitive systems, and living

as a process is a process of cognition.

This statement is valid for all

organisms, with and without a nervous

system.” (pp. 96-97).

Another important view of biological systems developed

by Maturana & Varela team is autopoiesis.

Capra points out from the original paper of

Maturana & Varela that this model enquires not

into the 'properties of components,' but studies

the 'processes and relations between processes

realized through components.' One cannot miss

the overtone of Alfred North Whitehead’s process

view of consciousness here. In Indian culture

the autopoiesis is celebrated as Divine and we

have a name for it – Swayambu. Most of the

Lingams today enshrined in the grand splendor

of stone temples are Swayambu. So are many of

the roadside deities under the trees. In South India

a self-evolved termite mound is venerated as

a living manifestation of Divine Feminine. Autopoiesis

can be traced to the non-linear dynamics of

Illya Prigogine’s dissipative structures. And curiously,

he like Capra had used Siva’s dance as a

metaphor for the basic process of the realm he

studied – the molecular dynamics of chemical

systems. The book is a veritable odyssey into the

billion years of evolution of the phenomenon of

life at the planetary level and lays the foundation

for the future work of Capra.

DISCOVERING THE NETWORKS

The next book 'The Hidden Connections' (2002),

as the subtitle of the book suggests, aims to integrate

the ‘'the biological, cognitive and social dimensions

of life into a science of sustainability'. It

speaks of networking at the social level based

on the views of life he had presented in his ‘Web

of Life’. He sees this as already happening. One

of the hardest problems in integrating social sciences

with the physical sciences is the tendency

to ‘reduce’ social, economic or psychological

phenomena into simplistic, sweeping, and hence

often wrong as well as dangerous generalizations.

The most glaring examples are

social-Darwinism along with many

pop bio-psychological explanations

which appear in popular magazines.

In this book, Capra provides that much-needed

yet elusive connection between social sciences and other physical sciences in a non-reductionist

framework that is more importantly also workable

and can have practical applications in community

welfare and sustainable development without

compromising the freedom that a market economy

provides. From the molecular communications

networks slowly evolving in the proto-cells

of the primeval ocean to the digital social networks

connecting the planet, Capra charts out a

path for sustainable development by bringing to

notice connecting strands of life, cognition, nature

and community which have hitherto gone unnoticed.

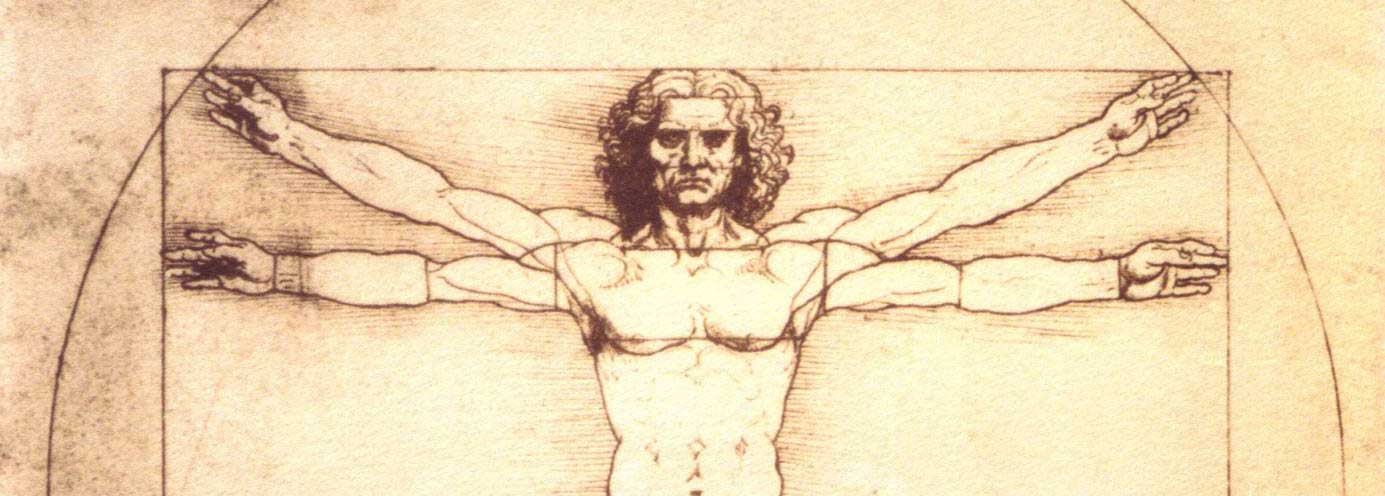

TO SCIENCE THROUGH ART:

DA VINCI AS SYSTEMS THINKER

The next two books review the science of Leonardo

da Vinci and the relevance of his science to

the present evolution of systems science. Leonardo

was known more as an artist and technological

innovator than as a scientist. For Capra, Leonardo

arrived at science through art and that

makes all the difference. Thus he avoided the pitfalls

of reductionism we encounter in Newton,

Galileo and Bacon. In ‘The Science of Leonardo’

(2007), Capra reveals many interesting dimensions

of Leonardo’s worldview that far exceeded

his own time. He was the first systems thinker according

to Capra. Leonardo envisioned rivers as

almost beings with life. In planning any city, he

would make the river an integral part of the city

landscape – almost a biological integration. He

was asked to build Cathedrals and he designed

“temples”. His architecture, his town planning,

and his view of nature – all these emerged from

his holistic understanding of nature. Capra

shares how he arrived at this vision of Leonardo

da Vinci:

As I gazed at those magnificent drawings

juxtaposing, often on the same page, architecture and human anatomy, turbulent water and

turbulent air, water vortices, the flow of human hair and the

growth patterns of grasses, I realized that Leonardo's systematic

studies of living and nonliving forms amounted to a

science of quality and wholeness that was fundamentally different

from the mechanistic science of Galileo and Newton

(Preface, XVIII).

Europe unfortunately

never adapted

Leonardo’s ideas for

city planning. However,

centuries later another

European, a Scot,

would discover a

similar organic city

planning in another

civilization.

Capra sees in the painter of The Last Supper “a systemic thinker, ecologist,

and complexity theorist; a scientist and artist with a deep reverence

for all life, and as a man with a strong desire to work for the benefit

of humanity.” Clearly in the centuries that followed Leonardo, the science

he envisioned was lost to the science of Newton, Bacon and Descartes.

One interesting aspect of Leonardo is his novel approach to

city planning. Capra points out:

It is clear from Leonardo’s notes that he saw the city as a

kind of living organism in which people, material goods,

food, water, and waste needed to move and flow with ease

for the city to remain healthy (p. 58).

Europe unfortunately never adapted Leonardo’s ideas for city planning.

However, centuries later another European, a Scot, would discover a

similar organic city planning in another civilization. In the planning of

the temple cities of South India, Patrick Geddes saw an integration of

the social life and cultural life cycle of the people that was unheard of in

the West. According to Leonardo, if one wants to change the course of

a river for human purposes then it should be done gently through such

sustainable technologies like small dams. He wrote: “A river, to be diverted

from one place to another, should be coaxed and not coerced

with violence” (p. 263).

In the planning of the

temple cities of South

India, Patrick Geddes

saw an integration of

the social life and

cultural life cycle of the

people that was

unheard of in the West.

An Indian mind cannot but remember the legend of young Sankara

singing and appealing the Purna River to change its course. Buried in

this legend of Sankara is perhaps a poetic invitation for the science of

sustainable water management.

In Learning from Leonardo (2013) Capra studies the notebooks of Leonardo,

and the book provides a new approach to the history of science.

With a detailed timeline of milestones in science from the time of Leonardo

(16th century) onwards into twentieth century, Capra purports to

show how the artist anticipated or even independently discovered

many of the later developments of science. According to Capra, Leonardo

developed an empirical method. The Church that considered Aristotelian

philosophy its theological bedrock viewed experimental science

with suspicion. But da Vinci broke with that tradition. Capra

claims:

According to Capra,

Leonardo developed an

empirical method. The

Church that considered

Aristotelian philosophy

its theological bedrock

viewed experimental

science with suspicion.

But da Vinci broke with

that tradition.

One hundred years before Galileo Galilei and Francis Bacon,

Leonardo single-handedly developed a new empirical

approach to science, involving the systematic observation of

nature, logical reasoning, and some mathematical formulations—

the main characteristics of what is known today as

the scientific method (p. 5).

In almost every field from mechanics to ecology – some of these disciplines

not even imagined at his time - Leonardo through observation,

experimentation and contemplation- had made a remarkable addition

to human knowledge. For example, Capra points out:

“Leonardo did not

pursue science and

engineering to

dominate nature, as

Francis Bacon would

advocate a century

later.”

Leonardo understood that these cycles of growth, decay,

and renewal are linked to the cycles of life and death of individual

organisms: Our life is made by the death of others. In

dead matter insensible life remains, which, reunited to the

stomachs of living beings, resumes sensual and intellectual

life. . . . Man and the animals are really the passage and conduit

of food (p. 282).

This remarkable insight according to Capra anticipates the concept of

food chains and food cycles that was developed by Charles Elton almost

four centuries later in 1927. Finally Capra distinguishes the basic

difference between the science of Leonardo and the science of Francis

Bacon: “Leonardo did not pursue science and engineering to dominate

nature, as Francis Bacon would advocate a century later.” Leonardo

had a ‘deep respect for life, a special compassion for animals, and great awe and reverence for nature’s complexity and abundance.’ If

this assessment of Leonardo by Capra makes the artist sound like a

Jain born in late medieval Italy, check this statement by Leonardo himself

“One who does not respect life does not deserve it.” Does it not reflect

the Jain dictum, ‘Live and let live?’

A LIFE IN HOLISTIC DIALOGUE

The most recent work of Dr. Capra is ‘A Systems View of Life – A Unified

Vision,’ coauthored with biochemist Pier Luigi Luisi. Published by

Cambridge University Press in 2014, the book is intended to serve as a

text book for students as well as the general reader who want to study

sustainable development integrating the physical, biological, cognitive,

ecological, and social dimensions. In the first part Capra explores the

rise of mechanistic world-view and in the second part the emergence

of systems thinking. The third part studies the new concept of life and

the fourth is about sustaining the web of life even as human societies

develop. The book is actually the encapsulation of the entire pilgrimage

of exploration that Capra undertook from the dance of Siva to the drawings

of Leonardo. The book is of immense relevance to India, a developing

nation with rural communities that are almost lost in the era of

globalization with a skewed playing field.

The book is actually the

encapsulation of the

entire pilgrimage of

exploration that Capra

undertook from the

dance of Siva to the

drawings of Leonardo.

The book is of immense

relevance to India, a

developing nation with

rural communities that

are almost lost in the

era of globalization

with a skewed playing

field.

With eco-conflicts set to escalate in the future and divisive forces try to

exploit them in both sides of the left-right fence, the worldview of Capra

provides a holistic alternative. Preservation of local knowledge systems,

creating networks of green innovators and eco-entrepreneurs at the local

level and globally networking them – all these are possibilities envisioned

in Capra’s worldview. While most leftwing eco-militants devalue

local spiritual and cultural elements, Capra has also brought out a powerful

reading of the Eastern spiritual symbols in the light of modern science.

For sustainable development, we ultimately need a drastic

change in the educational system. Capra, though not explicitly or perhaps

even intentionally, has provided a Dharmic framework, or at least

has sown the seeds for developing a broader inter-disciplinary science

of sustainable development with a Dharmic framework. Using his pioneering

works spanning a lifetime, each native culture and tradition can chart out a spiritual, holistic pathway to sustainable development. After all, the native traditions which

are struggling for their very survival on a planet dominated and to a significant extent devastated by

the supremacy and expansionism of Abrahamic values, can now knowledge-network themselves with

mutual spiritual validation to become important vehicles for the sustainable development and preservation

of the web of life. In this they may even transform the expansionist and monocultural tendencies

in the Abrahamic value system.