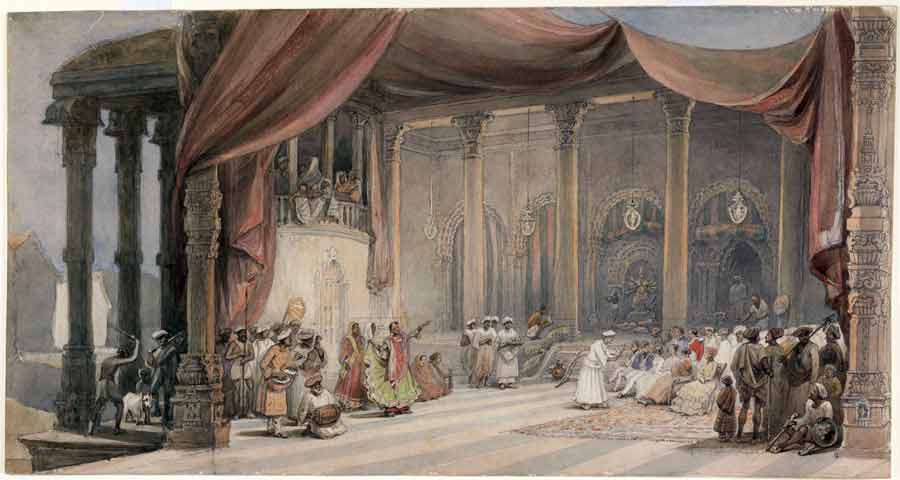

William Prinsep, Europeans being entertained by dancers and musicians in a splendid Indian house in Calcutta during Durga puja (1830s–1840s)

Editor’s Note:

This article presents some objects from the exhibition

“Puja and Piety: Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Art From the Indian Subcontinent”

at The Santa Barbara Museum of Art, April 17 – August 28, 2016. https://www.sbma.net/exhibitions/puja

It is rare to come across exhibitions that highlight the contextual uses of religious art from the Indian subcontinent. This is because the viewing

practice of art in the west privileges a decontextualized aesthetic enjoyment, effacing the ways in which religious objects are seen, used and enjoyed in

their native culture. The exhibition “Puja and Piety” Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Art from the Indian Subcontinent,” showing at the Santa Barbara Museum of

Art from April 17 to August 28, 2016 was conceptualized by the eminent curator of South Asian Art, Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, to remedy this lacuna. Dr. Pal

also wrote the introduction to the exhibition catalog (available at the museum store and on Amazon) to trace the history of ideas and practices relating to

these obejcts; and he invited four other scholars, including myself, to contribute to the catalog and exhibition. This article supplements the ideas

explored in the catalog. I’d like to acknowledge my debt to Dr. Pal for his expert suggestions and to Stephen Huyler and Susan Tai for permission to use

their images of objects in the exhibition.

Time-Bound Gods

In Hindu traditions, the divine who is permanent, changeless, infinite and eternal in his/her/its transcendental form, also becomes the cosmos and its

creatures and in these cosmic and individual forms, subjects himself/herself/itself to the processes of birth, growth and death. These processes themselves

are also eternal, through repeated rebirths and repetitions, in spite of change, growth or evolution. In Buddhism and Jainism, which originated in human

teachers, though there is no absolute divine, the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Trithankaras and Salakapurushas possess permanent ontological states, yet appear

in the changing time cycles, subject to transformations through karma and also assume time-bound forms.

Such an understanding of the temporal manifestations and rebirths of the divine is pervasive to the Indic popular understanding. Temporal appearances of

the gods and special “godly” beings[1] often pertain to the ebb and flow of the power (Shakti) of various

physical and psychological qualities related to days and nights, seasons and astrophysical conditions and can take the form of temporary pujas,

processions, festivals and performances. The major life events of godly beings, such as gurus, Jinas or Buddhas, particularly the historical Buddha,

Sakyamuni, may be commemorated each year through similar processions, ceremonies, festivals, rituals and performances. Hindu pujas are the most common of

these kinds of temporal worship, since the Hindu gods are both enshrined permanently in temples; and worshipped seasonally during special days reserved for

each of them, when their power on the changeful world (jagat) is greatest or on special days related to their mythologies or hagiographies. Both in the passage of such days of worship and the process of the ritual invoking life in the image

(pranapratistha), making offerings to it, receiving its “darshan” and its blessings (varada), being witness to the “departure” and participating in their

immersion (visarjan), the temporal processes of life are celebrated through the recognition of the self-subjection of the gods to time. Thus the images that are used in these processes are usually temporary images, seasonally fashioned of

temporary materials such as unbaked clay, wood or pith and returned to the elements after use.

Durga Idol Immersion (visarajan of deity) - River Hooghly - Baghbazar Ghat - Kolkata

Temporal Images

The earliest instances of such ideas in the use of images in India could have occurred during the times of the Indus Valley civilization (c. 2700 BCE –

1500 BCE), among whose remains a large number of small terracotta female figurines, considered to be Mother Goddesses have been found.

These figurines have been discovered almost universally in rubbish heaps or the remnant of storage tanks (Jarrige: 159), giving rise to the strong possibility that they were discards after ritual use. Such temporal enlivening of images may not be restricted to figurative

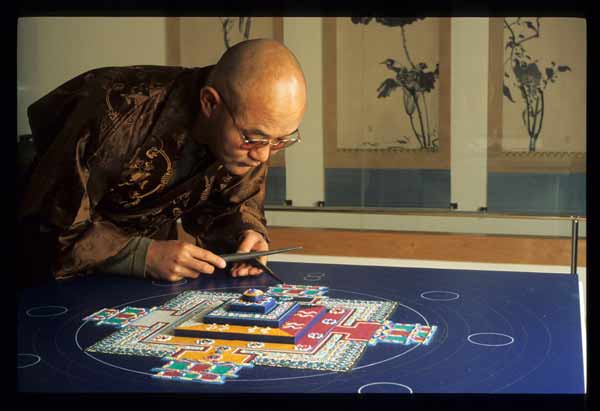

sculptures but may extend to symbolic objects or to significant “magic” diagrams (yantra) and formations, such as Vedic ritual altars. The most well known instances of the latter kind today are the Tibetan sand mandalas of Vajrayana

Buddhism, constructed painstakingly and elaborately, following complex and minute directions as part of the enlivening procedure, used in collective

contemplation accompanied with mantra recitation and ritual music, and destroyed at the end of the ritual.

Construction of Sand Mandala at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2002 © SBMA Archives

The development of cultic preferences for such temporal worship usually has a regional basis and distinct characteristics of material culture and ritual

practice. Among modern manifestations of temporal puja festivals, the Durga puja of Kolkata and the Ganesh Puja of Mumbai are well known populous regional

phenomena. Another class of temporal worship involving images are processions and chariot festivals. Perhaps the best known of these is the chariot

festival of Jagannath in Puri (from which the English term “juggernaut” derives); but such processions are common to several other regions, particularly in

S. India states such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka.

Chola Bronzes (Utsavamurtis)

From about the 11th c. in Chola territories of Tamil Nadu in South India, the influence of major deities of a city on its populations expanded

in scope with the establishment of massive royally sponsored temples, the incorporation of large numbers of people in the activities of the temple and the

seasonal processions of the temple deities through the town, paralleling royal visits.

Instead of temporary

images, Chola divine processions are conducted with bronze sculptures, known as utsavamurtis, some of which are kept in the sanctum sanctorum

(garbha griha), some in areas surrounding the circumambulation (pradakshina) path and some in storage in the temple. Many of them are available within the

temple for darshan throughout the year. These are paraded at the time of the processional festivals, carried in chariots or on platforms or palanquins on

the shoulders of devotees. While bronze casting using a lost wax process has a long history in Tamil Nadu, the Chola bronzes meant for processions

developed an elegant and elite sophistication based on what has sometimes been referred to as an “Indian classicism.” This canon can be traced to the

Northern Indian Gupta court of the 5th c. C.E. and its antecedent regional variants in Maharashtra, Karnataka and Northern Tamil Nadu. Over

time, these images may become damaged or lose their clear definition and become unrecognizable. They are then reshaped or melted and recast, in keeping

with the idea of the rebirth of time-bound gods.

Processional Image Representing Parvati, the Spouse of Shiva, India, Tamil Nadu,

14th century Bronze, Lent by Natalia and Michael Howe, Cat. 86

Uma (Parvati)

The exhibition features two such processional images, one 14th c. bronze image of Uma (also known as Parvati) (86), the spouse of Shiva and a 13 th c. copper alloy statue of a Shaiva devotee (Nayanar), Chandesvara (114). The Uma image stands on a platform held over an inverted lotus, with

a characteristic stylish sway of her left hip which supports the elbow of her extended left arm, a slightly flexed right leg, an upright torso with high

full breasts and her right hand with delicately modeled fingers closing in as if to hold the invisible stem of a lotus flower. She is adorned with a tall

peaked (shikhara) crown, large heavy earrings, a number of necklaces, a waistband, armlets, anklets and bangles. She wears a sacred thread (upavita)

falling over her left shoulder, between her breasts and over the tightly muscled curvature of her small belly before circling to her back from her right

hip, and a see-through lower garment covering her legs. She has carefully chiseled aristocratic aquiline features and the base holding her and her lotus

platform has a set of four lugs for lifting and fitting onto the chariot using rods. As she has her independent base, she could be carried in her own chariot

or on Lord Shiva’s chariot, beside him on his left, but in either case she would belong to the procession ensemble of Shiva.

Processional Image of Chandeshvara, a Shaiva Saint,

India, Tamil Nadu, 13th century,

Copper alloy, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of Lewis Bloom, Cat. 114

Chandesvara

Shiva processions in Chola and post-Chola period Tamil Nadu, upto and including our times, have also often featured subsidiary chariots with the Tamil

Shaiva saints (Nyanmars). Though traditionally there are 63 nyanmars, a temple procession may feature only some of these. Among the most popular of these

is the devotee Chandesvara, often depicted with an axe. A particularly elegant example is to be seen in the exhibition, where Chandesvara, a highly

ornamented young boy wearing a crown over his coiled hair (jatamukuta), a large number of necklaces around his neck, large earrings, armlets, anklets, a

waistband and many bracelets, stands with a sway to his right hip and a slight flexion to his left leg. His hands are folded in devotion (Anjali mudra) and

between their palms is pressed a small flower garland. His features are serene, with large almond shaped eyes, aquiline nose and small relaxed lips, framed

by the base of his coiffed hair and his locks falling over his shoulders. He stands on a lotus pedestal, with perforations in its base to accommodate rods

for lifting and arranging on the chariot. Chandesvara’s opulent appearance here is unusual, and highlights his pre-eminent position as guardian of Shiva’s

storehouse and receiver of his offerings. The garland between his hands represents a gift granted to him by Shiva and Parvati after his heroic act in

striking his father’s leg for having kicked at a sand linga which Chandeshvara was worshipping with milk.

Procession with Image of Vishnu Seated on Garuda

India, Karnataka, early 19th century,

Color and gold on paper,

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of Pratapaditya and Chitra Pal,

Cat. 20

Wooden Chariots

Wooden chariots for these processions are maintained in temples and are repaired, decorated and painted each year, and sometimes rebuilt. The tradition of

wooden chariots and processional objects has its origins in hoary antiquity, as may be learned from literary evidence, but due to the fragile nature of

wood in its subjection to weather and human use, most examples are of more recent origin. In this exhibition, this genre has been represented in ample

measure, for the first time in the U.S. Depending on the importance of the rider of the chariot, each chariot is fitted with decorated elements and wooden

sculptures. During the procession, the chariots and their riders are richly dressed in dyed, printed and appliqued textiles, and covered with many jewels

and fragrant and colorful garlands. In this exhibition, we have 3 wooden statues which would adorn such chariots or be carried separately during the

procession and some architectural elements belonging to procession chariots.

Processional Image of Vishnu Riding Garuda,

India, Tamil Nadu, 18th century,

Wood with traces of gesso, polychrome enamels and glass, Lent by Narendra and Rita Parson,

Cat.19

Garuda and Vishnu

The most spectacular of these is the close to 5 feet wooden cart with Garuda and Vishnu. The unusual scaling of the image makes the Garuda much larger than

the Vishnu, seated in his characteristic kneeling pose with one leg lifted and bent ahead and wings outspread, ready to fly at the beckoning of his Lord.

His wings and sash have striped incising, as of feathers and corded rope, respectively, and one can see the long back feathers resting behind him. A

serpent (Naga), symbol of Vishnu’s reptilian bed and Garuda’s enemy, slides over his right neck. His belly is relaxed and extended in the style of early

(pre-4th c.) yakshas. His features are rounded, his eyes beady and his nose pointed like a bird’s beak. He wears a pointed crown, some jewelry

and a sacred thread (upavita). His two hands are raised to provide pedestals for the feet of Vishnu, who sits on a small throne atop a platform that rests

on Garuda’s shoulders.

Vishnu, as mentioned earlier, is smaller than Garuda, but exquisitely depicted, framed by a polychrome enamel M shaped surround, with a post-Pallava yali

derived Kirtimukha or Kalamakara, hybrid spirit of Time, who eats away at everything. Even Vishnu is subject to him, or rather accepts his subjection, only

to demonstrate his mastery by dint of His supreme power. His face is a simply and finely etched living mask of power. In his two outer hands he holds the

conch and discus and his inner hands bestow fearlessness (abhaya) and blessings (varada). He is harnessed with jewels and his crown is surrounded by a

double halo with the remnants of gesso and glass inlay.

This ensemble, resting as it does, on a cart frame, could either have been carried by itself on human shoulders or caparisoned animal back, or as part of a

chariot’s decorations. Given its content and the power of its depiction, the only chariot it could have been part of would be the chief chariot in a Vishnu

procession. There was clearly a lot of polychrome color to it, most of which has disappeared.

Miniature Shrine with the Figure of Goddess Rati Riding a Gander (Hamsa)

From a Temple Chariot(?),

India, Tamil Nadu, 18th century,

Wood, Lent by Pratapaditya and Chitra Pal, Cat. 107

Rati

Another interesting chariot decoration sculpture is a miniature wooden shrine dedicated to the goddess Rati or Lust, spouse of Kama, the Indian Cupid. Such

an element must have belonged to a Shiva procession, perhaps as part of the main Shiva chariot. There it would bring to mind an episode from the story

cycle of the marriage of Shiva and Parvati. Kama, charged by the gods, inflames the meditating Shiva’s heart with his arrow of desire and Shiva, opening

his third eye of fire, burns Kama to ash. Rati plays a part in this story, beseeching Shiva to let her husband live on as a subtly and materially

unembodied existence. In the popular imagination, Rati’s erotic spirit dominates and in the sculpture in our exhibition, she is depicted as the wielder of

the arrow of Lust. She rides the gander, her vehicle (vahana) provocatively but with miraculous physical grace, as one can come to expect from the advanced

visual vocabulary of Bharata Natyam. There is a wild abandon to her body as the force within her compels her to loose the arrow. Her hair swings loose like

a money’s tail, another association with instinctive animal grace, while the muscular splay of her legs is indicative of a rippling gyration. The attitude

of her face and the intense power of her eyes make her a causeless primordial cosmic power. She and her vahana are tighly framed through an imagination

that wishes to maximize the occupation of space, filling and overflowing the shrine of her chariot-temple, which includes fractal versions of itself in the

faux devakoshtas above the frame of the shrine. Two small wheels separated cleverly by an unfolding lotus complete the fractal replication of the chariot.

Strut from a Chariot with the Mythical Saint Agastyamuni.

Agastyamuni is said to have introduced Vedic culture to south India.

India, Tamil Nadu, 18th–19th century,

Wood,

Lent by Narendra and Rita Parson,

Cat.110

Agastya

Also related to Shiva processions is the Vedic rishi Agastya, who is supposed to be the first North Indian sage who traveled to the South and settled

permanently there. Agastya became a popular figure in Tamil Nadu from Chola times, and due to Chola influence in Southeast Asia, a cult of Agastya assumed

enormous proportions in Java, Indonesia, where tmeples and images of Agastya are profuse. In the complex braiding of Shaiva cults with Vedic ones in Tamil

South India, Shiva became the Lord of Agastya, Agastyeswara. Hence it is common to see a pot-bellied and long bearded coiffed jatadhari male figure with a

pot in his left hand and the right hand in fearlessness gesture (abhaya hasta) existing as relief on the outer pillars of Shiva chariots. In this

exhibition, we have one of these pillars showing the Vedic rishi Agastya. Agastya carries the air of Brahma, the Brahmanical god, representing the wind and

water of creation in his belly and his pitcher respectively. Agastya had the reputation of swallowing up the Indian ocean from his waterpot. He is depicted

wearing a decorated dhoti, bestowing fearlessness (abhaya hasta) with his right hand. He wears necklaces and armlets of beads or seeds, perhaps rudraksha.

He has a smiling benign and peaceful face, a more earthy type of the ideal that expressed itself as the Buddha of the Gupta period in North India (4 th-6th c. C.E.). In our example, the abhaya hand is reddened due to smearing with sindoor by women, because Agastya is also seen as a

fertility bestowing figure.

Architectural Fragment with Riders and Mythical Animals, India,

Tamil Nadu, Chettinad, 18th century,

Wood, Lent by Narendra and Rita Parson, Cat. 113

Riders with Mythical Animals

Among architectural elements of chariots, we have in this exhibition, a door with Naga snakes as protectors of the temple (112).

Nagas or snake gods, based on the hooded Indian cobra, appear in Hinduism as supernatural demigods that live in submarine regions below the earth. They

symbolize the potential energy of nature, at the cosmic and individual levels. In Tantra, they are visualized as the coiled energy, kundalini, at the base

of the spine. At the cosmic level, Vishnu sleeps on the infinite coils of the serpent Ananta and Shiva is ornamented with nagas and known as their lord

(Nagaswami).

Parts of a Doorframe or a Temple Chariot with Naga (Serpent) Protectors,

India, Tamil Nadu or Kerala, 18th century, Wood with polychrome,

Lent by Narendra and Rita Parson, Cat. 112

Intertwined male and female serpent couples (naga-nagini) are seen as fertility figures and guardians. Hence, they are often carved on doors to the sanctum

of temples. This door could have been a temple door or from a processional chariot dedicated to Shiva, Vishnu or the Lord of Snakes, Nagaraja. The figure

at the left top has a beak and hence, could be Garuda, the mount of Vishnu and enemy of nagas. His presence on the door makes it most probable that this

was a door to a Vishnu shrine. The rest of the figures are either male nagas (marked by a mustache) or female naginis. Though powerful and ferocious, they

all wear smiles, denoting their happiness at serving their divine Lord.

Headpiece Used on Ceremonial Occasions with the Mask Representing Thira, a form of goddess Kali in Kerala,

Surrounded by images of Gajalakshmi and musicians, India, Kerala,

19th century

Wood panels, string, Lent by Narendra and Rita Parson, Cat. 28

Performances

Notable in this genre of temporal gods, must be considered folk performances of mythological legends, particularly in regional traditions where some means

of estrangement from everyday reality are used to bring the audience closer to an altered state of consciousness, where they may have a darshan experience

of a deity through the actors. The face-painting and masked performance traditions of Kerala afford powerful examples of this

genre. In this exhibition, this tradition is invoked through the presence of a wooden head-piece depicting a devouring head like that of the kirtimukha,

but representing Thira, a regional form of the fierce goddess Kali. This is worn above the head during a festive season in the

South Malabar region of Kerala. In performance, she is paired with Poothan, Shiva’s lieutenant, to perform ritualistic dances in temples and around town.

To the beat of a drummer, they dance to ward off evil spirits and to wish the townspeople happiness and prosperity twice a year, especially during the Pooram festival season between December and May.

The headpiece is an assemblage of wooden panels, with musicisns in profile flanking the Thira face on both sides and an image of Lakshmi seated in lotus

posture (padmasana) with lotuses in her two hands and flanked by two elephants who lustrate her with inverted pitchers of the elixir of immortality

(amrita). This ancient form of Lakshmi, called Gajalakshmi, is a great symbol of auspiciousness and highlights the benificient and compassionate nature of

Kali for his devotees.

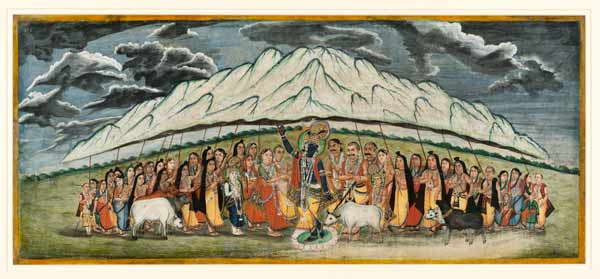

Krishna Holding up Mount Govardhana to Protect the Citizens and Bovines of Brindavan from a Fierce Storm,

Illustration of the legend for the origins of the Shrinathji image of Nathdvara

and the Vallabhacharya sect of Vaishnava devotion (cf. # 57, 58),

India, Rajasthan, Nathdvara, late 19th century, Opaque watercolor and gold on paper,

Lent by Narendra and Rita Parson, Cat. 55

Changing Sets

Though the worshipped images in temples are considered permanent, since they have taken residence on earth, they are also subject to the diurnal and

seasonal changes of the earth. Most temples open at 4am, a time known as brahma muhurta, when the deity awakes. Pujas done through the day are related to

the daily activities of the god. During the afternoon, the temple doors close for the deity to have his or her siesta, opening again in the evening with

pujas appropriate to the activities of the evening. At night, the deity goes to sleep. In many temples, the idols of deities are dressed and fed according

to the time of day and the season; and in temples, where the deity is offered music as one of his/her royal enjoyments (rajopachara), ragas appropriate to

the time of day are sung.

One temple which treats the daily and seasonal behaviors of Krishna more literally than most, is the temple of Srinathji at Nathadwara in Rajasthan. The

founding myth of this temple is itself a good case of migrations undertaken by and surrounding permanent icons. Srinathji is in the form of boy Krishna

lifting the Govardhan Hill with his left small finger. The story refers to a pastoral hero-cult legend

of Krishna’s victory over the Vedic god Indra. It was said that Indra demanded offerings from the cowherding hill people of Mathura. The boy Krishna taught

the people to worship the hill on which they had settled, by name Govardhan (literally “cow-nourishment”), as a manifestation of God. Indra sent a deluge

to punish the villagers for shifting their allegiance and neglecting him; and Krishna picked up the mountain with his left little finger and held it like

an umbrella to protect the villagers from the deluge. To this local myth, a practice had become traditional by the 15th c. This consisted of

offering a mound of rice, called Annakut (literally “rice-peak”), to Krishna on the day commemorating this event. One may speculate that Krishna’s act of

taming the waters of heaven and drawing the worship of the villagers to the mountain may have resulted in the controlled fertilization of the earth and the

production of abundanct rice.

Sometime in the 14th c.., the legend arose of a black stone idol with the left hand raised appearing from a hole in the Govardhan hill. Carved

in bas-relief on a single piece of black marble, and carrying an attitude as of lifting a mountain, it was designated a self-born (swayambhu) icon of

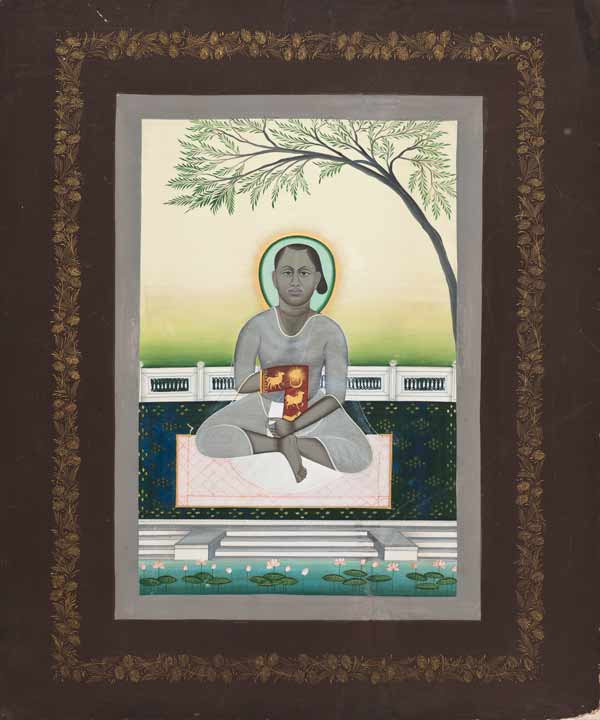

Krishna the lifter of Govardhan, and worshipped as such by Vaishnavs of the region. In the 15th c., the Andhra saint, Vallabhacharya, was

visited by the idol in dream and asked to move to Govardhan Hill to worship him. Vallabhacharya founded his sect of Krishna worship called Pushti Marga,

with this image at its center. Vallabhacharya is credited with establishing the form of worship of the deity, which treats him as a living child, attended

with daily functions, like bathing, dressing, taking meals and resting at regular intervals, caring for him as baby Krishna’s foster-mother Yashodha would

have treated him. Vallabhacharya’s son, Vitthal Nathji (also known as Gusainji) named the deity Srinathji and added special feasts & meals (bhog),

music (raga) and elaborate dressing and adulatory rituals (sringar) into the daily services (seva) of Shrinathji. The genealogical descendents (kul) of

Vallabhacharya continue to be the main priests of Srinathji and a tradition of painting portraits of these priests has developed around the cult of the

deity.

Vaishnava Saint Vallabhacharya (active 1481–1533), Founder of the eponymous sect,

India, Rajasthan, Nathdvara, early 20th century, Watercolor and gold on paper,

Lent by Narendra and Rita Parson, Cat. 116

In the 17th c., fearing destruction from the iconoclastic Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, the idol was moved in a chariot further west. When the

chariot came to the village of Sihad in Mewar, Rajasthan, its wheels sank in the ground and would not move. Krishna then gave an indication to the priests

that he wished to stay there and a temple was erected there under the protection of Rana Raj Singh of Mewar. This temple at Nathadwara is popularly called Shrinathji ki Haveli (House of Shrinathji) because it is designed to function as a wealthy medieval household and includes a number of specialized

spaces, such as a drawing room (Baithak), a functional kitchen (Rasoighar), a jewellery chamber (Gahnaghar), a treasury (Kharcha bhandaar), store rooms for

flowers (Phoolghar), milk (Doodhghar), sugar (Mishrighar), sweetmeats (Pedaghar) and betel (Paanghar), a gold and silver grinding wheel (Chakki), a stable

for horses (Ashvashala), and the original chariot in which Shrinathji was brought, for his movement. The Srinathji cult today has spread to several places

worldwide, with their own versions of temples for Shrinathji. In the US, there are at least eight Srinathji temples.

Apart from the daily dressing, beautifying (sringar) and adoration (arati) with flowers, incense, food and fly-whisk of the idol of Shrinathji, occasions

of popular attendance include the festivities related to special occasions and seasonal events in the life of Krishna. Of these, Krishna’s lifting of Mount

Govardhan naturally takes the place of prime prominence and is celebrated as Govardhan Puja or Annakut in winter on the fourth day after Diwali. Other

important occasions include the birth of Krishna (Janmashtami), the victory of Rama over Ravana (Dussera), Krishna’s dance circle with the Gopis (Rasa

Lila), the Spring festival of color (Holi or Dolotsava), the honoring of River Yamuna (Yamuna Dashami) and Krishna’s final departure from Vrindavan to

Mathura (Ratha Yatra). Apart from these, there are seasonal festivals. On each of these occasions, Srinathji is dressed is special clothes and ornaments

(vesha) and surrounded by objects appropriate to the occasion. The form of the ritual is also designed according to the occasion.

Picchvais

A unique form of visual culture connected with all these events is the painted cloth backdrop which is hung behind Srinathji. This is called “picchwai”

(literally “backdrop”) and is painted in a variety of styles, depending on the artists of Nathadwara and their family traditions. For each occasion, an

appropriate picchwai is hung like a theatrical set for Srinathji to perform in front of. To attendees, these backdrops enhance the visual ambience and

foster the sense of being present at the actual play (lila/kreeda) of Krishna designated by the occasion. In this exhibition we carry a number of these

picchvais.

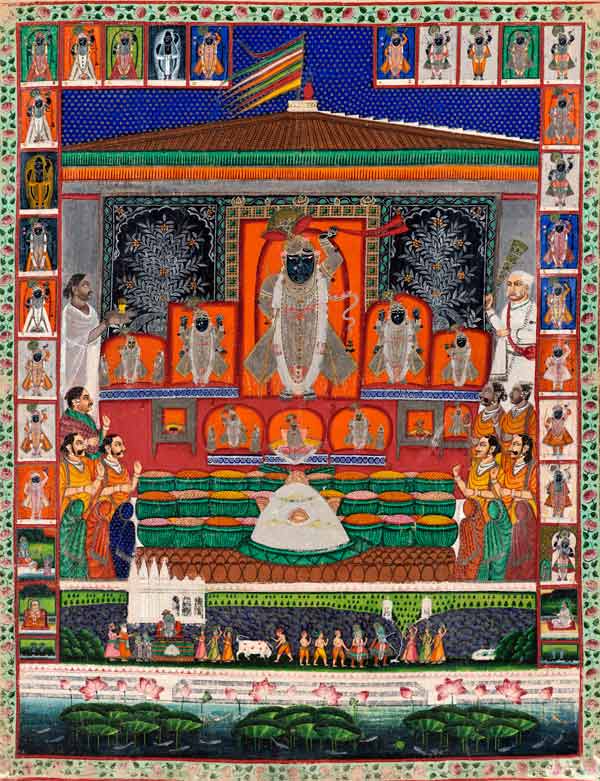

Pichhvai Showing Food Offering to Shrinathji at the Annakut (Mountain of Food) Festival,

India, Rajasthan, late 19th–early 20th century, Ink and color with gold and silver on cotton,

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of James and Susheila Goodwin and Museum Purchase

with funds provided by General Acquisitions Fund, Cat. 57

Annakut

As mentioned above Srinathji embodies the form of Krishna when he lifted the Govardhan mountain. Since this is the incident celebrated as Annakut, it is

not surprising that Annakut is the most important occasion at Nathadwara. Here we have a magnificent picchwai meant for this occasion. This painting on cotton cloth, made in the late 19th or early 20th c., demonstrates a

unique combination of naturalistic and decorative painting traditions. Whereas the formal composition and depictions of the idols, architecture, foliage

and narrative elements follow a flat decorative convention, the figures of the priests adulating Srinathji, though formally positioned and shown in

profile, have faces that are modeled sensitively and naturalistically to be recognizable as portraits.

The border of the painting is made up of ornamented creepers with roses. Within this, we see the river Yamuna with somewhat naturalistic lotuses at the

bottom and an arrangement of small squares showing Srinathji dressed for various important occasions from the bright and dark phases of the lunar months.

At the bottom right and left of these squares respectively, we see the founder Vallabhacharya and his son, Gusainji seated, figures that repeat as the main

priests to left and right respectively, Vallabhacharya with adulating Srinathji with a flame (arati), while Gusainji holds a fly-whisk of peacock feathers,

meant also to ward off evil forces because of its myriad “eyes.” Below these two main priests are other lineage holders of their clan (kul) and the women

with heads covered in sarees.

Beside and below the large statue of Srinathji are other important Pushti marga idols of Krishna in stone and bronze, including the aniconic shalagram

image at the right lower corner of Srinathji. Symmetrically below Srinathji is a large white mound of rice with four large ear shaped sweets stuck in it,

baskets of sweets all around and small pitchers of milk and curd below. Above the stylized roof of the building a multicolored pennant flies in a

ultramarine sky dotted with decorative stars; while below, one sees a continuous narrative of Krishna, Balaram and their cowherd friends in Gokula with the

lotus laden Yamuna below them and the Govardhan mountain and green swards behind them. To the viewer’s left, they are seen participating in “Daan Lila,”

where Krishna stopped the milkmaids to ask them for the tax of milk and butter which they were carrying on their heads to the market; and to the right, the

same figures are seen bringing sweets to adulate Srinathji for the Annakut festival. The symmetric and symbolic composition in vivid contrasting colors

magnetizes the eye with its unique aesthetic qualities, evoking bhakti or devotion.

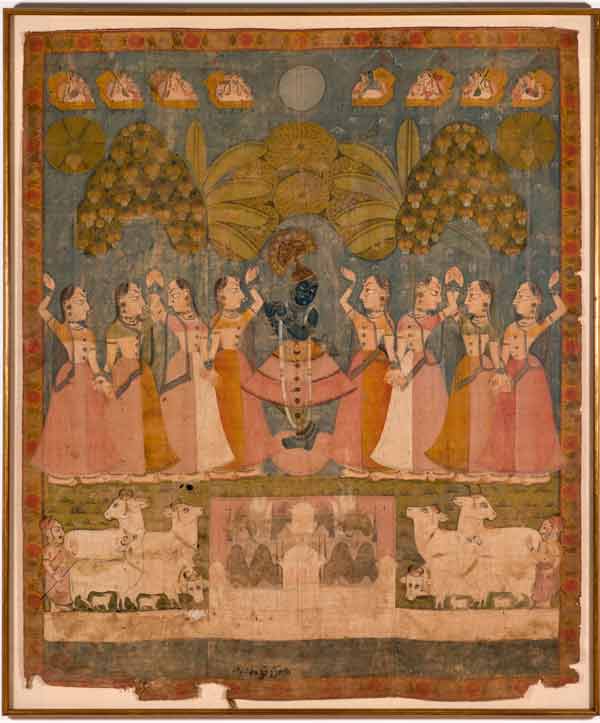

Temple Hanging with Cowherd Girls Adoring Krishna and the Festival of the Autumn Full Moon (Sharat Purnima),

India, Rajasthan, early 19th century, Ink and color on cotton, Lent by Julia Emerson, Cat. 58

Sharat Purnima

Sharat Purnima is the festival of the autumnal full moon, a time when Krishna danced his most enchanting and mystical dance with the gopis (milkmaids) of

Vraja. Here, we feature two picchvais for this occasion. In the earlier one, from the early 19th c., we find the Krishna as a flutist with

flaring skirt surrounded symmetrically by the gopis in profile with their hands raised in a manner matching the upraised hand of Srinathji, as if readying

themselves to hold it. Here the image of Krishna is not that of Srinathji but of Gokulchandramaji,

another black stone idol of Krishna belonging to Nathadwara. Behind them, stylized foliage following Rajput conventions evoke the forest where Krishna

danced with the gopis and above these, to two sides of the round full moon, Brahma and Shiva sit in “sky-chairs,” enjoying their balcony view of the dance

with their consorts, Saraswati and Parvati respectively, while flanked by other gods playing musical instruments. Below Krishna, one may see the Nathadwara

haveli (house) surrounded by Krishna’s cowherd friends leading their cows to the haveli. Unlike the later picchvai of Annakut or the other Sharat Purnima

picchvai, the figures are not shown with any depth modeling and are entirely flat, in profile, with stylized features resembling Krishna. The

characteristic feature here are the long slanting eyes, a convention also found in the popular paintings of Kishangarh (according to Amit Ambalal, the

Kishangarh convention was borrowed from Nathadwara). The charm of this painting lies in its pastel colors and rhythmic decorative composition.

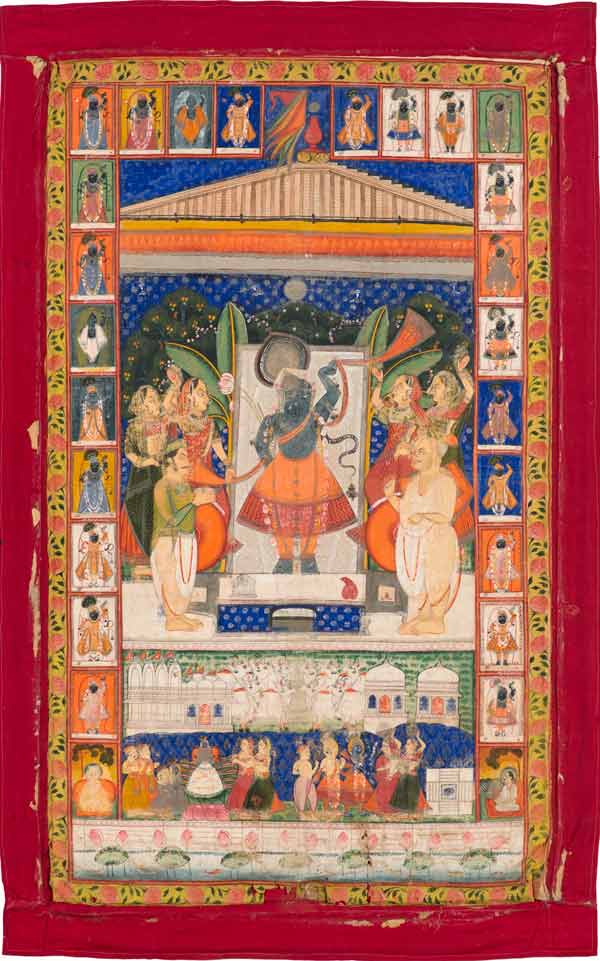

Temple Hanging Showing the Worship of Srinathji

The other Sharat Purnima picchvai follows conventions very similar to the Annakut picchvai and can be dated to around the same period (late 19th

c.) and may have been painted by the same hand. Like the Annakut image, it has a

floral outer border and an inner border whose sides and top depict the twenty-four important dress-presentations (vesha) of Srinathji from the bright and

dark phases of the twelve lunar months, with Vallabhacharya and his younger son Gusainji making up the bottom right and left figures respectively; while

the bottom part of the picchvai depicts the same scene of the river Yamuna with lotuses by whose side Krishna, Balaram and their cowherd friends and gopis

enact the daan lila to the left and the annakut festival to the right. Again as with the Annakut picchvai, an ultramarine sky studded with ornamental stars

is seen behind Srinathji and the gopis, along with a very similar pavilion roof flying a multicolored pennat. Two Nathadwara priests do the adulation

(arati) of Srinathji, who is flanked by the dancing gopis. Krishna here is not the flute playing image but the Srinathji idol and the features of the

priests and gopis are marked by individualized portraiture and naturalistic depth modeling. The aesthetic values of this image are very similar to that of

the Annakut painting.

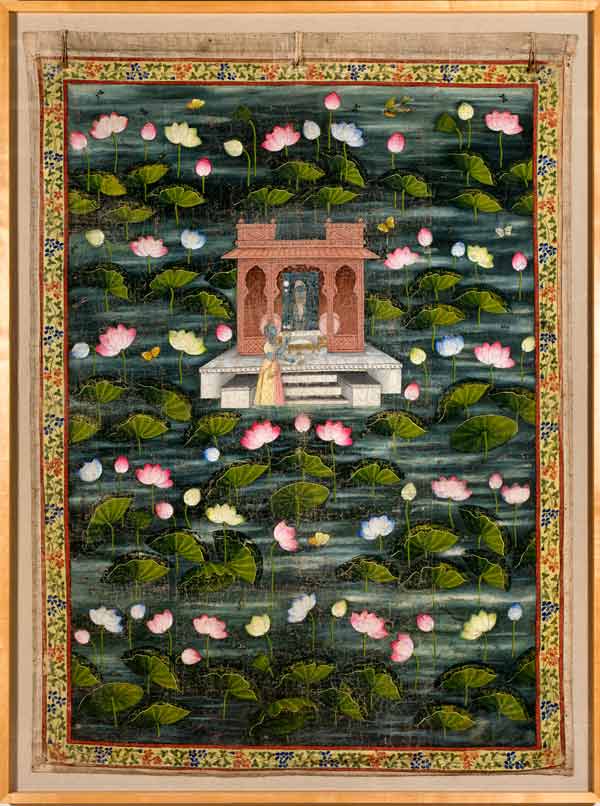

Temple Hanging Depicting Water Festival (Jal Vihar), with Floating Shrine in a Lotus-filled Lake, India,

Rajasthan, Kishangarh(?), early 20th century, Ink and color on cotton, Lent by Julia Emerson, Cat. 59

Jal Vihara

In the summer months, Srinathji is frequently depicted enjoying the cool waters of the River Yaumna. Such picchvais are known as Jal Vihara (play in

water), also called kamalan ki picchvai (backdrop of lotuses), due to the prominent depiction of lotuses in these paintings. The scene is often poetized in

reverse, with Krishna being compared to a fragrant lotus flower and the lotuses thought of as the gopis surrounding him like bees. In this example from the

early 20th c., we find, once more an attractive and unique blending of the decorative and the naturalistic [Image: Temple Hanging depicting

Water festival…]. It is a night scene, with the moonlight gleaming on the waters of the Yamuna and the lotuses and lotus petals depicted with

three-dimensional modeling and chiaroscuro effects. The architecture of the water pavilion is also shown with three-dimensional perspective, but Srinathji

within the pavilion and the dark lady in front of him with lotuses in her hands are stylized and flat. Srinathji almost blends into the night with his

black color and wears only ornaments and a light cloth on his bare body. Such a mystical exposure of the body is reserved for the most private darshan of

the dark lady in the depth of the night. The fortunate recipient of this darshan and intimate play at this time and season is not Radha or the gopis but

the personified River Yamuna, who has brought lotuses to worship her lord. The multicolored lotuses and the gleaming naturalistic waters of the night make

a beautiful mystical backdrop (picchvai) for this special paly of Srinathji.