Editor’s Note

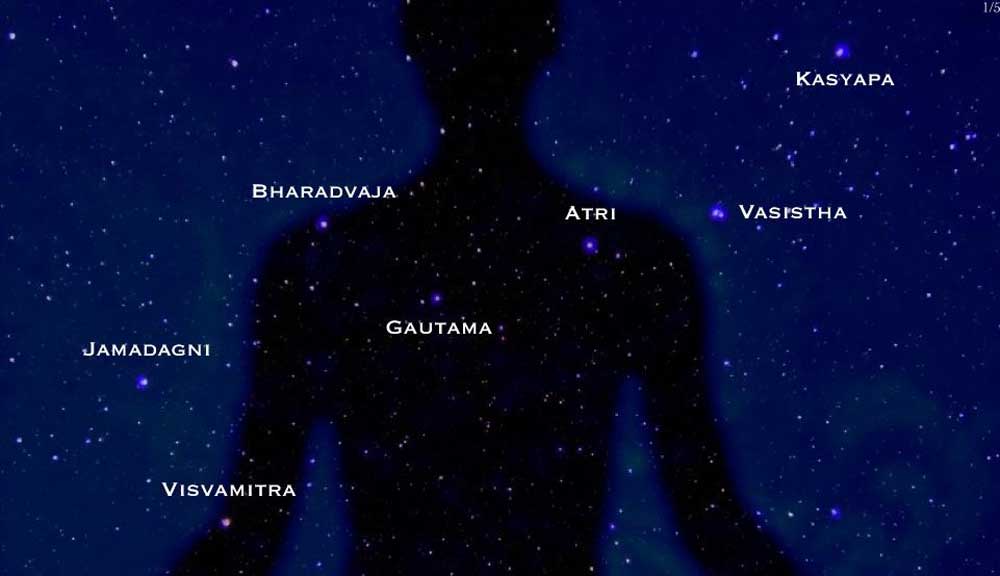

The seven stars comprising the ‘Big Dipper’ are considered the self-reflexive eyes of the seven Seers of the Veda. In Sanskrit, this cluster of stars is called Rksa, the abode of the Seers. The Seer Vāsiṣṭha is a legendary figure who has been visioned and heard by mystics, and in a shamanic culture such as India this is not unusual. The Yoga Vāsiṣṭha is a very important text in the sacred tradition of India and has been part of its vibrant oral history for a very long time. The teaching of Yoga by Sage Vāsiṣṭha is considered by historians to have been set to writing more than a thousand years ago.

The seven Seers circle the pole star, the central axis of the universe relative to our place in our era. The Sapta Rishi from their vantage point continually see the Veda, for what is the Veda but the rising of the (inner) Sun.

Brāhman! In every manvantara, when the sequence of the world is reversed and the structure is altered and the wise people have passed away, I have different friends, different relatives, different and new servants, and different habitations.

YV, 6.I.22.37-38

Imagine yourself awakening one morning, preparing your breakfast, only to see yourself performing these actions in a parallel universe. These worlds can then be seen to collapse upon themselves, nesting in ever-smaller frames, until you recognize that it is you that is moving, one speck of dust within the faint sheen of dust capturing the sunlight in the corner of the house.

What exactly is real? What is the nature of reality? What is the purpose of any particular life? These are some of the questions that the YogaVāsiṣṭha (YV) explores in tales that are epic in size and minute in their detailed storytelling, interlocking tales of kings, sages, and people from the entire spectrum of occupations.

In an era of contemporary identity politics, selfproclaimed enlightened masters, and the invention of bizarre practices under the title of yoga, it has become necessary to re-examine the traditions themselves and the texts that have been classically dedicated to establishing yoga. We need to go back to the sources of this global phenomenon that has come to be known as yoga and read the practices and philosophies that once were archaic and reserved for very few practitioners and bring them to global discourse for public awareness. My effort here is to offer a small introduction to one of these foundational texts, the Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha.

The Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha is a synthesis of the Hindu and Buddhist yogic traditions and philosophies. While placed in the context of a discourse between a prince wanting to recognize the nature of reality and questioning an enlightened master, the text borrows from a wide range of Hindu and Buddhist literature.

The style of the book is like that of the storytelling found in the Rāmāyaṇa, and the text itself is deeply philosophical in nature. Although the text borrows ideas from Pantañjali to Vasubandhu, the unifying philosophy is closer to the Advaita of Śaṅkara. Due to subtle differences in teachings and philosophy, it took time for the mainstream Advaita to acknowledge the text as significant to its philosophy, and the text has only been frequently cited by mainstream Advaitin scholars in school of Śaṅkara after around the 15th century. Setting the philosophical premises aside, the text is exemplary poetry, and the author – one Vālmīki – is impeccable in his use of meter, choice of words, application of metaphors and metonymy, and the overall application of suggested meaning to convey the message. The text can be read as a mythical narrative, poetry of the highest quality, a text on philosophy, and as a manual for a yogic practice.

Traditionally, the Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha is considered one of the Rāmāyaṇas and the authorship is attributed to Vālmīki. The text is staged in the platform of a dialogue between the protagonist Rāma and his enlightened master Vāsiṣṭha who then re-tells his conversations to the ṛṣī Bharadvājā, one of seven seers to whom the Vedas are attributed. Historically, the Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha could have been compiled between the 9th Century and 12th Century; however, the text was not always known by that name. An earlier iteration of YV is known as Mokṣopāya, and a summarized version of the text, the Laghu YogaVāsiṣṭha, is more popular among the scholars and practitioners than the lengthy text that is divided in six sections consists of 32,000 verses, four times the size of Homer’s Illiad.

The text begins with Rāma the prince recognizing the dissatisfactory nature of the world, and finding himself in front of the sage, Vasiṣṭha.

The most external layer of the text presents teachings of the sages from Vedic times to tales of the characters from the Rāmayana. The inner layer of the text weaves multiple stories as a means for Vasiṣṭha to instruct Rāma. The essential core of the text is the monistic philosophy of pure consciousness giving rise to the diverse experiences in the world. The text also maintains that the intrinsic nature of consciousness is never polluted, albeit being given the appearance of bondage. The objective of all the stories is to teach Rāma that in consciousness itself, no deviation as such has ever occurred, no world external to consciousness has ever come into being, and no bondage is ever possible. All the narratives aim to reveal the eternally liberated nature of the self that is manifest as if bound in the world, constituting a finite reality in terms of the external world and the inner subject.

DISPASSION

As the text unfolds with the frustration of Rāma, the first section is rightfully identified as Vairāgya (dispassion), and the 33 chapters in this section highlight the ephemeral nature of the world. The text, however, is meticulous in teaching that human endeavor is central to recognizing reality, directly countering and even ridiculing the fatalists. The second section, Mumukṣu Vyavahāra, consists of 20 chapters and identifies the conduct that is required for the individual seeking liberation. These two early sections lack stories that can be read as philosophical. Instead, they primarily contextualize what is to subsequently unfold, and in this regard merely lay the foundation for the philosophy beginning in the next section on origination.

CONSCIOUSNESS AS PRIMARY

The third section, called Utpatti or origination, has 122 chapters and is significant both for the stories themselves and the philosophy embedded within them. The most important stories in this section include that of Līlā and King Padma, the story of a demoness Karkaṭī, and the story of king Lavaṇa who in his hypnotic state wakes up in a different identity and when he returns to being the king, questions his very subjective state. Although the stage within which these narratives are woven appears to support some form of illusionism, the text is clear that there is an unchanging essential core of pure consciousness manifest in multiple forms.

Next is the section on Stithi or sustenance, with a total of 62 chapters. Prominent are the stories of Vāyu and Śukra, of Śambara a demon, and of Dāsura. Philosophically this section addresses the nature of mind, different states of consciousness such as waking, dreaming, and deep sleep, the reality of time and space, the scope and function of ignorance, the nature of the self, and the issue of morality in light of subjective illusionism.

The fifth section concerns Upaśama or controlling the senses. The highlight of this section is the Siddha Gītā, where Vasiṣṭha narrates to Rāma the instructions given by the enlightened siddhas to King Janaka. This section includes the stories of Pāvana, of Bali, of Prahlāda, Gādhi, Uddālaka, the conversation of Suraghu, and the story of Bhāsa and Vilāsa. There are in total 93 chapters in this section.

YOGIC REALIZATION

The final section on Nirvāṇa is divided into two, with the first part containing 128 chapters while the last has 216 chapters. The highlights of the first section are the stories of Bhuśuṇḍa, Arjuna, Jīvaṭa, Śikhidvaja and Cuḍālā, and Kaca. In this section, there is also a conversation on the seven stages of yogic realization and reality as perceived by the enlightened beings. The very first narrative in this section reveals the central premise of the book, that there are two fundamentally different upāyas or approaches to liberation: one, the practice that pursues supernatural powers while integrating self-realization, and two, the contemplative practice that focuses only on liberation. The discourse between Vasiṣṭha and Bhuśuṇḍa in this narrative is the epitome of embodied and disembodied approaches to self-realization. The last part in this section weaves the narratives of Vidyādhara, Maṅki a sage, Pāṣāṇa or a Rock, Vispaścit, Śava a Corpse, and Tāpasa. The highlights of this section are two small sections identified as Vasiṣṭha Gītā and Brahma Gītā. In essence, this section focuses on the nature of liberation and a discourse on the absolute reality while describing the phenomena of the world through the perspective of the enlightened being. Concurrent are the themes of the illusion of time and space, of the nature of subjectivity, and of the reality of the world.

The yoga addressed in this text is not so much the physical āsana practice that has become the mainstream yoga of current popularity.

On the contrary, the text begins with depression and culminates in liberation.

Fundamentally, the Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha is addressing all the issues that became relevant after the development of the momentary stream-ofconsciousness theory as promulgated by the Yogācāra Buddhists, the non-dual nature of reality as the Brahman in relation to the illusory nature of reality as established by Śaṅkara in the school of Advaita Vedānta, and the absolute freedom of consciousness in constituting reality as propounded by the Trika philosophers of Kashmir. The yoga addressed in this text is not so much the physical āsana practice that has become the mainstream yoga of current popularity. On the contrary, the text begins with depression and culminates in liberation.

The problems addressed therefore are primarily psychological, and the issues related to the mind and mental phenomena are the central themes found throughout the text. Vasiṣṭha repeatedly addresses Rāma, chiding him for his limited ability to constitute his subjective mental state, and seeing the world through this altered state of consciousness. Noteworthy also are the concepts of relativism, the holographic nature of consciousness, parallel reality, different layers of time and space, altered states of consciousness, and embodiment and the world. The narratives of Līlā and Cuḍālā also raise the issues of gender and subjectivity. Accounts such as that of Lavaṇa also bring to the fore the issue of the caste identity. While the primary concern of the text is not the social fabrication of reality, this text can be used as a sourcebook for these issues.

Contemporary scholars such as Bhikhan Lal Arteya, Walter Slaje, Wendy Doniger, Christopher Chapple, Bruno Lo Turco, Jürgen Hanneder, and Sthaneshwar Timalsina have extensively studied these texts. Although there have been some summary and translation of the text, the complete version of Mokṣopāya has not yet been published. A philologically sound version of the Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha does not yet exist, and any inter-textual analysis of YV in relation to other classical texts and traditions is very rare. The nature of consciousness and reality as proposed in this text presents a holographic nature of reality, places consciousness as capable of constituting reality, and makes the questions regarding subjective states insignificant in light of the altered states of consciousness. The text deserves a clear phenomenological and cognitive psychological interpretation in order for it to be widely accessible to global scholarship. As for myself, I have found this text highly inspirational, and it has helped me in advancing my own meditation practice.