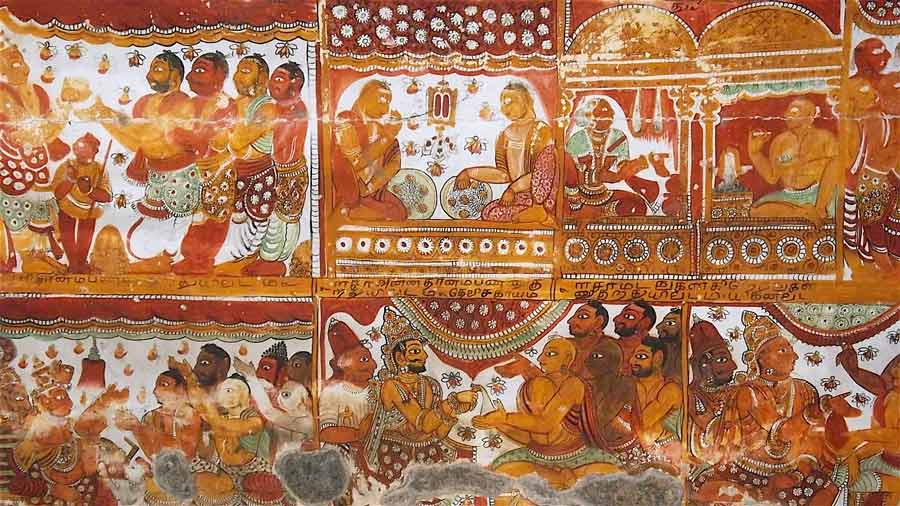

Nataraja Temple column, Tamil Nadu

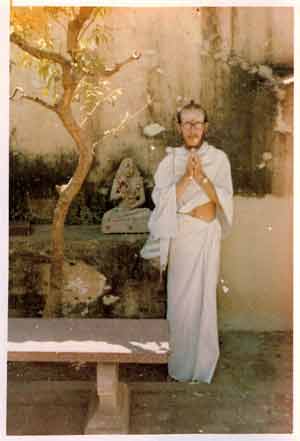

Marshall Govindan

(or Yogacharya M. Govindan Satchidananda) is a Kriya Yogi, author, scholar, and publisher of literary works related to classical Yoga and Tantra and teacher

of Kriya Yoga. He is the President of Babaji's Kriya Yoga and Publications, Inc., and the President of Babaji's Kriya Yoga Order of Acharyas, a lay order of more than 25 Kriya Yoga teachers operating in more than 20 countries.

Since the year 2000, he has sponsored and directed a team of six scholars in the Yoga Siddha Research Project in Tamil Nadu, whose

objectives include the preservation, transcription, translation, writing of commentaries and publication of the literary works of the 18 Tamil Yoga

Siddhas, from ancient palm leaf manuscripts. Until now, these important works of Yoga, Tantra, monistic theism, and Siddha philosophy have been unknown to

the English-speaking world. The latest of seven publications that have been produced from this project is the first English translation with commentary of

the Tirumandiram, the mystical classic by Tamil Saint Tirumular, which is one of the world's most important sacred texts related to Yoga.

Vikram Zutshi:

Tell us about your life before you found Kriya yoga. Describe the events leading up to your association with the practice.

M. Govindan Satchidananda:

I lived in Westchester, Los Angeles until I was eighteen years old. My father was an aerospace engineer and my mother was a homemaker for myself and my

younger sister and brother. We were all active in the local Lutheran Church. I played Little League baseball and was an Eagle Scout. I often went camping

in the Sierra Mountains with my parents or the scouts. I had my first balsawood surfboard in 1958 when I was ten years old, and during my high school years

I visited many beaches south of Los Angeles with a surfing club. I became very interested in foreign affairs from the time John F. Kennedy was in office.

This interest blossomed into a decision to seek a career in the U.S. Foreign Service after I made a cross-country trip to Washington, D.C. at the age of

sixteen. There I visited the school of Foreign Service, at Georgetown University, and later applied for admission and was accepted. Four years later I

graduated from their programme and passed the written and oral examinations for entry into the U.S. Foreign Service.

These were the events which highlighted my exterior life. But there were many things which happened during these formative years which had much more

significance in preparing me for the decision to become a celibate yogi and embrace a monastic way of life during the subsequent eighteen years.

At the age of fifteen, I had my first mystical experience during a weekend retreat with three dozen classmates. After everyone had shared in guided discussions

for two full days when no one had anything more to say, I suddenly went into a trance in which I saw that there was only One Being in the room,

speaking through, in and everyone there. I became aware of a reality which transcended all names and forms. Everything emerged from it. Everything

disappeared into it. During the months which followed, I sought ways to relive this wonderful vision. I began practicing meditation with the help of books

written by Alan Watts. I seriously considered joining a Zen monastery in Japan. I finally decided to first learn all that I could about the spiritual

traditions from the West and other cultures.

During my first year and a half at Georgetown University, I concentrated on my studies. Many of my professors were Jesuits. During the second year, I

participated in the class "Exploration into Spirit," by Father Thomas O. King, S.J. and attended some weekend retreats with him. He was the first mystic I

ever got to know. He was also the proctor on my dormitory hallway. Most residents stayed clear of him because he was known to have conducted an exorcism

over a period of several weeks in the Georgetown University Hospital psychiatric ward. He shared with us how much he enjoyed retreats with Tibetan monks.

We studied the works of Teilhard de Chardin, whose works had recently been released after Vatican II. Beginning in the summer of 1967, debates with

visiting politicians and anti-war demonstrations on campus began to erode my trust in the government.

My roommate's best friend was arrested and sentenced to twenty years for possession in a southern prison. He was the scion of one of America's most

distinguished families. In our attempts to help him, we came up against both the venality of the friend's family and the mafia's scheme to blackmail the

family. Disillusioned, I left for a junior year abroad programme at the University of Fribourg, in Switzerland, filled with existential questions.

Salvador Dali and Gala as I remember them, 1968

@Marshall Govindan

I arrived there nearly six months late, after the most important detour of my young life. While driving south of Carcassone, France, I picked up a hitchhiker,

young Englishman who invited me to spend some with him visiting his mother in Cadaques, Spain. He also mentioned casually that he would introduce me

to his long-time family friend there, Salvador Dali, the renowned surrealist artist. During the two weeks that I stayed in Cadaques, I visited Salvador

Dali and his wife Gala on several occasions. These visits had a profound and lasting effect on me. Through their eyes, I began to see the world in a new,

mystical light. Dali was an artistic magician. He was painting his first psychedelic artwork. He later named it "Hallucinogenic Toreador." While there, I

became friends with Philip Wellman, an electronic artist, whom Dali had engaged to construct an invisible cage for flies using sound waves. Philip and I

spent the next four months together, traveling down to Marrakech, Morocco, and back to Paris where we designed and installed the first light machines in

discotheques and enjoyed the company of many starlets and models in the exploding political and cultural revolution of Paris in 1968.

It all came to an abrupt end, when I received a letter from Georgetown University, informing me that if I did not begin my classes in Fribourg immediately,

I would be expelled. Expulsion would leave me highly exposed to the military draft. The previous four months had been so intense, that I never had a moment

to reflect; they seemed like four lifetimes. Given the choice between a year of peace and quiet reflection, or becoming a Vietnam war draft dodger chasing

hedonistic pleasures in Paris, I chose to return to academia in Switzerland.

To let go of all that had happened, beginning with the disturbing memories of the affair in the southern prison, Dali, Morocco and Paris, with its abrupt

ending, I began writing a novel, based upon all that I had experienced. It helped me to get it out of my system. A Benedictine monk, Père Utz, taught a

course on social ethics. As all of my courses were in French, there was a relief from the growing feelings of alienation from American culture. During that

year in Switzerland, I also met for the first time, a young, bearded, Indian monk. I was intrigued when he revealed that he maintained telepathic

communication with his Guru in India.

After the academic year ended, on the evening before my departure for America, I had one last dinner with my business partner, Philip Wellman, and our

sponsor, Monique de Balein at the Café Flore, in Paris. I told them that "during the months I had spent with them in Paris that I had fulfilled every

desire that I had ever had, and that I had nothing to further to look forward to doing."

A week after returning to America, in June 1969, sitting in my parents back yard in Los Angeles, as I was finishing my novel, my sister's boyfriend, John

Probe, dropped by and shared with me his experience in visiting the Self-Realization Fellowship's Lake Shrine in nearby Malibu. A couple of days later I

went there with him and purchased a copy of the Paramhansa Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi. In it, I found answers to my many existential

questions. So impressed was I with it, that after I finished reading it, I applied to join their monastery. I received a letter in return informing me that

before entering I must wait one year and practice the preliminary exercises.

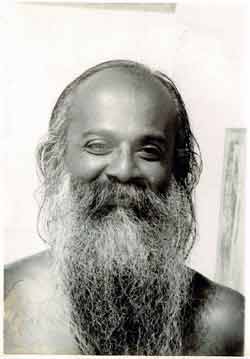

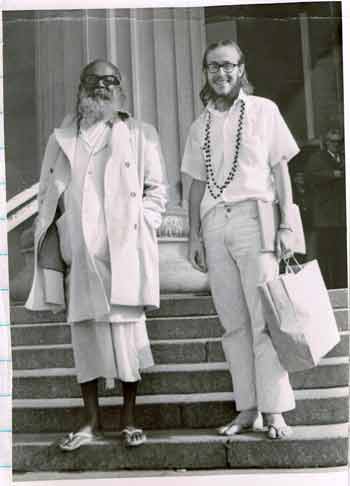

Yogi S.A. A. Ramaiah

@Marshall Govindan

I returned to Georgetown to complete my final year of studies there. In December of 1969, I noticed in a free newspaper a two line notice for "Kriya Yoga

classes. Out of curiosity, imagining that it must be a group of local students of the Self-Realization Fellowship, I attended my first class with students of

Yogi S.A. A. Ramaiah. A few weeks later he was there, in the tiny apartment where these weekly classes were being held. He was sitting on a bench, wearing

only a thin cotton dhoti from his waist to his ankles. I was immediately struck by the luminosity and peace emanating from him. His skin was the colour of

dark mahogany, and his long, full black beard had only a few streaks of gray. His voice was both sweet and powerful. In this first class with him, attended

by a half dozen of his students, he taught us the eighteen postures of Kriya Hatha Yoga, a meditation on "Being Still," lead us in some call and response

chanting, including "Om Kriya Babaji Nama Aum," and then gave a lecture for an hour and a half which had as its theme a verse from one of the poems of the

18 Tamil Yoga Siddhas, and ended with a period of questions and answers. I was deeply moved by the entire experience.

I attended all of the weekly classes at the center including one he lead every month until I attended a two-day initiation into Babaji's Kriya with him the

first weekend of June 1970, at his center at 112 East 7th Street, in the east village of New York City. During the months leading up to this, I

learned a great deal about Yogi Ramaiah's background from the leader of the D.C. center. I was inspired by his message; practice yoga intensively, work in

the world without being attached to it, and serve others. I decided that it would better to follow a living disciple of the great Himalayan master, and in

particular, one who manifested so much love for Him. Yogi Ramaiah exemplified this ideal, as a householder yogi and physical therapist.

I also sought and obtained the advice of Father King, who assured me that Kriya Yoga and Yogananda's teachings were divine.

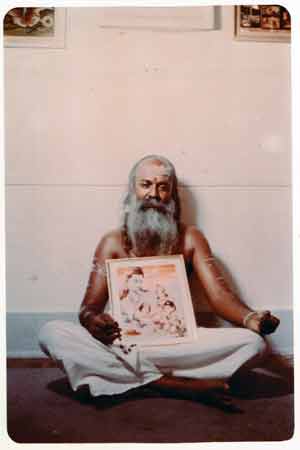

Yogi S.A. A. Ramaiah

@Marshall Govindan

After passing the Foreign Service entrance examinations, and after trying in vain to get Yogi Ramaiah to indicate to me what I should do with my life, I

finally decided to take the plunge, and not only receive initiation into Kriya Yoga but also to join the new ashram he was forming in southern California.

While a part of me felt alienated from modern, materialistic, war-mongering American society, another part wanted to somehow integrate my yogic spiritual

ideals with life in the world. I was also attracted by the disciplined way of life required of the residents of Yogi Ramaiah's ashrams. It involved eight

hours of practice of Kriya Yoga, eight hours of gainful employment, and eight hours of rest, personal maintenance and service each day. I

felt that this was just what I needed to avert me from becoming dispersed in too many directions. It also involved living an extremely simple, Indian lifestyle,

including diet and dress, which would be seamless between postings at ashrams he had established in North America, India or Sri Lanka.

I filed an application to the U.S. Selective Service Commission, my local draft board, for an exemption from military service, as a student of Divinity.

Yogi Ramaiah, my university roommate, and my father also wrote letters of support. To my surprise, the local board in Gardenia, California, a working-class

community of southwest Los Angeles granted to me an exemption, even though I was not proposing to study at any recognized theological seminary! I was

probably the first and only person in the history of the United States to receive an exemption from military service on the basis of studying Yoga as a

divinity student in a yoga ashram. I still find it amusing that today, yoga studio owners in America scoff at characterizing Yoga as religious.

In conclusion, I believe that the counter-cultural context of that period combined with the above mentioned personal events and conditions were the

essential motivational factors which enabled me to commit myself for the next 18 years to an intensely ascetic, Indian Yogic way of life under the

direction of a traditional Guru.

Babaji’s Kriya Yoga Ashram gate with the 18 Siddhas, Kanadukathan Tamil Nadu @Marshall Govindan

Vikram Zutshi:

What is Kriya Yoga and where does it come from? Describe your lineage.

M. Govindan Satchidananda:

Kriya Yoga is “Action with Awareness.” It is a means of self-knowledge, of knowing the truth of our being. Patanjali says that Kriya Yoga is intense practice (tapas),

svadhyaya (Self-study), and ishvara-pranidhana (surrender to the Lord) in the Yoga-Sutras, II.1.

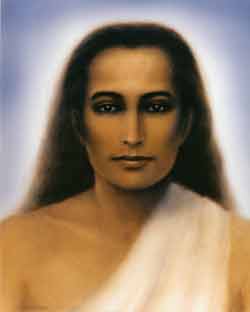

Babaji @Marshall Govindan

This tradition flows directly from the Yoga Siddhas, the perfected masters of Siva Yoga. Kriya Babaji Nagaraj synthesized his

Kriya Yoga from techniques of Kundalini Yoga taught by the Siddhas, Agastyar, and Boganathar, and revived its practice in modern times. He initiated Lahiri

Mahasaya into Kriya Yoga in 1862. Lahiri Mahasaya initiated the guru of Paramahansa Yogananda, Sri Yukteswar. Yogananda brought it to America beginning in

1920. His organization, the Self-Realization Fellowship continues the work of that lineage. Babaji also initiated V.T. Neelakantan, and my teacher, a great

yogi, S.A.A. Ramaiah into these techniques in 1954 and 1955, near Badrinath in the Himalayas. Yogi Ramaiah described it as "the scientific art of perfect

God-Truth Union," and "the practical side of all religions."

Babaji's Kriya Yoga is a scientific art of perfect God Truth union and Self-Realization. It was revived by a great Master of India, Babaji Nagaraj, as a

synthesis of ancient teachings of the 18 Siddha tradition. It includes a series of techniques or "Kriyas" grouped into five phases or branches:

Yogi Ramaiah and myself 1972 @Marshall Govindan

Kriya Hatha Yoga:

including "asanas," physical postures of relaxation, "bandahs," muscular locks, and "mudras," psycho-physical gestures, all of which bring about greater

health, peace and the awakening of the principal energy channels, “the nadis”, and centers, the "chakras." Babaji has selected a particularly effective

series of 18 postures, which are taught in stages and in pairs. One cares for the physical body not for its own sake but as a vehicle or temple of the

Divine.

Kriya Kundalini Pranayama:

is a powerful breathing technique to awaken one’s potential power and consciousness and to circulate it through the seven principal chakras between the

base of the spine and the crown of the head. It awakens the latent faculties associated with the seven chakras and makes one a dynamo on all five planes of

existence.

Kriya Dhyana Yoga:

is a progressive series of meditation techniques to learn the scientific art of mastering the mind - to cleanse the subconscious, to develop concentration,

mental clarity and vision, to awaken the intellectual, intuitive and creative faculties, and to bring about the breathless state of communion with God,

"Samadhi" and Self-Realization.

Kriya Mantra Yoga:

the silent mental repetition of subtle sounds to awaken the intuition, the intellect and the chakras; the mantra becomes a substitute for the "I" -

centered mental chatter and facilitates the accumulation of great amounts of energy. The mantra also cleanses habitual subconscious tendencies.

Kriya Bhakti Yoga:

the cultivation of the soul’s aspiration for the Divine. It includes devotional activities and service to awaken unconditional love and spiritual bliss; it

includes chanting and singing, ceremonies, pilgrimages, and worship. Gradually, all of one's activities become soaked with sweetness, as the "Beloved" is

perceived in all.

Through the practice of Babaji's Kriya Yoga ,

one begins to study oneself and to let go of negative habits,

desires, fears and other forms of disturbances.

One gradually establishes oneself in a new inner Witness perspective, full of peace and joy. As one lets go of the old egoistic perspective, one’s

personality is transformed, and one begins to experience oneself as an instrument of love and as a superior creative intelligence, engaged in bringing joy

to others and making the world a better place.

Babaji's Kriya Yoga is a spiritual tradition, wherein one “wakes up” from “dreaming with one’s eyes open.” Babaji's Kriya Yoga is a path of

Self-realization which is comprehensive, as it integrates all of the dimensions of our life. It is a path of self-discipline which enables one to live in

the world with open-hearted compassion.

Philosophically, it is monistic theism, and it reflects the teachings of the Tamil Yoga Siddhas, known as Siddhantha, which is very similar to Kashmir

Saivism.

Siddha Agastya @Marshall Govindan

Vikram Zutshi:

A recent book '21st Century Yoga' edited by Carol Horton does not feature any South Asians, only white people pontificating on their ideas about Yoga. One

would think Indian views on yoga do not belong in the 21st century. Thoughts?

M. Govindan Satchidananda:

Certainly Yoga has become a familiar term all around the world, particularly during the past 20 years, thanks to its adaptation to the

physical and cultural needs of Westerners and its commercialisation. The authors must ignore the fact that Yoga was brought to the West as a spiritual

discipline by teachers from India, beginning with Vivekananda, the monks of the Vedanta Society, Paramhansa Yogananda at the beginning of the 20th Century, none of whom taught Hatha yoga. In the 1960's and 1970's, it was said that there were more Indian yogis in New York City than in the

Himalayas! I knew many of them personally. In 1970, I represented my teacher at a meeting of several of them in Los Angeles with the intention to organize

a Kumba Mehla in Oregon, that would involve bringing hundreds of sadhus from India. Most of these teachers from India and Tibet started organizations or

ashrams which continue to function to this day. They range in size from that of the Art of Living, the Transcendental Meditation of the Maharishi, Ammachi,

3H0 Kundalini Yoga centers, SRF and the Vedanta Society, to much smaller ones including Sivananda Yoga, Integral Yoga, the Tibetan Shamballa centers, and

the Siddha Yoga Dham. They do not get as much attention in the media, but they continue to have a tremendous influence on the lives of a large proportion

of the second largest religious affiliation in America today, the "nones."

Yoga in the West has been adapted to the needs of our Western values, or culture, with its emphasis on materialism, individualism, looking good, keeping

fit physically, competition in school, work, business, and sports, commercialisation of everything, stardom, cultural chauvinism, and its widespread

ignorance of theology, religion, philosophy and other cultures. The word culture is derived from the latin word, culte, which means to worship. Five hundred years ago the West was a spiritual culture, as evidenced by the thousands of monasteries in Europe, now nearly all empty.

Today, the temples of our materialistic culture are the shopping malls. Yoga has adapted to the needs of helping Westerners to manage the effects of

stress, our greatest source of disease in the West, the effects of our needs to overarching needs to consume and compete.

Yoga has been treated in the West in the same manner that a remote tribe of Amazon Indians would treat a Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet airliner which had landed and

been abandoned in the Amazon jungle. The Amazonian Indians would treat it as a possible place of habitation, superior to huts. They would never even

suspect what was the purpose of this advanced technological device developed by the Yoga Siddhas.

The term "Yoga," in the view of those who cherish it traditional origins and teachings from India, has been hijacked by a wide assortment of entrepreneurs

who have sought to exploit it for commercial purposes. The purpose of Yoga is to become enlightened, a state of permanent freedom from suffering and

transcendence of egoistic consciousness. This purpose is rarely, if ever, even mentioned by Yoga teachers. In order to attract the greatest number of

participants to their classes, they must avoid any references to the terms and values which may put off those who are either Christian or atheistic. Most

of the Yoga teachers themselves in the West have little knowledge of Yoga's purpose because they have received so little training in its traditional

teachings. Sadly, Western practitioners of "yoga," are being taught something which is very far from Yoga's traditional sources and purpose.

Yoga has become more popular in India today than in the past several hundred years before it was invaded by the Mughals in the 15th century and

the British in the 18th century. When I lived in my teacher's Yoga ashrams in Tamil Nadu in 1972, and until the late 1990's, after initiating

young men into Kriya Yoga, their families would nearly always forbid them to continue to practice it, so great was the fear that they would renounce the

world and their families, and become monks. Classical Yoga, that which was associated with spiritual development, was widely considered to be limited to

Himalayan yogis and vows of renunciation. In my case, I was obliged to make numerous vows to ensure my commitment to my gurus. Even the present Prime

Minister of India, Narendra Modi, received his training during a two-year period as a young monk.

Yoga has become popular in India today for several reasons. The government of India has promoted it in schools throughout India, especially during the past

twenty years. This is a result of the many scientific studies funded by the central government of Yoga's benefits in the prevention and cure of many

diseases. The government has sought to avoid the excessive expense of allopathic (Western) approach to medicine, by promoting indigenous systems including

Ayurvedic, Siddha, and Unani.

As far as influence, most of the so-called "New Age" "personal growth" teachings and workshops are based on traditional Yoga, although few Westerners are

honest or even knowledgeable enough to attribute what they are teaching to Yoga.

Siddha Tirumular @Marshall Govindan

Vikram Zutshi:

How do the findings of modern science complement the wisdom contained in classical yoga texts?

M. Govindan Satchidananda: Neurological research confirms that samadhi is a measurable reality.Physiological studies, particularly those measuring brain function using electroencephalography (EEG) and positron emission tomography (PET), support Swami

Rama’s the assertion that “all of the body is in the mind, but all of the mind is not in the body.”[1] They

also demonstrate that various levels of neurological activity are correlated with different levels of consciousness, including those associated with

samadhi and enlightenment.

Delta waves with a frequency of less than 4 Hertz are most consistent with deep non-rapid (REM) eye movement sleep. (Hertz is a unit used to

measure the frequency of electromagnetic waves.) Theta waves between 4 and 8 Hertz are associated with concentration and meditation, dreams, hypnosis, and

hypnogogic imagery. Alpha waves with a frequency between 8 and 13 Hertz indicate deep physical relaxation, and beta waves between 13 and 30 Hertz suggest

alert functioning of the waking state. Gamma waves between 30 and 80 Hertz indicate the processing of multiple-sensory modalities and the execution of

specific cognitive or motor functions. For more information about meditation studies that used EEG, see the review by Cahn and Polich. [2]

A state of consciousness exemplified by creativity, invention, decision-making, problem solving, and the composition of lectures and research papers,

poetry, minutely detailed action plans, and the like is characterized by theta waves that verge on delta waves during deeper practice. The first stage of

samadhi is characterized by theta waves, followed by delta waves. During EEG monitoring, study participants experienced deep, non-REM sleep but remained

aware of their surroundings.

When samadhi deepens, one becomes aware of Kundalini, the subtle power of consciousness, leading to the alternation of theta and delta waves. When this

state is mastered and one can enter it at will, one progresses to turya, the fourth state of consciousness mentioned in yogic literature, such as

the Tirumandiram. When a Yogi maintains turya as a constant state of awareness, it is known in Yoga as asamprajnata (un-distinguished

cognitive absorption) or in Vedanta as nirvikalpa (no thought). It might be recognized by the absence of discernible electrical activity, although

this has yet to be demonstrated under controlled conditions.

What is reality? Recent scientific discoveries make one thing certain about the age-old question. It is certain that science does not have a good grasp of

reality. Two of the best models of physical reality, the theories of relativity and quantum mechanics, appear to be fundamentally incompatible.

Quantum mechanics describes the behavior of a system known as local realism. Local realism is fairly easy to understand: The properties of

particles can be described completely, and the properties remain localized, meaning that they can’t be transmitted to a different location faster than the

speed of light. It can be expressed more simply as: Things are the way they are, right here.

However, if you include a process known as entanglement, in which particles behave immediately under the influence of other entangled particles –

which may be half a universe away – you have a problem. The local reality is neither local nor … well … real.

In non-technical language, the more precisely one property is measured, the less precisely the other can be known or controlled. Werner Heisenberg argued

in 1927 that every measurement destroys part of our knowledge of the system that was obtained by previous measurements. In other words, the experiment is

affected by the observer.

In recent decades, quantum theorists have described entanglement. Two entangled subatomic particles, which can include photons moving at the speed of

light, have properties that are linked. Measuring the properties of one entangled item will cause the other to switch instantly from an indeterminate state

to a state in which properties are defined by its entanglement with the other. Because the entangled items can be far apart when this occurs, the transfer

of properties appears to occur faster than the speed of light. The results demand that we discard the idea of local reality.

Tirumular asks the same question as the theoretical physicists: How should we describe the Ultimate Reality? Is it the highest one? Is it Sadasiva

(the Lord)? Is it without form, or does it have properties? He agrees with the theoretical physicists: It is indescribable.

In the next verse, Tirumular drives the point home with an analogy, warning us:

Oh, fools, who see things with physical eyes,

Real bliss consists in seeing through the inner eye;

How can the mother express to her daughter

Her enjoyment with her husband?

—Tirumular (Tirumandiram, Verse 2944)

Just as the pleasure of love cannot be described, it is impossible to explain the bliss of experiencing Reality. We should be immersed in it, or we should

encounter something beyond our imagination.

Just as the salt in water, the Lord is immersed.

As parapara in para without any distinction;

The hidden implication is merged in the (word);

How? How? It is just like that.

—Tirumular (Tirumandiram, Verse 2945)

Para

refers to our highest or supreme Self – our soul – as distinct from the body, mind, or personality. Parapara refers to the Supreme Being. Both

share one essential quality: consciousness. But consciousness is neither an object nor an epiphenomenon (a by-product of brain activity) that depends

on the existence of a brain, as some materialists have argued. All living creatures, even those without brains exhibit consciousness. Consciousness is the

Subject, that which witnesses, that which observes. It pervades everything, both great and small, and so, it defies all attempts by physicists to measure

it. It is not an “it.” It is not “out there.” It is everywhere, within and without.

By raising the question “How? How?” Tirumular is referring to the inexpressible and translinguistic nature of the merging of the soul or individualized

consciousness with the Lord, or Supreme Consciousness. The answer cannot be defined in words or symbols but by turning within.

The key to realizing the truth, the underlying reality behind this world of ever-changing phenomena, lies in purifying ourselves of desire. As the Buddha

said: “Desire is a trap.”

Patanjali tells us:

[When there is] an ulterior motive, the resultant experience is [that there is] no distinction [between]

the awareness of manifest being in nature and the Self;

[when one practices] communion for its own sake, [one obtains] self-knowledge.

—Patanjali (The Yoga Sutras, III.35)

In other words, when desire (an ulterior motive) exists for anything except realization of Truth, one confuses the subject, our pure Self, with what we

experience in nature. In other words, we confuse that which is conscious – that which is the Witness – with any and all objects of experience as they

present themselves through our five senses, emotions, and thoughts.

Vikram Zutshi:

Describe The Thirumandiram and your work preserving and translating the text.

M. Govindan Satchidananda:

The Tirumandiram

, by Siddha Tirumular is a sacred, monumental work of philosophical and spiritual wisdom rendered in verse form. Encyclopedic in its vast scope, and written

nearly 2,000 years ago. it is one of India’s greatest texts, a spiritual treasure-trove, a Sastra containing astonishing insight. It is a seminal work and

is the first treatise in Tamil that deals with different aspects of Yoga, Tantra, and Saiva Siddhantha. My colleague, and co-sponsor of our Tamil Yoga

Siddha Research Project, the late, Dr. Georg Feuerstein, wrote a Yoga Journal review of our first publication of it, in 1995, saying that theThirumandiram is as important a yoga scripture as the Bhagavad Gita, the Yoga Sutras or the voluminous and inspiring Yoga Vaisihtha.

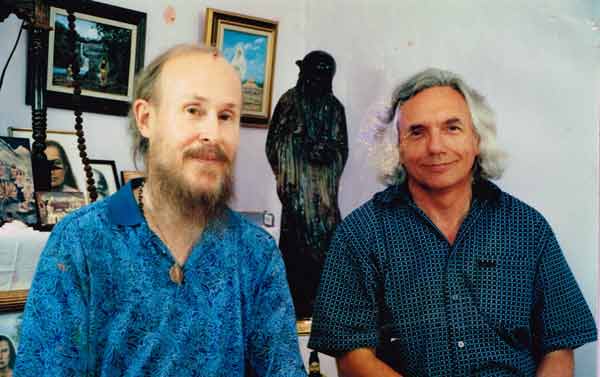

Marshall Govindan and Dr. Georg Feuerstein, co-sponsors of the Tamil Yoga Siddha Research Project, 2001,

Quebec @Marshall Govindan

It is a work which deals with how one may live a divine life in the midst of the worldly one. It fulfills the meaning of the word tantra, a web, which

joins the spiritual and the material dimensions of life. It expresses the thread of unity, which exists behind the many differences of time, country,

language, caste, religion, higher and lower, happiness and misery, wealth and poverty. It deals with all the aspects of life, which makes life worth living

by dealing with dharma, artha (prosperity), kama (sensual love), moksa (freedom from suffering), tapas (intensive

practice), yoga Jnana (wisdom), siddhi (perfection), buddhi (the intellect), the art of breathing, mantra, tantra, yantra, chakras, meditation, medicine, etc. In short, it is a Tamil encyclopedia of philosophical and spiritual wisdom rendered into

verse form.

In 2010 we published a new edition, which for the first time contained a verse by verse commentary, in addition to a much more accurate translation. It

required five years and a team of multidisciplinary scholars to translate each of its more than 3,000 verses and to write extensive commentaries about

them. This classic text contains five volumes and includes 3,770 pages in total.

The poems of Tirumular abound in technical terms conveying the mystical experience. The symbolic, twilight language of the Siddhas has the advantage of

precision, concentration, secrecy, mystery, and esoteric significance in that the symbols, at the hands of the Siddhas, become a form of artistic

expression of the inexpressible.

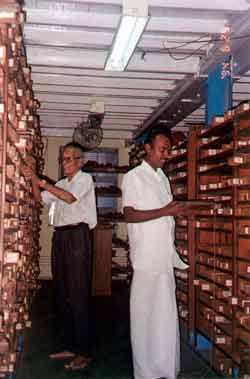

Dr. T.N. Ganapathy, Director and

Dr. KR Arumugam, Tamil Yoga Siddha Research

Project, Oriental Manuscript Library,

Chennai, 2002. @Marshall Govindan

The Yoga Siddha Research Project has been sponsored jointly by Babaji's Kriya Yoga Order of Acharyas Inc., Canada and Yoga Research and Education Centre,

Inc. California, USA since the year 2000. The aim of the project is to undertake on a grand scale to locate all the unpublished texts by the Tamil Yoga

Siddhas and publish them with critical annotations. Until now no serious study has been made of the Tamil Siddhas in a systematic and comprehensive manner.

No serious attempt had been made prior to this to translate or to write commentaries on the literary works of the Tamil Yoga Siddhas. This project has

filled this long-felt gap. The purpose of this project is to identify and preserve in computer-accessible format all of the palm leaf manuscripts of the

Tamil Siddhas related to Yoga from various libraries and private collections. The results have been published in eleven publications. Last February, after

fifteen years of effort, we published The Treasure Trove of Tamil Yoga Siddha Manuscripts, which contains several hundred critically edited

manuscripts in Tamil on a CD accompanied by a guide book. We are now collaborating with the Tamil University in Tanjore, Tamil Nadu, India, to continue

this work.

Vikram Zutshi:

What are the earliest references to yoga? Where did it originate and what are the different types?

M. Govindan Satchidananda:

Yoga has always been an oral tradition. My teacher would not allow us to write down what he taught. We had to memorize the practices. This is

characteristic of esoteric traditions. If you cannot record something in writing, the only way you can remember it is by practicing it regularly.

Consequently, the only persons who are capable of transmitting it to others are those who have practiced it extensively. This is how esoteric traditions

have survived for centuries, in small numbers of dedicated practitioners. This is the opposite of today's "new age" teachers, where everything is written

down, published, communicated, but few bother to practice. Even the teachers do not practice. The Yoga Siddhas never described in any details their Yogic

practices in their writings. They taught these only in person, to a few persons who had committed themselves to the practice. This is how Kriya Yoga

continues to be taught by teachers in all Kriya Yoga lineages.

There are references to Yoga in some of the Upanishads, which date to the few centuries b.c. The Tirumandiram and the Yoga Sutras are the first works which describe the practice of Yoga in a comprehensive and systematic manner. The Bhagavad Gita does too,

but with much less detail, and dates from this early period. The Gita refers to several types: bhakti (devotion), raja

(meditation), Jnana (wisdom) and karma (action). It also refers to Kriya. Kriya is derived from the word karma. Karma means action with

consequences; kriya means action with awareness. Not only do our actions have consequences, but so do our thoughts and words. So, Kriya is the antidote to

karma. Instead of reacting from samskaras (habits) or vasanas (tendencies), in practicing Kriya, one maintains the perspective

of the Witness, and responds consciously, after reflection.

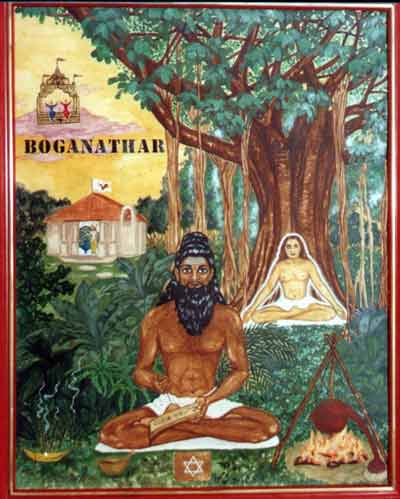

Siddha Boganathar @Marshall Govindan

Vikram Zutshi:

Describe the south Indian Siddha tradition and the legend of Bhoganathar. What does it have to do with your work?

M. Govindan Satchidananda:

Boganathar or Bogar, the Jnana Guru of Babaji, in the poem “Bogar Jnana Sagarama” (Bogar’s Oceanic Life Story, consisting of 557 verses, Verse number 2,

identifies himself as a Tamilian, and that the great Siddha Kalangi Nathar initiated him in Jnana Yoga (supreme self-knowledge). Kalangi Nathar was born in

Kasi (Benares), India. He attained the immortal state of soruba samadhi at the age of 315 and then made China the center of his teaching activities. He

belonged to the ancient tradition of Nava (nine) Nath sadhus (holy ascetics), who trace their tradition to Lord Shiva.

Boganathar practiced Kundalini Yoga in four stages. The first three stages are described my book Babaji and the Eighteen Siddha Kriya Yoga Tradition, in the chapter “The Psychophysiology of Kriya Kundalini Pranayama”. Boganathar chose the

Palani malai (mountain) in what is now southwestern Tamil Nadu as the site for intensive yogic practice (tapas) for the final stage of practice of Kriya

Kundalini Yoga and related practices.

He attained soruba samadhi at Palani, through the grace of Lord Muruga, or the eternal youth, “Kumaraswamy”. The Kumaraswamy temple at Palani became the

epicenter of his activities.

He visited many countries astrally, and physically and through transmigration. In one of his songs Boganathar claims to have flown to China at one point in

a sort of airplane which he built; he held discussions with Chinese Siddhas before returning to India. His visit to South America has been confirmed by

accounts left by the Muycas of Chile: “Bocha, who gave laws to Muycas, was a white, bearded man, wearing long robes, who regulated the calendar,

established festivals, and vanished in time like others (other remarkable teachers who had come across the Pacific according to numerous legends of Incas,

Aztecs and Mayans) in Rao's Hindu America, a fascinating book which documents the linguistic, archaeological, and anthropological evidence of

early visits to the Americas by travellers from India and China.

Boganthar writes about how his guru, Kalangi Nathar decided to enter into samadhi in seclusion for 3,000 years. He summoned Boganathar telepathically from

Tamil Nadu to China to take over his mission. Boganathar traveled by sea, following the trade route. In China, he was instructed by Kalangi Nathar in all

aspects of the Siddha sciences. These included the preparation and use of the kaya kalpa herbal formulae to promote longevity. After Kalangi Nathar entered

into trance, Boganathar assumed his teaching mission to the Chinese. To facilitate this, he transmigrated his vital body into the physical body of a

deceased Chinese man, and thereafter went by the name “Bo-Yang”. “Bo” is a derivation of the word “Bhogam” which means Bliss, material and spiritual.

Boganathar decided to overcome the limitations of the Chinese body with its degenerative tendencies and prolong its life through the use of the kaya

kalpa herbs long enough for the effect of Kriya Kundalini Pranayama and related yogic techniques to bring soruba samadhi. In his poem Bogar Jnana

Sutra - 8, verse number 4, he describes vividly what happened after carefully preparing a tablet using thirty-five different herbs:

With great care and patience I made the (kaya kalpa) tablet

and then swallowed it;

Not waiting for fools and skeptics who would not appreciate

its hidden meaning and importance.

Steadily I lived in the land of the Parangis (foreigners)

For twelve thousand years. my fellow!

I lived for a long time and fed on the vital ojas

(sublimated spiritual energy)

With the ojas vindhu I received the name, Bogar;

The body developed the golden color of the pill;

Now I am living in a world of gold.

This kaya kalpa enabled Boganathar to transform the Chinese body over a period of 12,000 years, during which time it developed a lustrous golden color.

(The physiological transformation to the state of soruba samadhi was, however, completed only later, at Palani in the final phases of Kriya

Kundalini Yoga and related practices.

In this poem Sutras of Wisdom — 8, he sings prophetically of the taking up of the practice of pranayama in modern times by millions of persons who would

otherwise have succumbed to drug abuse:

Will chant the unifying verse of the Vedanta,

Glory to the holy feet of Uma

(the Divine Mother of the Universe, Shakti),

Will instruct you in the knowledge of the sciences.

ranging from hypnotism to alchemy (kaya kalpa),

Without the need for pills or tablets,

the great scientific art of pranayama breathing,

will be taught and recognized

By millions of common people and chaste young women.

Bo-Yang became also known as Lao-Tzu, and was accessible for nearly 200 years, and trained hundreds of Chinese disciples in Tantric Yoga practices. At the

end of his mission to China, about 400 B.C., Boganathar, with his disciple Yu (whom he also gave the Indian name Pulipani) and other close disciples, left

China by the land route. As recorded in the Taoist literature, at the request of the gatekeeper at the Han Ku mountain pass Lao-Tzu crystallized his teachings. He did so, in two books, the Tao Ching, with 37 verses, and

the Te Ching with 42 verses). Taoist yoga traditions continue to seek physical immortality using techniques remarkably similar to those taught in Tamil Shiva Yoga Siddhanta.

The Yoga of Boganathar, volume 1

@Marshall Govindan

While Boganathar is reported to have left the physical plane at Palani, he continues to work on the astral plane, inspiring his disciples and devotees, and

even in rare instances, he transmigrates into another’s physical body for specific purposes. Several revered persons, including Yogi S.A.A. Ramaiah, Swami Satchidananda of Yogaville, Virginia and Coimbatore, India and Sri Dharmananda Madhava of Palani in India have related accounts to me of how they have seen him and been initiated by him in visionary experiences.

Yogi Ramaiah, in delivering lectures upon the verses of Siddha Boganathar, seemed to be so infused with the spirit and genius of the Siddha, and interpret them with so much inspiration, that it seemed as if Boganathar himself was speaking through him. After one of these memorable lectures, I told Yogi Ramaiah how much I enjoyed the lecture. He replied: "I enjoyed it too!"

A memorial samadhi shrine dedicated to him is situated in the Palani temple complex.

The Tamil Yoga Siddhas Research project had its origins around 1961 when Kriya Babaji Nagaraj gave to Yogi S.A.A. Ramaiah, the solemn task to gather the

palm leaf manuscripts of the 18 Tamil Yoga Siddhas, and to preserve, transcribe and publish them, beginning with those of Boganathar. During the 1960's

Yogi Ramaiah wandered all over Tamil Nadu collecting and carefully preserved them. In 1968 he published "Songs of the 18 Yoga Siddhas," a small anthology

of these in their original Tamil language. From 1979 to 1982 he published the collected works of Babaji's guru, the Siddhar Boganathar, in their original

Tamil, in three volumes, nearly 1,800 pages in length. I assisted him in this project while living in India for nearly four years. In 2003 and 2005, we

published The Yoga of Boganathar in two volumes, produced by our research project. It included English translations and commentaries of

many of these verses found in these manuscripts.

M. Govindan Satchidananda @Marshall Govindan

Vikram Zutshi:

Who are the 18 Mahasiddhas? What is their contribution to what we understand as Yoga and Tantra?

M. Govindan Satchidananda:

Shiva Puranas are filled with stories which describe how Lord Shiva, (the name of God among a major sect of Hinduism) has sat in meditation on Mt.

Kailas,Tibet since time immemorial. He is worshiped by the yogis as Lord, and by all the gods as the supreme Lord. The history of the Siddha tradition

begins ages ago with the story of Lord Shiva’s initiation of his consort or Shakti, Parvati Devi, into Kriya Kundalini Pranayama (the scientific

art of mastering the breath) in a huge cave at Amarnath in the Kashmir Himalayas. Later, the Shiva Puranas state that Yogi Shiva initiated others,

including the Siddha Agastya and the Siddhas Nandi Devar and Thirumoolar on Mount Kailas in Tibet. Agastya subsequently initiated Babaji in the year 203

a.d. According to the traditions of southern India, there are eighteen Siddhas in particular who attained perfection, which included their spiritual,

intellectual, mental, vital and physical bodies. The names of these eighteen Siddhas vary according to different sources. Our research concludes that they

most likely included the following: Tirumular, Rama Devar, Agastayar, Konkanavar, Kamalamuni, Satttamuni, Karuvoor, Sunderanandar,Valmiki, Nandi Devar,

Paambatti, Boganathar, Macchamuni (Matysendrenath), Patanjali, Dhanvantri, Gorkanath, Kudambai, and Idaikadar. Apart from these eighteen, popularly known as

the “Pattinettu” (Eighteen) Siddhas, there are a number of others who appear in other lists from various sources. They include Konkeyar, Punnakeesar,

Pulastiyar, Poonaikannar, Pulipanni, Kalangi, Aluganni, Agapaiyer, Theraiyar, Roma Rishi, and Avvai. The number eighteen may also refer to an infinite

number symbolically.

The Tamil Siddha’s metaphysical research was not divorced from their discoveries in the field of medicine. Some of them achieved mastery over nature,

through Yoga, and through medicine. In developing and experimenting with the yogic Kriyas (techniques) the Siddhas acquired much knowledge of human anatomy

and physiology, as well as in the fields of medicine and the processes of rejuvenation. The Siddha System of Medicine, or “Siddha Vaidya” as it is commonly

known, is today one of four systems of medicine recognized officially in India.

The Siddha’s, or “perfected ones” developed a system of medicine known as the Siddha system of medicine, which can be traced to the pre-Vedic period. The

word “siddha” is derived from its root, “siddhi” which generally refers to the perfection of the aims of yogic self-discipline, or to one of the eight

kinds of supernatural powers attainable by man. Using these powers, they undertook a systematic study of nature and its elements and from what they were

able to grasp they developed a highly systematized medicine. They left behind a large body of knowledge

recorded in palm-leaf manuscripts, which were passed down and transcribed from one generation to another of hereditary families of physicians.

Some will perhaps find it odd to learn that the Siddhas’ mastery over nature came as a result of two seemingly unrelated subjects: yoga and medicine.

Particularly in the west in modern times, where everything becomes a field of specialization, the integrating of the “spiritual” and the “scientific” may

appear to be impossible. The Siddhas were scientists, particularly in their investigations into chemistry, astronomy, plants, human anatomy and physiology.

They applied their extraordinary powers, developed through intensive yogic practices, to research these areas on atomic and universal levels without the

use of sophisticated equipment.

The aim of the Siddha system of life is that man must reconcile the antagonistic tendencies of his earthly individual nature and of his divine transcendent

essence by satisfying the antithetical claims of both spheres, the natural and the super-natural: the phenomenal realm of body and psyche, and the

imperishable essence which forms man’s inherent being.

The Siddha does not to disregard earthly well-being in his pursuit of beatitude. On the other hand, only insofar as he is able to bring about a union with

the transcendental essence inhabiting his own nature and the universe, will he be able to ensure for himself the health and well-being and so keep himself

immune to assaults from diseases and evil passions which threaten his life and well-being. This view is summarized by the definition of medicine given by

one of the greatest of the Siddhas, Thirumoolar:

Medicine is that which treats the disorders of the physical body;

Medicine is that which treats the disorders of the mind:

Medicine is that which prevents illness;

Medicine is that which enables immortality.

How advanced was the Siddhas’ conception of medicine when compared to that of “modern” medicine, which only in this century has included mental illness

within its scope of treatment, and has not yet begun to conceive of physical immortality.

Enlightenment : It's Not What You Think, the new book by Marshall Govindan Satchidananda is out now. For some sample pages and endorsements from Dr. Christopher Key Chapple, Dr. David Frawley, Pandit Rajmani Tigunait, Dr. Richard C. Miller and Dr. T.N. Ganapathy can be read, follow the link:

http://www.babajiskriyayoga.net/english/bookstore.htm#enlightenment_book