Hand with a gold thread

THE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE TEACHER

Traditionally the Sufi sheikh is the “keeper of the gates of grace.” Love and grace are the cornerstones of the relationship with the teacher,

which is the most important relationship for the disciple. Without this relationship there is no path and no journey. Through the grace of the

teacher the disciple is given the love and guidance that are needed for the journey. The disciple progresses through love, and if the disciple does not

herself possess enough love, the teacher will create love in her heart.

But the relationship with the teacher is probably the most paradoxical and confusing element of all on the Sufi path. It is the most intimate and yet the

most impersonal relationship we will ever have. It is most intimate because it happens within the heart and is a relationship of pure love. And yet this

relationship is completely impersonal because it belongs to the soul; it has nothing to do with our ego or personality, or with the person we perceive the

teacher to be. For the teacher, while still functioning as a human being, has through the grace of his teacher been made empty, has become “featureless and

formless”; in the Sufi tradition the teacher is said to be “without a face, without a name,” stressing the impersonal nature of the teacher.

Yet in the West we have been conditioned to understand love and nearness solely within the sphere of personal relationships; we have no concept of a

deeper, impersonal love that belongs to the soul. Our hunger for personal acceptance, our unmet emotional and even physical needs come to the surface and

are easily “spiritualized” and projected into the relationship with the teacher. We lack the traditional container that separates this relationship from

the personal sphere. In many Eastern traditions, for example, the disciple cannot address the teacher directly; he must first wait to be spoken to. In the

West we have no such protocols.

Furthermore in America relationships of all kinds are marked by a certain informality — even strangers address each other by their first names. So while no

one would have thought of addressing Bhai Sahib or Mrs. Tweedie (as she liked to be called) by their first names, it seemed appropriate for people in

America to address me as Llewellyn. And yet I gradually noticed the confusion this created and the desire it fed to personalize the relationship with the

teacher. This tendency is emphasized by the fact that the majority of people attracted to this path in the West are women, who tend to be naturally

relational and experience relationships much more than men do in the personal sphere. And this whole problem is further compounded for the Western seeker

by the absence in our culture of any tradition of the relationship with a spiritual teacher. In India the relationship with a guru has always been

a part of the culture, while in the Middle East the Sufi sheikh has been a recognized (if sometimes persecuted) figure of spiritual authority. But

in the West the relationship of master and disciple, although imaged in the life of Christ, has never been part of our spiritual landscape, and we have no

experience within our own culture to turn to for an understanding of its real nature or for guidance as to how to conduct ourselves within it.

The love that comes from the sheikh is pure and unconditional, uncontaminated by any of the patterns or problems that define our normal

understanding of relationships. This love does not belong to duality and the normal dynamics we associate with a relationship. It belongs to divine

oneness, and is present within the heart of the sheikh from the beginning. As Bhai Sahib described it to Irina Tweedie,

“Love cannot be more or less for the Teacher. For him the very beginning and the end are the same; it is a closed circle. His love for the disciple does

not go on increasing; for the disciple, of course, it is very different; he has to complete the whole circle…. As the disciple progresses, he feels the

Master nearer and nearer, as the time goes on. But the Master is not nearer; he was always near, only the disciple did not know it.” [17]

Stepping into the presence of the sheikh, the wayfarer enters this dimension of love’s oneness. Yet she does not know this; she has not yet

developed the faculty to recognize or to consciously appreciate what is being given. Instead she remains within the prison of her projections, mental

conditioning, and psychological problems, which of necessity become projected into the relationship with the teacher.

Love evokes both positive and negative psychological projections. And as anyone who has experienced a human love affair knows, the greater the love, the

more powerful the projections—the more the unlived parts of our psyche clamor for attention, want to be drawn into the sunlight of our loving. The

unconditional love that is given by the sheikh will of necessity evoke many projections, many of them unexpected and unwanted, along with many

unmet needs. Once the initial “honeymoon period” of intoxication has passed, this is what the disciple is forced to confront. And because the sheikh is also a figure of authority, the disciple’s unresolved authority issues will also surface, adding to the cloud of confusion that obscures

the real nature of the relationship with the teacher—the love that is the essence of the Sufi path.

For the sheikh this love is the prima materia of the path, both the beginning and the end of the work. Through love the disciple is swept

clean of impurities and remade, so that she can live her deepest nature, her inborn closeness to God. While the disciple confronts the obstacles her mind

and psyche place in the path, the sheikh does the real work of transformation, softening the heart and preparing the disciple for the awakening of

the consciousness of the heart, the divine consciousness that is present in the innermost chamber of the heart, what the Sufis call the “heart of hearts.”

Much of the work of the path is a process of preparation, an inner purification to enable the heart of the disciple to contain this consciousness without

contamination by the ego or lower nature, the nafs.

When the sheikh receives the hint that the disciple is ready, the consciousness of the heart is awakened in the disciple through the grace of thesheikh, through a transmission from the heart of the sheikh to the heart of the disciple. This infusion of divine love is the gift ofsirr: “a substance of God’s grace, produced by the bounty and mercy of God, not by the acquisition and action of man.” [18] The word “sirr” means secret; sirr is a secret substance, hidden

from the world because it does not belong to the world but belongs to the mystery of divine love. It is the essence of the relationship of lover and

Beloved: “He loves them and they love Him.”[19] Without it there can be no

realization. For the Sufi, sirr is the most precious substance in the universe.

Only the teacher can give us what we need, this most precious gift, and yet what is given cannot be grasped by our mind or ego. Through the grace of the sheikh the disciple eventually awakens to the consciousness of oneness that is the knowing of love. But for many years on the path this

consciousness is hidden from the disciple, who is faced with the limitations of the ego and the confusions of the psyche. The disciple cannot help but see

the teacher through the veils of duality and the distortions of her own projections; she cannot help but try to bring this relationship that belongs to the

impersonal level of the soul into the personal landscape of her ego-self. This is what makes this link of love so difficult to follow, this thread so

seemingly tenuous. But if we follow it with sincerity, devotion, perseverance, and a sense of humor, we will awaken to the real nature of this most

bewildering, most potent of relationships; we will come to know how the heart of the sheikh reflects the oneness of love’s hidden face.

Woman listening to the earth. image by Anat Vaughan-Lee

FEMININE QUALITIES ON THE PATH

Sufism is a path of love and longing that pulls us into the depths of the heart. Longing is a central note on the Sufi path; it is the feminine side of

love: the cup waiting to be filled. Longing draws the wayfarer inward to live the heart’s devotion. Maybe this is why so many who are drawn to the path in

the West are women: they are attracted to this mystery of longing, this path of devotion, in which they recognize an intimate part of their own nature. In

American culture especially the qualities of the feminine have been denied and repressed, often brutally. Although there is an appearance of sexual

equality in America, in this very masculine and extroverted culture there is little real appreciation of the feminine, her power and inner qualities; in

fact, in America the deeper aspects of the feminine have been almost completely removed from the collective landscape.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, despite this deep resonance of the feminine with the Sufi path, when I first began working in America I noticed in the

women who came to this path a deep-seated fear of allowing their longing, of opening to their heart’s intimacy. They were unsure about sharing dreams and

experiences that expressed the inner intimacy of the path and the heart’s love affair. A collective stamp of abuse and dismissal of the feminine had

created a wound that held them back. We responded to this by creating a women’s group where women could explore these issues without the inhibitions caused

by the presence of men. Gradually, after a few years, the women felt instinctively safe enough to be present, open, and vulnerable, and then there was no

longer any need for a women’s group.

An initial work of bringing this path to America had been completed: a container for women for the real work of the soul had been created. This was an

important step, as I became increasingly aware of how qualities that are natural to the feminine are essential to living the heart’s longing for God. For

the work of the path to take real root in this masculine culture, the feminine mysteries of love—the sanctity of longing, the receptivity of the heart, the

way of devotion—need to be reclaimed and honored.

Women have a natural affinity for this work. For women know the wisdom of receptivity, of holding a sacred space. They experience this in their bodies

through the wonder of pregnancy; but the sacred feminine also knows how this works within the soul: how the heart is always awake, waiting and longing for

her Beloved, for that moment when love comes secretly and sweetly; how within the heart love and longing create a space for the divine to be born. Then the

heart becomes “light upon light,” as Rumi describes it: “a beautiful Mary with Jesus in the womb,” [20] which in time can give birth to the divine as a living presence within

ourselves and in our lives.

Women also understand the importance of stillness, of simply being. For how can we be receptive when we are busy all the time? In the West we are addicted

to activity. We think that the problems of the world and of ourselves can only be solved by going out and doing something, not realizing that it is this

focus on ceaseless activity that has created much of our present predicament. When we are not busy solving our problems, we are caught up in an endless

round of distracting activity, busyness for its own sake. In response to everything we automatically ask, “What should I do?” But the feminine knows to

ask, “How should I be?,” understanding that from a state of still being we can listen, be attentive and aware. We can perceive what life, both within us

and around us, is showing us—“We shall show them Our signs upon the horizons and in themselves, until it is clear to them that He is the real.”[21]

Just as a mother instinctively knows how to listen to her children, so does the sacred feminine know how to listen inwardly and outwardly to life, to

experience and participate in this sacred mystery of which we are a part. This is the basis of a real relationship to life and to our soul; it is how we

can learn to live the life of the soul rather than the illusory life of the ego. Life is a direct expression of the divine, but unless we listen to this

hidden presence, we experience only the distortions of the nafs with all its desires and anxieties. Listening within, we hear what our Beloved is

telling us; we come to know the mysteries He whispers into our heart and soul. We also learn to distinguish between the voice of the ego and the voice of

the Self: to become attentive to the hint of the Beloved, and yet vigilant to the deceptions of the ego.

Life and the soul are always beckoning us, wanting to share the real wonder of being alive. When we really listen, our outer and inner life can speak to

us, and take us on a journey far beyond the limited world of the ego. We can begin to discover the divine mysteries of love within our hearts and in the

world around us. The mysteries of love are feminine in their nature, just as the nature of the soul is feminine as it looks towards God, always attentive

and receptive. We need to reclaim these feminine qualities that have been so devalued in American culture and recognize their essential value, and bring

them back into the our lives.

AUTHORITY AND POWER

Sufism is a path of love, but it is also has the aspect of power and spiritual authority. This presents another difficulty for Americans on the path.

America is democratic by nature; there is little collective understanding here—in fact there is a great deal of suspicion—of real spiritual authority or

power. In addition to that democratic conditioning, the centuries-long dominance of masculine hierarchies in the West and their abuse of power has made

many seekers understandably hesitant about power; particularly in women there is a deep fear and distrust of masculine authority, after centuries of abuse.

Yet deferring to the power and the inner authority of the teacher is an essential aspect of the way we are trained to bow down before God. For how can we

become His servant if we are not trained to do what we are told? If we are asked to do something and we hesitate, even for an instant, the moment can be

lost.

When I met Irina Tweedie, I immediately knew that I was in the presence of real spiritual power, just as when she first met her sheikh something

in her instinctively bowed down. I knew with a knowing that had no outer logic that I had to do whatever I was told. For many years I thought that she was

my teacher, until she explained that I belonged to her sheikh, Bhai Sahib, and that when I first came to the group she had been told by him in

meditation to leave me alone, that he would look after me. (This connection with a teacher who no longer has a physical presence is known as uwaysi, and is part of the Naqshbandi tradition.[22])

I was trained by my sheikh in the ancient way of trial and love, in which the disciple becomes “less than the dust at the feet of the sheikh.” For

example, there was a period of two years in my early twenties when he did not let me sleep for more than three hours a night, destroying my patterns of

resistance and spiritual arrogance through the simple—but very effective—means of exhaustion. Finally, one summer afternoon, in the most intense few hours

of my life, I was confronted by the deepest suffering of my whole being, until in a moment of revelation he awakened my consciousness on the level of the

soul. Then gradually, over the following years, I became aware of the depths of my belonging to him, and came to know that I am here to serve him, that I

have been trained to do his bidding. He guided me with kindness and severity. Once, when my children were young and I was continually tidying the house

after them, his voice gently came to me, “You don’t have to keep tidying up!” On another occasion, when I was suffering intensely from the awakening of my

kundalini energy,[23] Mrs. Tweedie asked Bhai Sahib if he could help me. His

response was simply, “He can bear it.”

My relationship with my sheikh is one of total subservience and love, based on a recognition that nothing matters in this world except to do his

work and to please him. I came to know him as an inner presence, someone I could turn to in meditation and prayer, whose help would be present when I

needed it most. And yet often over the years he seemed to leave me alone to struggle with my difficulties and to make mistakes. I have experienced the

devastation of emptiness and desolation when this connection was veiled, and anguish when I displeased him, when I felt that I failed my sheikh.

But I have come to know that this relationship is the one thread of love that this world cannot break, because it is made of a different substance that is

stronger than all the difficulties of this world. It belongs to the ancient secret of love and devotion, a belonging so primal that it exists before

creation. It is part of the substance of the soul and gives meaning to every moment of every day.

Held by this thread of love, this connection from heart to heart, I was given a love so complete that every cell of the body was fulfilled and I knew the

bliss of the soul. I was taken from the world of duality back to the oneness of the heart, and further, into the dimensions of non-being, the emptiness

that is the real home of the mystic. I was shown the infinite inner spaces where love is born, and a quality of consciousness that belongs to light upon light. In the ancient tradition, I was destroyed and remade, so that I could be of service to my sheikh and the Beloved. When

I first came to the path I was an arrogant nineteen-year-old who had had a few experiences in meditation and thought he knew something about spiritual

life. But unknowingly I was taken in hand by a great master who taught me humility and the simplicity of real service. He opened my heart and awoke me to a

realization of the oneness of life that is all around us. And he guided me, with humor, patience, and love, knowing my faults and accepting me.

Through this relationship I have also come to know the real power that belongs to God and those who are in service to God. In our outer life we often see

the power dynamics people engage in playing out around us, in the family or the workplace, or more corruptively on the world stage. But in the relationship

with a real teacher, one who is merged into the Absolute, who is one with God, there is a power of a completely different magnitude, a power that belongs

to the Creator and not the creation. This is a power that wants nothing for itself but just is. When I experience this power inwardly, in the

presence of my sheikh, my whole being trembles and bows down. When people talk about a spiritual teacher in terms of power dynamics, something in

me laughs, because it is clear they have no idea what real spiritual power is. The disciple does not argue or doubt before such pure energy. The only

response is awe.

Image by Anat Vaughan-Lee

THE WORK OF THE AWILIYA AND THE SOUL OF THE WORLD

Behind each teacher stands a succession of spiritual elders, each supported and guided by those who have gone before. To be responsible for the soul of a

wayfarer is one of the greatest responsibilities one can be asked to carry, and without the inner presence of my sheikh I could not guide anyone:

he watches over me and confronts me with any mistake I might make. This hidden dimension of the path is hardly known in the West, where only what is

visible is recognized, but it is an essential aspect of Sufism.

In the Naqshbandi path the succession of superiors is combined with the tradition of the Khwajagan (masters), a number of early Naqshbandi sheikhs whose spiritual power and authority were recognized even in the outer world, sometimes by worldly leaders and kings. The Naqshbandiyya

became known as “the path of the masters.”

The Khwajagan were visible in the Middle East from the eleventh to fifteenth century. They had access to inner spiritual powers, but another

secret of their success and influence was their consistent avoidance of any worldly position of wealth or power. Their influence was based on the love they

inspired in all who met them.[24]By the sixteenth century their outer

influence had become less visible, but the work and authority of this succession of Naqshbandi masters continued in the inner worlds, where it can be

linked with the Sufi tradition of the awiliya.

The awiliya are the Friends of God, a spiritual hierarchy consisting of a fixed number of evolved incarnated beings who watch over the world. At

the top of the hierarchy stands the pole (qutb), “the Master of the Friends of God,” who is the axis around whom the exterior and interior

universe turns. Under the pole come seven pegs, below which come the forty successors (al-abdâl).[25] If one of these Friends of God dies, another is waiting to take his place,

so that the number of Friends is always maintained.[26] Without the awiliya the existence and wellbeing of the world could not be sustained.

Over the last centuries the awiliya have been hidden; their spiritual work has gone on undisturbed. But the existence of a spiritual hierarchy

working to maintain the wellbeing of the whole world has remained part of spiritual consciousness in the East. In the West, however, we have identified the

spiritual path almost exclusively with the process of individual transformation and have little understanding of this larger, global dimension.

Sadly, in the West much of our understanding of spiritual life has been subverted by the values of the ego. Only too often we see spiritual life solely in

terms of self-development, the desire for progress, self-empowerment or the achievement of spiritual states. We completely miss the basic principle that

the path is never about us, about our individual or spiritual wellbeing. To be spiritually mature is to recognize that we work upon ourselves not for our

own benefit but for the sake of service: service to our Beloved and to the whole of life—in the oneness of His love there is no difference.

In order to fully claim the heritage of Sufism and the tradition of the awiliya, the masters of love, we need to step out of our confined vision

of the path and recognize that there are deeper levels of commitment and service than we have been aware of in our pursuit of our own private spiritual

goals. Traditionally His lovers and the friends of God look after the wellbeing of the world, “keeping watch on the world and for the world.” Spiritual

groups and individuals have always assisted in this work, working in the inner realms to bring love and light where they are needed. Through their prayers,

devotions, and other practices they work, sometimes knowingly but more often unknowingly, to make their light available. The wayfarer’s consciousness has

not traditionally been necessary to this work. Much spiritual work happens on the level of the soul where it is veiled from the everyday consciousness even

of those who are involved; it is difficult for the mind to comprehend levels of reality beyond its immediate perception, and often it is best for the ego

not to know what we are doing.

Now, though, at this time of global crisis which is also a time of global transformation, there is a need for spiritually aware individuals to participate

consciously in this global dimension of spiritual work. In the West we have identified spiritual work too limitedly with our individual inner journey or

outer acts of service. We need to know that we are a part of a network of mystics and masters of love who are helping the world come alive with love,

working from within to redeem a world that has become desecrated through our forgetfulness.

For the world is a living being, possessed of a consciousness and a soul. The soul of the world, the anima mundi, is the spiritual center of the

world, a spinning organism of light and love that exists at the world’s core. Without it, the world would be nothing more than shadowy images without

purpose or meaning. In the same way that the light of our own soul brings meaning to our lives, and that turning away from the needs of our soul brings

emptiness and despair, the soul of the world makes the world sacred, and our mistreatment of the world creates both an outer and an inner wasteland. Our

obsessive materialism and the greed it has spawned have covered the soul of the world in a cloud of forgetfulness, polluting our physical planet and

draining joy and sacred meaning from life.

At this moment of crisis and opportunity in the evolution of the world, it has become a part of the work of this Naqshbandi path to bring our awareness to

the work of reawakening the soul of the world, of purifying and redeeming it so that its light can once again flow into life and nourish all of creation.

What has been the work of the masters mainly on the inner planes, in which seekers have participated mostly unknowingly, is now becoming our conscious

focus as well. Wayfarers need to recognize and accept their role in this work: to turn their focus away from their own spiritual journey and dedicate their

spiritual life and experience to the benefit of the world. Through our spiritual practices we gain access to our divine light; through the teachings of the

path we learn to live it in our daily lives. Now through the inner work with the masters of love we have to learn consciously to use our light for the sake

of the world—to shine our own light where it is needed, and to work with the body of light that is the soul of the world.

The soul of the world is everywhere. Just as the soul of the individual is present throughout the body, the soul of the world permeates every cell of

creation. It is made up of the light of the souls of all of humanity and a substance that belongs to the very being of the planet. It comes into existence

through us—on one level it is the light of humanity, both individually and collectively—and through the physical body of the planet, though it does not

belong to the physical dimension; it is fully alive on the inner planes, in a dimension where its light is clearly visible; but it is also the living,

sacred essence of the physical world we know, alive in every cell of creation.

In the inner worlds, the light of the world soul is guided by the masters of love; in the outer world it needs our conscious attention. And because this

light is not other than our light, we can access it through the light of our own higher nature—which means that we can access it wherever we are, in any

situation. Working with our own light, through attention and remembrance, our higher consciousness can directly participate with the light of the whole,

and we can make a direct contribution to the way the light moves around the planet. And when the light of the soul of the world begins to flow, it can

reveal to humanity to our divine potential and the deeper meaning of life. There are specific ways we can learn to work with it—ways for the light to

interact with the darkness of the world and transform this darkness, to reveal hidden qualities within humanity and awaken life to its magical and

miraculous nature. It is this light that can transform creation and welcome the Beloved back into His world.

All who are open to this work are needed to participate, and each of us can contribute in our own way, according to our nature. But part of this work can

only be done by women. They carry the sacred substance of life in their spiritual centers. Without this light a woman could not conceive and give birth,

she could not participate in the greatest mystery of bringing a soul into life: giving the spiritual light of a soul a physical form out of the substance

of her own body. Women instinctively know how to bring spirit into matter and awaken the spiritual potential of matter.

The awakening of the soul of the world is also an awakening to the interconnectedness of all of life and to life’s own healing potential that works through

its interrelatedness. Women, carrying within them a spiritual connection to life that is not present in men, instinctively understand life in its wholeness

as a living web of relationships and connections through which life’s energy flows. They carry these connections in their physical and spiritual bodies in

a way that is foreign to men. Women’s natural attunement to the divine as it manifests through the whole, interwoven, living tissue of creation is

essential to the healing and transformation of life, and only women can bring this dimension to the work.

Women have to recognize their true spiritual nature and the transformative potential they carry within them, so that they can offer it back to life—for

without its light the world will slowly die. Women carry within them the light that can heal the split between matter and spirit that has done such damage,

causing the physical world to forget its sacred nature and its ability to transform and heal itself. Life itself has become caught in the abusive

thought-forms of the masculine that denigrate the feminine and seek to dominate through power. The light within women is needed to free life of theses

constrictions and abuses, and to reconnect matter once again to its spiritual potential. For a woman the physical and spiritual worlds can never be

separate: she carries the light of the world within the cells of her body; her sexuality is a sacred offering to the goddess. But she needs to consciously

recognize this divine potential and deep knowing, so that she can live it in service to life and the need of the time. The world needs the presence of

women who are awake to their spiritual light, and who can work with the substance of life in order to heal and transform it.

In the work with the soul of the world we are guided from within by the awiliya, the masters of love, but we each need to take responsibility for

our own light, for bringing our light into our life and into the world. We need to look beyond our own individual spiritual journey to offer our light for

the healing and transformation of the world. Once we realize that our light is part of the light of the whole, we will be able to participate more fully in

this work of co-creating the future, in helping the world awaken from its nightmare of forgetfulness so that it can remember and celebrate its divine

nature.

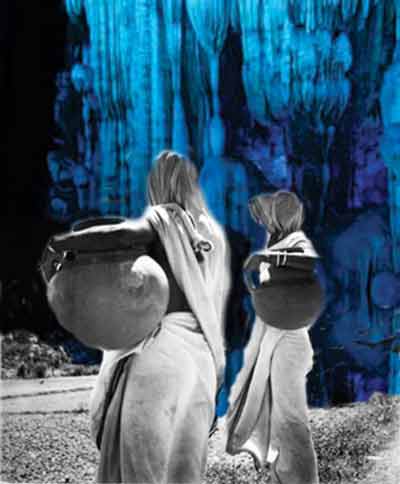

Women carrying water. art by Anat Vaughan-Lee

THE WORK OF THE PATH

The Naqshbandi path of the masters is like a river, sometimes visible, sometimes hidden underground. It appears where it is needed, where there is

spiritual work to be done. Although the outer form may change, its inner essence remains unchanged. It is a spiritual system designed to transform a human

being, to awaken us to our divine nature and teach us how to live this in service to our Beloved, according to the need of the time.

On the path there are different forms of spiritual work. Inner purification is an important preliminary work, involving changing the patterns of our

behavior and freeing ourselves from attitudes and responses that interfere with our aspirations. Psychological inner work is part of this

process—confronting the “shadow,” the repressed, rejected and unacknowledged parts of our psyche; accepting our wounds; and transforming psychological

dynamics and patterns of conditioning. Through spiritual work we also develop the qualities we need for the path, for example self-discipline, compassion,

patience, perseverance. In particular we learn to value the feminine qualities of receptivity, listening, and inner attention. Through working on our

spiritual practices such as meditation and remembrance, we learn to still the mind and be attentive to the needs of the divine in our inner and outer life.

We also learn to master our negative qualities, such as anger, greed, jealousy, and judgment. Through this work we are better able to align ourselves with

our higher nature and live its qualities in our daily life. We bring our selflessness, awareness, loving-kindness, discrimination, and other qualities into

our family and workplace, transforming both ourselves and our environment. To live according to our higher principles in the midst of the outer world with

its distractions and demands is a full-time work.

The spiritual wayfarer gives herself to her inner work and outer service. The Sufis are known as “slaves of the one and servants of the many.” We make our

contributions to outer life in whatever way we are called, whether through simple acts of loving-kindness or more defined service helping those in need. We

help those in our spiritual community and daily life. We learn to be always attentive to the needs of our Beloved in whatever form He appears.

And there is also another dimension of spiritual work that until now has been mainly hidden, known only to initiates. This is the work done by individuals

and spiritual groups on the inner planes, helping humanity from within. At this time there is a real need for all those who have awakened to their

spiritual nature to participate as fully as they are able, to work with the light of the world in service to the whole—to help the soul of the world awaken

so that the wonder and joy of divine presence can again nourish everyday life. This is a simple but demanding work, the work of love and remembrance, of

being fully present in our life and allowing our light and attention to be used by the masters of love.

And always we are held in the presence of our sheikh and the transmission of love passed from teacher to disciple: the grace that is given

effortlessly, the love, light and protection that come from the succession of those who are merged in God.