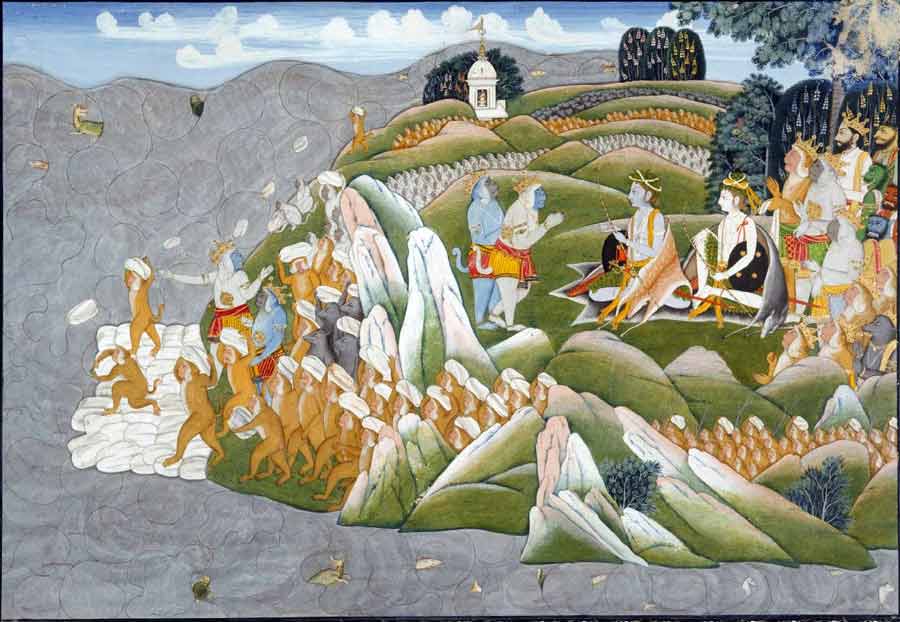

Monkeys and Bears building Ram Setu - Kangra, Himachal Pradesh (Philadelphia Museum of Art) 1850

I

What could Pāṇini, perhaps the greatest grammarian of all time, have to do with Bharata Muni and his theories of art, drama and music? But speaking of

grammar in the same breath as art is not as incongruous as one thinks when it is noted that both language and creations of art are governed by rules and

conventions. The challenge in each is to express meaning and feeling in new creative ways, and both Pāṇini and Bharata indicate that at the basis of their

productions lies the universal which is, therefore, a means to the knowledge of the self.

Pāṇini's grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, described in nearly 4,000 sūtras the rules to generate all Sanskrit sentences and he collected roots in the dhātupāṭha

and primitive nominal stems in the gaṇapāṭha. The Aṣṭādhyāyī is a wonderful resource for the culture and history of his times and it mentions the Naṭasūtra

of Śilālin, which was the canonical text on drama in his times.

Pāṇini, by the very beauty, complexity and exhaustiveness of his rules, presaged similar efforts at complete classification in the fields of art and

architecture. In this he was following an old model, in which the central results of a science are expressed in terms of sūtras, which in turn require

vṛtti (turning the sutras into fully worded paraphrase) and bhāṣya (commentary) for complete explanation. Before Pāṇini’s time this was already in place

for the six great darśanas of Indian philosophy with their corresponding sutra texts.

Bharata Muni's Nāṭyaśāstra (sometimes called the fifth Veda), which appeared not too long after Pāṇini, classified the diverse arts that are embodied in

the classical Indian concept of the drama, including dance, music, poetics, and general aesthetics. Later, the Bṛhatsaṃhitā of Varāhamihira (505-587 CE)

and the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa of the 4th century CE[1] describe canonical conventions of architecture, iconography, and painting.

Behind the rules of grammar was the idea clearly expressed in the Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad that all linguistic thought or representation can only hope to

approximate reality which, in its deepest levels is transcendent (parā). The success of the poet and the artist owes not to the canonical rules

and conventions of the medium (surface structure) but rather to the inexpressible intuition behind the conception (deep structure)[2].

The artist strives to represent the divinity or communicate its spirit through the artistic creation, so that the aesthete might get connected to his or

her own divinity within them. The beginnings of this in the Vedic ritual were in terms of representing the cosmos in the fire altar which, later, became

the model for the temple[3], fine arts and music[4]. Pāṇini’s work falls quite within the framework of the Vedic tradition for he took the earlier

Pratiśākhya rules on converting the word-for-word recitation of the Veda into a continuous recitation and created an abstract grammar of unsurpassed power.

In the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa, the sage Mārkaṇḍeya says that although divinity is formless, worship and meditation are possible only when it is endowed

with form. Therefore, the artist observes nature carefully and molds that inspiration using the conventions that he has internalized in the realm of his

imagination.

The model for the creative sciences in India is the churning of the ocean (samudramanthana) that occurs within the heart of the artist. This is a

dance between mechanicity and freedom, represented respectively by the demons and the gods, out of which new vision and insight.

The creative process depends on rules and precepts but the artist must reach for a deeper understanding that helps him recognize the authentic and the

meaningful, just as the poet cannot depend on the rules of grammar alone to find words that communicate felt experience. The driving force must thus be the

transcendent self which informs the mechanistic mind.

Dākṣīputra Pāṇini

II

Dākṣīputra Pāṇini was born in Śalātura in northwest India, north of the confluence of the Sindhu and the Kabul rivers. According to tradition, he became a

friend of the king Mahānanda of Magadha (5th century BCE). The Kathā-sarit-sāgara of Somadeva (11th century) mentions that Pāṇini's teacher was Varṣa and

his rival was Kātyāyana. The Aṣṭādhyāyī appears to supersede an earlier Aindra grammar. Xuanzang (Hieun Tsang) in the 7th century visited Śalātura and

found that the grammatical tradition was continued there and that Pāṇini had been honored with a statue[5], [6].

Pāṇini's grammar along with its word-lists, presents invaluable incidental information about life and society in the 5th century BCE India. It provides us

names of cities, towns, villages and cultural and political entities called Janapadas, details regarding social life, economic conditions, education and

learning, religion, and political conditions.

The Janapada states had different kinds of government. Some Janapadas were republics, others were monarchies. We learn that the king did not have absolute

power and he shared authority with his minister. This balancing of the powers created an environment that was conducive for questioning out of which

emerged the many sciences that have come down to us.

Pāṇini’s references shed important light on the way religion was practiced. We find that images were used to represent deities in temples and open shrines.

There were images in the possession of the custodian of shrines. The Mahābhāṣya, the second century BCE commentary on Pāṇini’s grammar describes temples of

Dhanapati, Rāma, Kṛṣṇa, Śiva, and Viṣṇu.

Pāṇini is aware of the Vedic literature and the Upaniṣads. He also knows the Mahābhārata. Pāṇini's work is thus invaluable in the dating of the texts of

the Vedic period. Pāṇini describes coins that came prior to the period of Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra (4th century BCE). Pāṇini appears to have traveled to

Pātaliputra to participate in a great annual meeting of scholars.

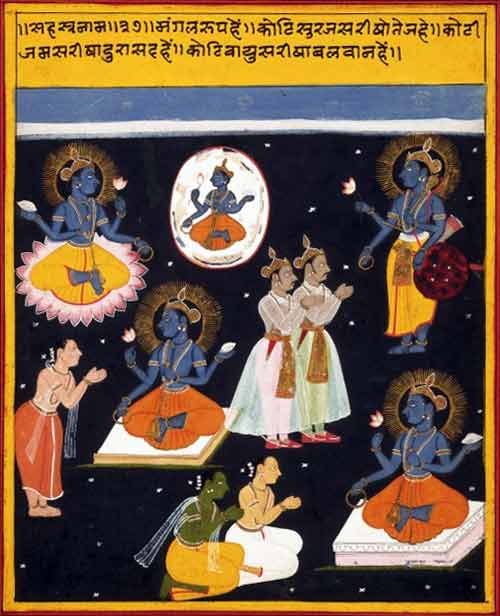

Vishnu sahasranama manuscript, ca 1690. Vishnu being worshipped in his five forms,

including Rama and Lakshmana. Opaque watercolour on paper,

Mewar, India. Date circa 1690 Source V&A Museum

III

What the Aṣṭādhyāyī is to language, the Nāṭyaśāstra is to the artist and the musician[7]. The structure of Indian classical music and dance was added to

by Mataṅga Muni's Bṛhaddeśi (about 600 CE), Abhinavagupta's Abhinavabhāratī and Śārṅgadeva's Sangīta Ratnākara (13th century). This connection with the

tradition has continued in the Hindustani Saṅgīta Paddhati by Vishnu Nārāyaṇa Bhāṭkhaṇḍe from the early 20th century.

Bharata explains the relationship between the bhāvas, the emotions evoked in the spectators, and the rasa, essence of the performance or

the work of art. He says that the artist should be conscious of the bhāva and the rasa that is being sought to be established. The word rasa itself means

“juice” and it is seen as emerging from the interplay of vibhāva (stimulus that may be a word or a gesture), anubhāva (reaction) and vyabhicārī bhāva

(fleeting or transitory emotion). A performance that is technically correct but has no emotion would be said to be wanting in rasa. According to

Abhinavagupta, rasa is a universal mental state and the highest purpose of all creative arts is to help the connoisseur reach such a state, for the arts

are the aesthetic means to knowing the self.

Bharata explains rasa by giving the parallel of the combination of various condiments, each having its own taste, which creates a unique taste that

lingers. The corresponding combination in drama leads to a feeling (sthāyībhāva) that is the nāṭyarasa. In both these cases, the subject, whose mind

reflects cultural and personal experience, is central to the appreciation of the creation.

The eight sthāyibhāvas are rati (love), hāsa (mirth), krodha (anger), śoka (grief), utsāha (heroism), bhaya (fear), jugupsā (disgust), and vismaya

(wonder). Corresponding to these are the eight rasas of the Nāṭyaśāstra that form four pairs:

i. śṛngāra, love, devotion. Color: dark hue.

ii. hāsya, laughter, mirth. Color: white.

iii. raudra, fury, anger. Color: red.

iv. kāruṇya, compassion, sadness. Color: dove colored.

v. vīra, heroism, courage. Color: yellowish.

vi. bhayānaka, fear, terror. Color: dark.

vii. bībhatsa, repulsion, aversion. Color: blue

viii. adbhuta, wonder, astonishment. Color: yellow

The deities associated with these are Viṣṇu, Pramatha, Rudra, Yama, Indra, Kāla, Mahākala, and Brahmā, respectively. Later, the sages accepted a ninth rasa śānta, peace or tranquility, with the color of white and Viṣṇu as deity, and the expression navarasa (the nine rasas) became

popular. Nāṭya is a sharpened representation of life wherein the various emotions are dramatically enhanced so that the spectator gains the flavor of the

portrayed pleasure and pain taking him to the source of this within himself.

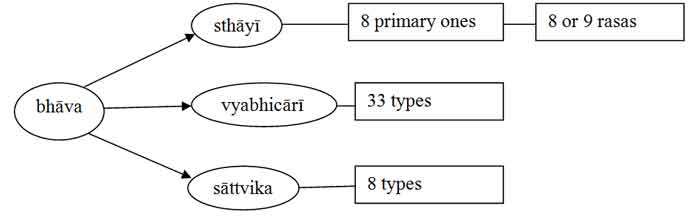

Bhāvas and rasas

There are three types of bhāva, namely sthāyī (eight types), vyabhicārī (thirty-three), and sattvika (eight), for a total of forty-nine. The eight sthāyī

bhavas are the bases of the eight rasas.

The vyabhicārī bhāvas are:

|

1. nirveda (depression, caused by abuse, censure, and so on)

|

2. glāni (languor, result of hurt, emptiness, illness, and so on)

|

3. śaṅkā (suspicion)

|

|

4. asūyā (jealousy)

|

5. mada (intoxication)

|

6. śrama (fatigue)

|

|

7. ālasya (laziness)

|

8. dainya (misery)

|

9. cintā (anxiety)

|

|

10. moha (fainting, caused by ill luck, calamity)

|

11. smṛti (memory)

|

12. dhṛti (fortitude)

|

|

13. vrīḍā (sense of shame)

|

14. capalatā (nervousness)

|

15. harṣa (joy)

|

|

16. āvega (agitation or excitement)

|

17. jaḍatā (slothfulness)

|

18. garva (pride)

|

|

19. viṣāda (sorrow)

|

20. autsukya (unease arising from remembrance of a dear one or a beautiful place)

|

21. nidrā (sleepiness)

|

|

22. apasmāra (forgetfulness)

|

23. supta (overcome by sleep)

|

24. vibodha (awakening)

|

|

25. amarṣa (intolerance)

|

26. avahittham (dissimulation)

|

27. ugratā (fierceness)

|

|

28. mati (understanding)

|

29. vyādhai (illness)

|

30. unmāda (insanity)

|

|

31. maraṇam (death)

|

32. trāsa (dread)

|

33. vitarka (argumentation)

|

The sāttvika bhāvas are the physical manifestation of genuine emotion. They are:

a. stambha (stupefaction),

b. sveda (perspiration),

c. romāñca (thrill),

d. svarabheda (voice change),

e. vepathu (trembling),

f. vaivarṇya (facial color change),

g. aśru (tears),

h. pralaya (swoon, fainting).

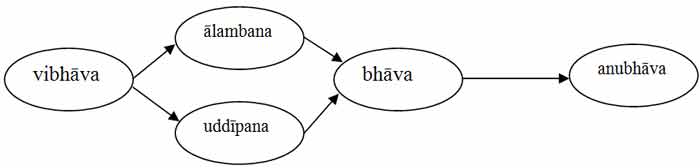

From stimulus to emotion and subsequent reaction

Vibhāva as the cause has two fundamental components: the ālambana vibhāva which is the basic stimulant and the uddīpana vibhāva which is the enhancing

stimulant related to the environment and the context. If the heroine is the ālambana vibhāva, the location, like a garden, is the uddīpana vibhāva.

Abhinavagupta asks the question whether nāṭya is representation of reality (tattva) or its likeness (sadṛṣya) as in the case of a twin, or mere error

(bhrānti) as in the case of silver being taken as a piece of mother-of-pearl, or superimposition (āropa), or as replica (pratikṛti) as in the case

of a painting of a model, and so on. He asserts that nāṭya is neither of these for each of these lacks transcendence (asādhāraṇatā) without which there

cannot be rasa.

The aesthetic experience is a doorway to the innate dispositions of the self for in that moment the connoisseur has become more than just his own self. In

the contemplation of characters depicted in the work of art, or in the absorption in an abstract composition, the mind feels the breath of the universal

spirit.

Rigveda manuscript

IV

Let me now briefly speak of the impact of these ideas. Pāṇini’s work, in particular, and Sanskrit grammar, in general, showed the way to the development of

modern linguistics through the efforts of scholars such as Franz Bopp, Ferdinand de Saussure, Leonard Bloomfield, and Roman Jakobson. Bopp was a pioneering

scholar of the comparative grammars of Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages. Ferdinand de Saussure wrote his Ph.D. on De l'emploi du génitif absolu en Sanscrit (1880) and lectured on Sanskrit in Paris and Geneva. In his most influential work, Course in General

Linguistics (Cours de linguistique générale), that was published posthumously (1916), he took the idea of the use of formal rules of Sanskrit

grammar and applied them to general linguistic phenomena. Bloomfield, having studied Pāṇini, contributed much to structural linguistics, applying these

ideas not only to Indo-European historical linguistics but also to Austronesian and native American languages.

Roman Jakobson, who died in 1962, contributed to the development of the structural analysis of language, and eventually these ideas were applied to

disciplines beyond linguistics, such as anthropology and literary theory. Modern linguistics seeks not only to determine the type of a language but also

its specific characteristics and linguistic universals is the study of the general features of languages in the world.

The structure of Pāṇini‘s grammar contains a meta-language, meta-rules, and other technical devices that make this system effectively equivalent to the

most powerful computing machine. Although it didn’t directly contribute to the development of computer languages, it influenced linguistics and

mathematical logic which, in turn, gave birth to computer science.

The works of Pāṇini and Bharata Muni also presage the modern field of semiotics which is the study of signs and symbols as a significant part of

communications. Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra has much material on acting, signs, gestures, and posture each one of which communicates its own specific meaning to

the spectator.

The search for universal laws of grammar underlying the diversity of languages is ultimately an exploration of the very nature of the human mind. The other

side to this grammar is the idea that a formal system cannot describe reality completely since it leaves out the self. As human society evolves, signs and

symbols in use lose their original meaning, manners change, and fashions come and go.