Temple Sculpture Representing Ganesha and His Spouse with two female attendants beyond the columns, India, Madhya Pradesh, 12th century Sandstone Cat. 103.

God as Yogi

The earliest evidence for yoga is found not in texts but rather in art, in the material remains of the Indus, or Harappan, civilization. Much later it was

this renunciate /ascetic tradition that was predominant in the philosophical literature known collectively as Upanishad, out of which—and in antagonism to

Vedic sacrificial rituals—emerged Jainism and Buddhism, as well as theistic Hinduism. The geographic source of this thought process, however, belonged far

to the east of the sites of the Harappan civilization: in the lower Gangetic plains and largely among the warrior class known as kshatriya, rather

than among the higher priestly class of brahman (adopted in English as Brahmin with a capital B as in “Boston Brahmins”). [1]

Both Vardhamana Mahavira and Buddha Shakyamuni belonged to the kshatriya class, as did many of the Upanishadic teachers and

thinkers themselves. Both renounced the life of a householder and took to the road in search of enlightenment, practiced austerities, and adopted yogic

meditation as the means of attaining liberation (moksha, kaivalya, nirvana, etc.).

Fig. 13 Detail of stone fragment showing worship of meditating Buddha Shakyamuni, Uttar Pradesh, 2nd century. Cat. 150.

Fig. 14 Detail of stone stele of Jina Parshvanatha seated in yogic posture, Karnataka, 13th century. Cat. 117.

Accordingly the earliest figures of Buddha and the Jina are both represented without earthly trappings and as ideal yogis and monks (fig. 13, cat. 150;

fig. 14, cat. 117). In keeping with the greater emphasis on renunciation in Jainism, the Jina is either scantily attired or completely naked, while the

Buddha is clad in three pieces of monastic garb. Indeed, as noted above, this sartorial issue caused a fissure within the Jain community, which is why

early representations of the Jinas (down to the 6th century ce) demonstrate the utter disdain, befitting the liberated Jina, for any form of materiality

and sensuality. [2]

Fig. 15 Stone image of Bhairava, Tamil Nadu,

14th–15th century. Cat. 77.

The image of the Jina in Indian art is the most spiritual, abstract, and detached in the contextuality of human form. Indeed,

even in the earlier art of the pre-Buddhist and -Jain period, whether male or female, the human figure is never conceived as realistic or physically ideal

as in Greek sculpture. Rather, it is depicted with a looser body and more flexible limbs and smooth flesh in keeping with the body of a yogi, which is

never muscle-bound and taut. The difference is easily perceptible by comparing a Gandhara and a Mathura Buddha image (see cats. 150 and 151).

Less stylized

and more sensuous than the Jina statue, the Buddha figure is characterized by a much greater diversity of gestures and postures. In early art, the Buddha

is still a historical person, and important life events are never forgotten, being subtly alluded to with hand gestures. In the many forms of the

transcendental Buddhas of later Buddhism as the religion became elaborate, the traces of historicity were abandoned in favor of symbolic meaning.

Iconographic variations are much greater in Buddha images than in those of Jinas, but no matter how they are distinguished from ordinary mortals with

extrasensory bodily signs of a mahapurusha (a great person) and divinized with provision of a nimbus or halo, they are never given multiple arms

and hands, which is one of the most indisputable methods of distinguishing the divine from the mortal in the Indian mythic mind.

Fig. 16 Vishnu on Garuda (detail), Karnataka, early 19th century. Cat. 20.

In the Hindu pantheon, the God Shiva is the ascetic yogi par excellence, but his images, even in the limited examples in the exhibition, reflect an

enormous variety of forms (cats. 66–78). The most notable iconographic feature of his renunciate character is of course his matted hair, yet he is

portrayed as a handsome youth. His third eye on the forehead, the source of his cosmic rage and energy, is not always present. By and large, he is

conceived as a combination of a householder, frequently with his spouse Parvati, or Uma (who, like him, assumes wrathful forms as required), and a

renunciate. Even in his angry or Bhairava form (cat. 74; fig. 15, cat. 77), he does not lose his youthfulness.

The concept of yoga is also closely associated with the God Vishnu as in such iconographic forms as Yogavishnu, Yoganarasimha, and Yognarayana. In fact, as

early as the Mahabharata, in the story of the sojourn and conversation in the Himalayan ashram called Badari between Nara (Man) and Narayana (one who inheres in Man), both are represented as yogis, as they also are in art. [3] Narayana is also the name of the supreme form of Vishnu in the Pancharatra belief system (a

highly ascetic branch of Vaishnavism), and in his recumbent image in the cosmic ocean on a couch formed by the cosmic serpent Ananta (Eternity), he is said

to be in yoganidra, or meditative sleep (cat. 21). The pervasive influence of yoga is also encountered with the Devi or Durga such as Yogamaya (maya meaning “illusion”).

Fig. 17 Detail of arch above Vishnu image showing Brahma, Shiva, and Dashavatara, Rajasthan, ca. 11th century. Cat. 15.

God as Ruler and Protector

Apart from the yogi, the mendicant, or the ascetic, the earthly ruler or the king, too, served as a model for the Gods of Indian mythologies from ancient

times. The Vedic Indra, powerful king of the Gods, was given the elephant as his mount, the most enduring symbol of regal grandeur on the subcontinent.

When the Greek conqueror Alexander confronted King Puru (Greek Porus) in the Punjab, the Indian ruler charged into battle on his elephant. Emulating most

Indian kings, subsequent conquerors who settled in the country, notably the Mughals and the British, adopted the pachyderm as the most appropriate symbol

of imperial pomp and circumstance.

For the Hindus, Vishnu was the model of earthly rulers, and his representation was modeled on that of a king with every

royal accoutrement. In fact, one of his epithets is Upendra, or Little Indra, the king of the Gods; he is also a Sun God and hence he rides the solar bird

Garuda to survey the universe (fig. 16, cat. 20) and preserve cosmic order. Appropriately, his spouse is Lakshmi, the Goddess of good fortune, wealth, and

prosperity, which are all essential for a successful ruler. In eastern India, he was further provided with a second consort in Sarasvati, the Goddess of

wisdom, who in the South is Bhudevi, or the personified earth—and hence bhupal (protector of the earth) is a synonym for king.

Fig. 18 Balarama as the eighth avatar of Vishnu, Madhya Pradesh, 11th century. Cat. 31.

Fig. 19 Buddha as the ninth avatar of Vishnu, Madhya Pradesh, 11th century. Cat. 42.

As the Cosmic

Preserver, not only does Vishnu riding on Garuda roam the universe, but to save the world and his devotees or to restore moral order, he also periodically

descends (avatirna) to earth as an avatar. By the Gupta period, a group of ten avatars (Dashavatara) came to be especially recognized. The

exhibition includes a relief of Vishnu with all ten avatars represented together around the lotus halo (fig. 17, cat. 15). Two sandstone sculptures in the

museum’s collection depicting Balarama (fig. 18, cat. 31) and the Buddha (fig. 19, cat. 42), the eighth and ninth avatars, respectively, are well known and

rare examples of what must have been an impressive series of sculptures for a Dashavatara temple.

Buddha is the only certain historical figure among the ten, the last, Kalki, being still awaited. [4] It is an exemplar of the tolerant attitude

of the Hindus that they adopted as a divine incarnation the founder of what they otherwise consistently characterize in the Puranic literature as a heretic

religion. Significantly, Mahavira was not so honored, probably because of the extremism of Jain beliefs as well as the larger following of Buddhism at the

time, but Rishabhanatha was accepted as a minor avatar of Vishnu. The Jains further adore Krishna, who is said to be a cousin of the twenty-second Jina

Neminatha. Ironically, however, it was Buddhism that later lost its popularity in the Indian subcontinent, while Jainism still survives harmoniously with

its identity intact. [5]

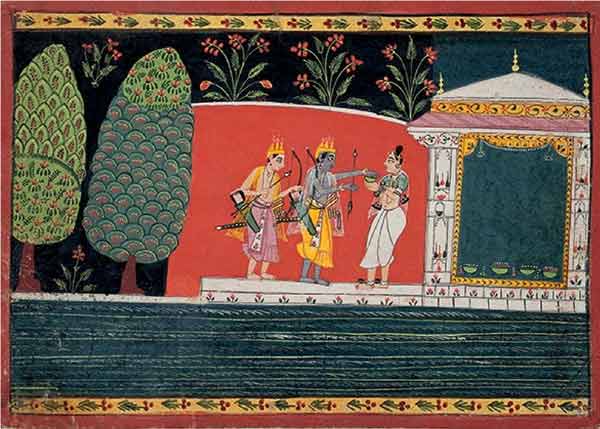

Fig. 21 Krishna as seen by Arjuna in his cosmic form,

Rajasthan or Gujarat, 19th century. Cat. 54.

Among the other avatars, the exhibition includes several representations of Narasimha, the Man-Lion (see cats. 27–30), and of Rama, the hero of the epic Ramayana (fig. 20, cat. 35; see also cats. 36 and 37). It should be noted that most Hindus believe Rama was a historical figure and an ideal

ruler; the expression Ramrajya (the rule of Rama) has come to mean good governance. In the Tanjore reverse glass painting, the only example of the

technique introduced in India in the 18th century by immigrant Chinese artists, we glimpse a view of the ideal court of Rama. Flanking the green Rama and

the fair Sita are Lakshmana displaying humility with crossed arms and a diminutive Hanuman (also green) in the attitude of devotion with his tail hanging

down between his legs (cat. 36). The influence of a modern formal photographic portrait is evident.

Even though Shiva is the archetypal ascetic God and the

primal yogi, his hair is arranged in a jatamukuta (crown [mukuta] of matted hair). A tiger skin drapes his hips, and human skulls and

serpents are his ornaments; yet, despite these symbols of asceticism, he is often shown bedecked in jewelry as befitting a king. The exhibition includes a

variety of his representations from different periods that reflect his diverse imagery, the simplest being his symbolic form in a linga (literally

“sign” and likely a word of non-Sanskrit origin), signifying both his generative organ and a cosmic pillar, while others are anthropomorphic and mythic

figures (see cats. 61–63). Most of Shiva’s forms are pacific, but in some he is presented in his angry manifestation known as Bhairava, a later variation

of Rudra of Vedic literature (see fig. 15). Here he is the Cosmic Destroyer of the Puranic triad where Brahma is the Creator and Vishnu the Preserver.

No

one who has witnessed religious processions or gaily dressed statutes in Catholic Latin America will be surprised to see the wide use of additional

clothing for the principal deities in Hindu temples and shrines, public and domestic. Indeed, the most suitable expression of this dressage would be

“regal,” both for the materials used and for the adornments, sometimes so profuse that only the deity’s eyes may be visible to the eager devotee. To

complete the regal imagery, a tiara or crown is often added, even when the sculpted or modeled head beneath is already embellished. Generally, however, it

is more common to use a piece of plain red cotton garment on the figure in Hindu temples, while a yellow piece drapes a Buddha and the Shvetambara Jains

employ a length of white cloth.

Just as the Sanskrit word bhagavan (possessor of fortune or share) is freely used by the Hindus to characterize

Gods, so, too, the Jains and Buddhists honor their liberated teachers by the same qualifier, such as Bhagavan Buddha or Bhagavan Mahavira. In a similar

fashion, the expression maharaja or maharaj (great king) is a common form of honorific address for both holy men and divinities by the

followers of all three faiths.

The spiritual majesty of the Buddha is emphasized in early Buddhist texts when he was declared the “King of Righteousness.”

While the early representations of the historical Buddha are not literally crowned, the seat is a lion-throne (simhasana). In later Vajrayana

ritual, it became obligatory to represent the “body of bliss” (sambhogakaya) suitably adorned and crowned. Tantric initiatory rites for spiritual

transformation are similar to royal consecration ceremonies. [6] The Jains, in due course, adopted similar abhisheka or initiatory rites

and embellished the abstract, stylized images of their liberated or omniscient teachers with trappings of kingship, such as the triple umbrella above, the

flywhisks held by attendants, and lustrating elephants (cats. 126 and 127). Finally, the last sermon of the liberated being in the Hall of Universal

Sermon, or the samavasarana, is conceived as a grand audience or durbar as befits a universal monarch (cat. 124).

Fig. 20 Rama and Lashmana approach a hermitage, Malwa, ca. 1680s. Cat. 35.

The Eminence of Krishna

Fig. 22 An infant Krishna cradling a butter ball,

Tamil Nadu, 16th century. Cat. 43.

The most complex and charismatic Vaishnava, or even Hindu, deity represented in the exhibition is Krishna. He is the friend, counselor, and charioteer of

Arjuna of the epic Mahabharata, for whom he brilliantly summarizes on the battlefield of Kurukshetra the essence of Hindu philosophy and theology

in a poem called the Bhagavadgita that has become globally famous today. In a remarkable Rajput painting in the exhibition, we encounter Krishna’s Vishvarupa, or Universal Form; when to convince Arjuna, he demonstrates that everything in the universe owes its origins to him (fig. 21, cat.

54). To enable Arjuna to behold this awesome cosmic form, Krishna gives him divine sight, literally yogamishvaram, or yogic empowerment. [7] Clearly, here Krishna resorts to a visual image when he is unable to persuade Arjuna with lengthy rhetoric.

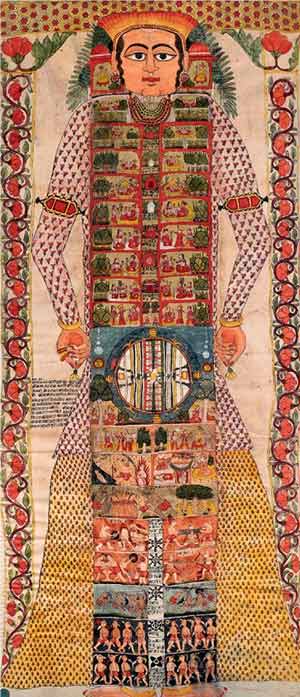

Fig. 25 Lokapurusha, Cosmic Man,

Gujarat or Rajasthan,

18th–19th century. Cat. 137.

The Bhagavadgita is believed to have been composed about the time the earliest objects included in this exhibition were made, and advocates

several ways to salvation, one of which is the path of yoga, already discussed, and another that of bhakti or devotion, which is expressed through puja and

piety. Interestingly, while presenting the brief for war involving violence, the philosopher-God exhorts Arjuna that for personal salvation, unwavering

faith in him, or for that matter any other deity, is a desideratum. [8] This steadfast devotion also forms the crux of some of the avatar myths,

such as that of Narasimha, when the boy devotee Prahlada is saved while the doubting Thomas of a king, Hiranyakashipu, is destroyed. A graphic work in the

exhibition further demonstrates the theme of bhakti when Vishnu appears before another young devotee called Dhruva or Steadfast (cat. 17).

In the early and

traditional group of ten avatars, at least until the 12th century, Krishna is excluded in favor of his foster brother, Balarama. Both, however, were humble

cowherders of Vrindavan rather than the kshatriya prince of Dwarka, who counseled Arjuna in the battlefield. It is this dark cowherder lad who is the

flute-playing darling of the cowherder girls, scourge of the evil ruler Kamsa of nearby Mathura (whom he finally destroys though he does not sit on the

throne himself), and, ultimately, the great lover of the singular cowherder girl Radha, who became the focus of popular devotion across the subcontinent.

Krishna is also the most popular figure among the exhibits. His adventurous and mischievous feats have inspired generations of artists to sculpt or paint

innumerable representations with both imagination and emotional intensity. No other Hindu deity embodies love in all its major psychological states with

such perception and empathy. One can worship him as a mischievous crawling infant with a butter ball (fig. 22, cat. 43), a dancing toddler (fig. 23, cat.

44), or an adolescent hero (fig. 24, cat. 47)—a youthful flute-player enchanting the cowherder girls, which became the favorite image of the God during the

last five centuries of the millennium, especially in northern India. The exhibition includes multiple depictions of this form of Krishna—an extraordinary,

richly carved, large wooden panel from Odisha, which may have been used as a temple door (see fig. 34, cat. 48), as well as stone and metal images intended

for domestic shrines (see cats. 45–47).

Fig. 23 A dancing toddler Krishna, Tamil Nadu, 17th century. Cat. 44.

Fig. 24 A cosmic six-armed flute-playing Krishna, Odisha or Bengal, 19th century. Cat. 47.

Devotional Paintings

No deity has inspired and influenced the art of painting as ubiquitously as Krishna, as is clear from the number and diversity of pictures of this God in

the exhibition. Also included are a few devotional pictures created in the 19th century around the famous Kali temple in Kolkata in a distinctive style

that has come to be known as the Kalighat school (see cats. 32, 52, and 53). While these freely limned images were popular with pilgrims, the school also

delineated contemporary societal and satirical themes that were popular with visitors both native and foreign. Buddhists also produced vast quantities of

portable paintings on cloth and paper at their monasteries and shrines, which have not survived in India but were preserved in Nepal and Tibet, where they

strongly influenced local pictorial traditions.

However, the oldest surviving paintings on cloth in India are those commissioned by the Jains. [9] Several Jain paintings of different sizes and

periods are included in the exhibition and are discussed by John Cort in his essay, but a few additional comments here would not be out of place. The Jain

pictorial works in the exhibition not only show remarkable diversity of size, medium, and subject, but serendipitously help us to understand the history of

Indian painting over four centuries. They include manuscript illustrations on paper that, in the distinctive style of western India, depict in miniature

the stereotypical narrative of the lives of the Jinas and teachers (cats. 134 and 135), as well as monumental paintings on cloth or paper with

cosmographical or cosmological themes (cats. 121 and 122) and complex topographical compositions of famous pilgrimage sites such as Shatrunjaya (cat. 139).

There is also an abstract, modernist picture of Lokapurusha, or Cosmic Man (fig. 25, cat. 137) corresponding to the

Vishvarupa of the Bhagavadgita discussed above (see fig. 21, cat. 54). The cosmographical pictures are the only survivals of the ancient tradition

of mandala painting, lost on the subcontinent but enduring elsewhere in Asia. In fact, the exhibition includes rare three-dimensional examples of Jain

mandalas in stone and metal (cats. 118–120).

Fig. 26 Shrinathji, the form of Krishna worshipped at Nathdvara,

Rajasthan, 19th– 20th century. Cat. 56.

Such large paintings were also produced by the Vaishnavas, who lived in the same geographic and cultural zone

as the Jains in western India and in the Vaishnava stronghold in Odisha on the east coast. A number and variety of objects in the exhibition are from two

leading centers of Krishna worship: Puri in the state of Odisha and Nathdvara in the desert state of Rajasthan. Both are important pilgrimage sites for

devout Vaishnavas and are visited annually by millions of pilgrims.

The Puri temple dedicated to Jagannath (Lord of the World) is the older shrine, while

Nathdvara was established in the 16th century by the charismatic philosopher-teacher Vallabhacharya (active 1481–1533). Both temples have had enormous

influence among Hindu courts and communities far beyond their location. Arts created for devotees and pilgrims at the two centers have influenced

devotional imagery elsewhere. Several of the Nathdvara style of monumental paintings with diverse subjects and forms reflect with visual panache the glory

of Krishna’s divine splendor (fig. 26, cat. 56), while the select smaller examples on paper in a wide variety of styles with narrative content as well as

literary conceits depict what is characterized in literature as Krishnalila, or the Divine Play of Krishna.

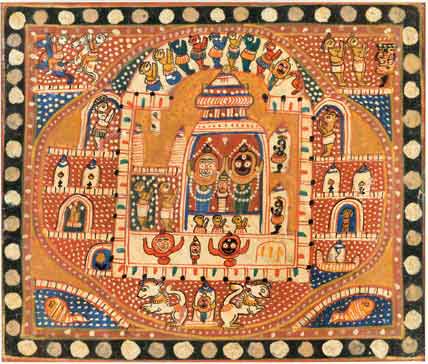

Fig. 27 The Jagannath temple triad, Odisha, late 19th–20th century. Cat. 34.

The Jagannath temple of Puri is an ancient

shrine of even greater antiquity than the current impressive 13th-century temple complex visited by countless Hindu pilgrims. Consisting of a triad, the

deities are identified as Krishna as Jagannath, his brother, Balabhadra (Balarama), and their sister, Subhadra, a manifestation of the great Goddess. Even

their iconographic representations (cat. 33; fig. 27, cat. 34) are unusual to say the least: they reflect a tribal aesthetic and are among the most exotic

and geometric forms used in a major Hindu temple. It should be mentioned that not only do local tribal communities participate in the temple ritual but

every twelve years the timber images in the main shrine are replaced with freshly carved examples intended to be impermanent, whereas most principal images

in temples of all three religions are created of stone or metal for greater permanence.

In both paintings, besides the triad, the ten avatars are included

as in the much earlier stele from the west (see fig. 17, cat. 15), but here the Buddha is replaced by Krishna as Jagannath. This must have happened after

Jayadeva, for in his (ca. 12th century) lyrical Sanskrit poem Gitagovinda (sung daily at the Puri temple), the poet retains Buddha in his

beautiful invocatory eulogy to the ten avatars; “moved by deep compassion,” he “condemned the Vedic way that ordains animal slaughter in rites of

sacrifice.” [10]