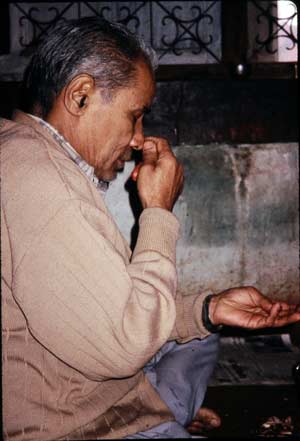

Priest of Patan Royal Kumari worships the living goddess with a Tibetan bell in his left hand a Śaiva-shamanic damaru in his right. Original photo. Patan, 1997.

The identification and worship of a prepubescent girl, called kumārī, as living goddess has a long-standing history in South Asia. The Kathmandu

valley is home to a vibrant millennium-old tradition of royal kumārīs whose virginal bodies are believed to protect and empower the nation and its

citizens. Some of the myths, liturgies, and ideologies that inform contemporary interpretations of Nepal’s living goddess follow.

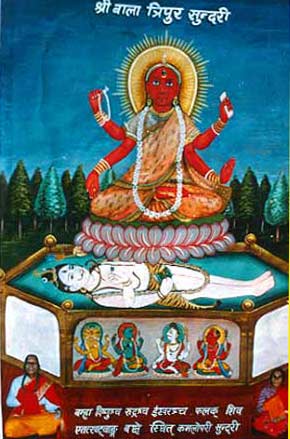

The goddess Tripurasundari in her form as the virginal child.

Private collection of author.

The word kumārī from Sanskrit means “young girl, virgin.” Throughout South Asia, evidence of Kumārī worship dates to the Ṛg Veda (circa 2000

B.C.E.) - in which prepubescent girls are venerated as incarnations (avatāra) of the divine feminine, called Devī or Śakti.

During the Hindu festival of Navarārtri or ‘Nine Nights’ it is still a common practice to select young girls to embody the goddess as kumārīs for

the course of the festival. There are also major centers of Kumārī practice at the Indian temples of Kāmākhya, Assam; Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu; Kanya Devi,

Punjab; and Karani Mata, Rajasthan; as well as several temples in the Kathmandu valley, Nepal. These traditions all share in common the understanding that

the ritual worship of select young virgin girls makes possible the descent of the divine feminine presence to earth.

Kumārī’s Divine Identities

The goddess most frequently identified with the Nepalese Kumārī is Taleju, whose name derives from the indigenous Newar language and translates

approximately as the ‘Goddess of the High Temple’. Taleju is commonly identified as the ‘fierce emanation of Durgā’, one of the most popular forms of the

great goddess.

Durgā and the Devīmahātmya

Mahā Devī, the great goddess, is unlimited in power. Durgā is venerated in homes and temples ranging from the southern tip of Kerala in India to the

Himalayas of Nepal. Her creation myth, recounted in the Devīmahātmya, emphasizes her as the embodiment of all powers.

Long ago, the gods were engaged in a battle with a terrible demon named Mahiṣa who received, though penance, the boon of invincibility from the creator

god, Brahmā. As a result, no single god could defeat him and Mahiṣa, driven by the hunger for power, was quickly becoming lord of all the three worlds.

Desperate, the lesser gods went to the highest heaven, called Vaikhuṇṭa, and sought the assistance of Viṣṇu and Śiva, the two mightiest of the Hindu gods.

Seeing that the situation was dire, these supreme leaders devised a brilliant military plan: create a ‘weapon’ that was the combination of the powers of

all the gods. This plan was actualized by means of all the gods generating their internal energy (tapas) and projecting it simultaneously into a

single field of power. From that combined field of power emerged the goddess Durgā, bearing the weapons of the gods in her multiple arms, three-eyed,

riding a tiger, and proclaiming herself to in fact not be a product of creation but rather the original source of creation.

Durgā proceeded to do battle with the invincible demon Mahiṣāsura. The demon assumed multiple forms in attempting to defeat the Goddess, but each time she

was victorious. Finally, he assumed the form of a buffalo (in Sanskrit mahiṣa means ‘buffalo’) but Durgā stunned him with the brilliance of light

emanating from her body and then beheaded him with her sword, forever earning the name Mahiṣāsuramārdinī, the Slayer of the Buffalo Demon.

As a slayer of invincible enemies, Durgā is identified not just as a goddess, but as the goddess, called Mahā Devī or ‘great goddess’.

Consequently, she is understood to be the source of and to contain all other goddesses within her.

The identification of the Nepalese royal Kumārīs with the Great Goddess, Mahā Devī, reveals a key facet of her identity and function as a living

divinity: she is the embodiment of a power (śakti) that protects the nation against any and all enemies of state.

To understand how a small virgin girl can embody such awesome power, we must take into account the ritual ideology and practice that undergirds the Kumārī

institution. It is ritual that transforms the young virginal girl into a divinity capable of destroying all enemies.

Vajradevī: The Kumārī as a Buddhist Wisdom Deity

The central power of the Kumārī institution is that it functions as a ritual mirror in which Nepal’s multiple ethnic groups see reflected their respective

cultural values. For Newar Buddhists, Kumārī is a living embodiment of the Vajrayāna Buddhist deity Varjayoginī, revered as Buddhahood or perfect

enlightenment, itself. As described in numerous Paddhatis and depicted in traditional Newar art, Vajrayoginī is naked, red skinned, dancing with ankle

bells, adorned with a garland of skulls, holding a skull bowl in her left hand and a crescent blade in her right.

To Buddhist initiates, Vajradevī is a wisdom ḍākinī, the female liberator who function is to assist those on the meditative path to awakening.

The male consort of Vajradevī is Cakrasaṃvara, ‘The Binder of the Wheel’. When represented as a united ‘father-mother’ deity (yab-yum)

Cakrasaṃvara and Vajradevī symbolize the fullness and completion of enlightenment. This identification of Kumāṛī with the female principle of liberation in

Buddhist Tantra indicates what initiates themselves see as the secret and highest purpose of the Kumārī institution: to manifest into the inherently

restrictive temporal realms of society the energy and wisdom of timeless transcendence.

Royal Patan Kumari during her daily worship as the supreme goddess. Original photo. Patan, 1997

Kumārī and the Ritual Technologies of Tantra

The technologies that transform virgin girls into divine Kumārī’s stem from Tantra, the Tantric system of ritual practice and related ideologies that date

back to the 4th century. Both ‘Hindu’ and ‘Buddhist’, assumes that all of existence is an unfolding of a singular conscious energy or śakti that manifests itself according to a precise geometrical and acoustic pattern termed maṇḍala, meaning ‘territory’.

The universe itself is the grandest of maṇḍalas, being the cosmic emanation of śakti. Within the cosmic maṇḍala, śakti replicates itself an infinite

number of times in a way akin to what modern physicists term fractals: self-replicating patterns in which the macro-form and micro-form are identical

(e.g., the smallest section of a coast line mirrors the form of the coast line itself). This ‘fractal logic’ is captured in the Tantric dictum ‘as in

the universe, so in the body’.

In other words, from the perspective of Tantric practitioners, called Tāntrikas, the body is a replica of the universe. If there is infinite power in the

universe - and Tāntrikas believe there is - then infinite power also resides within the body. The key, then, is to access and harness this power.

Girls designated to serve as Rāj Kumārīs are selected because their young, virginal bodies are deemed qualified to serve the nation as vessels for this

harnessing of divine power.

Priest performs yogic nyasa during the daily ritual of the living goddess, thereby sanctifying his inner being by linking it to the divinity present in the goddess before him. Original photo. Patan, 1997.

The first step in the ritual empowerment is the selection of a worthy candidate. The process is conducted by a committee of religious officials including

the Bāḍa Guruju or chief royal priest, the priest of Taleju and the royal astrologer. Additionally, the king (in times past) was invited to suggest

potential candidates. Candidates for the Rāj Kumārī are selected from the Newar Śākya caste (which claims links to the family of the historical Buddha) of

silver and goldsmiths. Candidates must be in excellent health, never have shed blood or been afflicted by any diseases, be without blemish and must not

have yet lost any teeth. Girls who pass these basic eligibility requirements are examined for the ‘thirty-two perfections’ which include a list of

apparently idealized female bodily attributes, such as ‘thighs like a deer’, ‘eyelashes like a cow’ as well as dark black hair and eyes and well formed,

complete teeth. However, recent Royal Kumārī, Rashmila Shakya, clarifies in her fascinating biography - a primary inspiration for this essay - that these

perfections are actually astrological references. It is the horoscope, far more than the physical body, which must be free of any indications of conflict

with the horoscope of the reigning king.

This emphasis on compatibility sheds light on the key function of the Kumārī: her function is to empower the king. It is for this reason that the tradition

claims the chosen candidate innately demonstrates the attributes ascribed to the great goddess in her various textual sources. Such attributes are said to

be particularly exemplified during the ten-day festival of Dashain, particularly on the Kālrātri, or ‘black night’, when 108 buffaloes and goats are

sacrificially offered to the Royal Kumārī as an emanation of the goddess Kālī. It is commonly believed that the young candidate is taken into the royal

Taleju temple and released into the courtyard, where the severed heads of the animals are illuminated by candlelight and masked men are dancing about. If

the candidate truly possesses the qualities of Taleju, she shows no fear during this experience. If she does show fear, then the next candidate is sought

and tested. As a final test, the living goddess must spend a night alone in a room among the heads of ritually slaughtered goats and buffaloes without

showing fear. Having passed all the tests, the child will stay in almost complete isolation at the temple, and will be allowed to return to her family only

at the onset of menstruation when a new goddess will be named to replace her.

Rashmila Shakya explains that the purpose of these particular rituals has less to do with whether or not the selected human candidate literally experience

no fear, but rather that they be represented in such a way. Whatever their own individual experience, the function of the ritual is to manifest a being who

is transcendent to fear.

Fulfillment of Wishes

The goddess Tripurasundari, a primary form of Kumai in Nepal, on the front of a wedding invitation from the late King Birendra, announcing the marriage of his daughter, Pricess Shruti. Author's private collection. 1997.

The technologies that transform virgin Nepalese girls into living conduits of these real unseen powers are described in sacred ritual texts called

Paddhatis. Paddhatis detail ritual prescriptions for daily worship, festival worship, and worship for specific intentions, such as the power to win an

election. Of these three types of ritual, the most common and most important is the daily ritual. Once the Kumārī is chosen, she must be ritually purified

each day so that she can be an unblemished vessel for Taleju. The heart of the ritual is the placement of the Kumārī on a ritual seat shaped in the form of

a maṇḍala while a Tantric priests worships her with special body postures (mudrās) and liturgical formulae (mantras) that

empower her body to be a living manifestation of what the Paddhatis call the Goddess of Universal Form (viśvarūpa-devī).

At the completion of each daily ritual, it understood that the power of the supreme goddess (parādevī) fully resides in the human form of the

Royal Kumārī and that therefore she deserves the official title of Taleju, identifying her as the king’s own sovereign deity. Affectionately, the Royal

Kumārī is commonly called by the members of her inner circle as Dyāḥ Meiju, Newar for ‘Mother Deity’.

As a Mother Deity it is believed that the Kumārī can transmit power or śakti directly into the bodies of those devotees who come to have her audience

(darśana).

For this reason, every day, after the daily ritual, the Royal Kumārī receives the faithful in her inner chambers for a brief period, providing an

opportunity for direct contact with living divinity. In other words, the ritual is the medium of transformation. Through ritual a human girl becomes the

microcosmic embodiment of the goddess. In this way, as Alexis Sanderson has noted, ritual makes the impossible possible.

The Kumārī is a medium through which the goddess Taleju disseminates her divine nature throughout Nepal, which the faithful perceive as her own body writ

large as geopolitical space. For the Tāntrika who has been initiated into the system of the maṇḍala, the entire country of Nepal is perceived as

the body of divinity. This is because Nepalese Tāntrikas operates according to a kind of inside-out logic that situates the origin-point of ‘objective’

space within the consciousness of the witnessing subject. In other words, from a Tantric perspective, the universe adapts itself to each individual’s

perception of reality. The Kumārī is for this reason called the ‘Wish Fulfilling Cow’ (kāmadhenu) for like that mythic being she too functions to

bestow the desires of the nation’s citizenry.

Worship of the hidden feet of the living goddess. Original photo. Patan, 1997

The Kumārī in History

According to the Nepalese dynastic chronicles, in 1192 C.E., King Lakṣmīkāmadeva first erected an image of Kumārī and established the Kumārī-pūjā, in

gratitude for the great wealth his family had accumulated. Over the centuries, subsequent inscriptions document Kumārī worship by the Nepalese kings.

Trailokya Malla, who reigned in the independent kingdom of Bhaktapur from 1562-1610, is credited with establishing the institution of the Kumārī in each of

the three Malla kingdoms. The accounts of this historical event are illuminating, as they highlight the institution’s links to mystico-erotic traditions of

Tantra, which view sexual union (maithuna) as an integral aspect of the Tantric path. Paralleling the classical mythology of Śiva and Pārvatī, we

are told that Trailokya and the goddess were playing dice. The king longed for intimate contact with his iṣṭa-devī, who consequently scolded him

and said that he could only communicate with her through a girl of low caste.

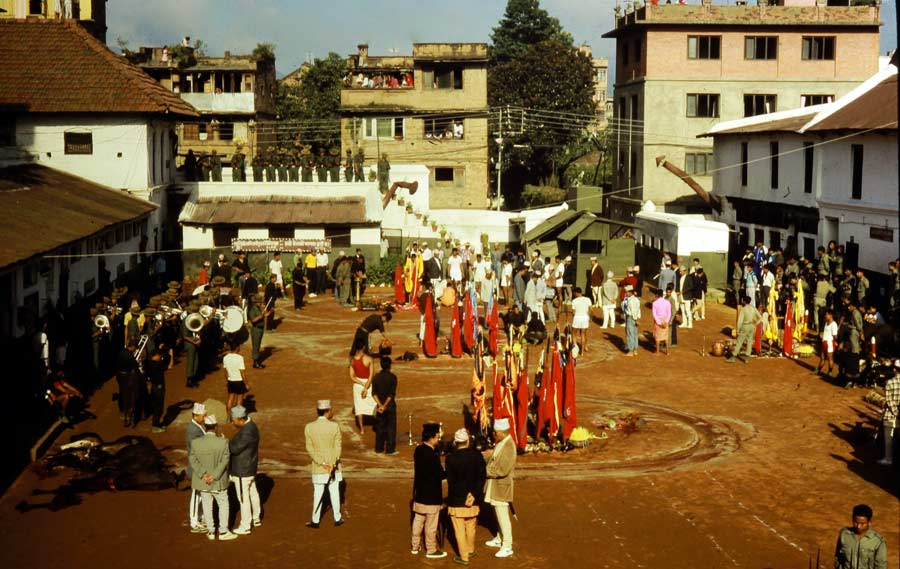

Perhaps the most significant historical example is King Pṛthivī Nārāyan Śāh (1723-1775). In historical accounts of his life, we find the intimate

relationship of Tantra to kingship and the role of the Kumārī. While king of Gorkha, a region in western Nepal, Pṛthivī Nārāyan arduously practiced the

Tantric yoga of Bālā Tripurasundarī, ‘The Beautiful Young Goddess of the Three Cities’. After he had practiced Tantric sādhana for twenty-five

years, this child goddess appeared to him and granted him the boon that he would conquer and unite the Kathmandu Valley. Pṛthivī Nārāyan and his troops

entered Kathmandu on the day of Indra Jātra, the occasion when the Kumārī bestows her divine approval upon the king. At the time of Pṛthivī Nārāyan’s

surprise attack, the then king of Kathmandu, Jaya Prakāś Malla, was preparing to receive the Kumārī’s blessing. Swiftly, and unexpectedly, Pṛthivī Nārāyan

rode into the royal courtyard and bowed before the Kumārī, who unhesitatingly blessed him. In that moment, popular legend goes, the king of Gorkha became

king of Nepal in a swift act of power that was the result of both political strategy and divine grace won through years of arduous devotion to the Goddess.

The Kumarī today

The most recent chapter in the history of the Royal Kumārī institution is one filled with tragedy and the demise of monarchy in Nepal. On June 1, 2001 King

Birendra Shah Dev and several members of his family were murdered at the Narayanhity Royal Palace in Kathmandu. While the official report is that the

king’s own son, Dipendra, shot his entire family before putting the gun to himself in a drugged state of rage, many Nepalese to this day believe that the

massacre was orchestrated by the king’s brother, Gyanendra, who came to power with the death of his brother and his entire family. According to Sthaneshwar

Timalsina, Professor at San Diego State University, there were signs that the Royal Kumārī did not favor King Gyanendra. When he came for her audience, it

is said that one of daggers in the inner sanctum of her residence fell inauspiciously to the floor, heralding, some believe, the demise of King Gyandendra

himself.

Sacrifice of 108 water buffalo to goddess Kumari on the occasion of the festival Dasein. Original photo. Durbar Square, Kathamandu. 1996.

The Benefits of a Living Goddess

With Gyanendra long since forced from office and the centuries-old institution of kingship officially extinct in Nepal, critics of traditional culture have

argued that there is no point in having a Royal Kumārī if royalty in Nepal is no longer a living tradition. However, important voices from with the

tradition have argued passionately for the wisdom of keeping Kumārī alive. Professor Deepak Shimkhada from Claremont College writes:

“By doing away with venerated, age-old customs, elements of the new Nepali government and some human rights organization may be going down the path to

wiping out their culture, history, and identity as Nepalis. Cultural identity is more important than political identity. As we move toward assuring

essential human rights for all, we should preserve those customs that make us who we are ... Judging by the situation on the globe all heads of states

could do with the blessings of a living goddess. The people of Nepal, who need and seek peace, harmony, and reconciliation, need Kumari’s blessings

more than ever.”

In this regard Dr. Shimkhada’s sentiments echo a long standing and deeply abiding belief that Nepal’s living goddess, as a Kumārī, embodies a wisdom and

power transcendent to the mortal frames that are her temporary embodied home. This transcendence is poetically captured by the fact that the recent deadly

earthquake in the Kathmandu valley, while leveling many structures adjacent to the home of the Royal Kumārī in Kathmandu’s historical Durbar Square, left

the Kūmārī’s home unscathed, as if nature herself were announcing, “This one shall not and cannot be harmed.” Although skeptics may view this incident as a

random example of how the damage from deadly quakes spares some structures while leveling others, to the faithful this is yet one more sign that Nepal’s

living goddess is still very much protected by powers beyond human comprehension.