Editor's Note: Audrey Truschke’s work concerns literary and historical interactions between members of the Sanskrit and Persian traditions in Mughal India.

Her current project investigates the literary, social, and political history of Sanskrit as it thrived in the Mughal courts from 1560 to 1650. In addition

to her research, she also maintains a website that seeks to promote online resources in

the study of early modern South Asia.

Audrey received her PhD from Columbia University in May 2012. During the 2012-2013 academic year, she was a research fellow in History and Asian &

Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge (Gonville and Caius College). She is a 2013-2016 Mellon postdoctoral fellow in Religious Studies at

Stanford.

-900.jpg)

Akbar at Ibadat Khana with Jesuits by Chester Beatty

Akbar at Ibadat Khana with Jesuits by Chester Beatty

Vikram Zutshi:

Please tell us about your academic specialty. What led you into this field initially and why did you decide to make it your profession?

Audrey Truschke:

I originally became interested in India through studying Sanskrit and the Indian epics, especially the Mahabharata, as an undergraduate. As a graduate

student I continued studying Sanskrit and also learned Persian. I decided to focus my doctoral work on Mughal India, especially interreligious relations

between Hindus, Jains, and Muslims. Today I work on cross-cultural exchanges, historical memory, and imperial power in early modern India.

Vikram Zutshi:

The entry and proliferation of Islam in India has always been a contentious issue. What do you hope to achieve with the thrust of your research? Were there

any surprises along the way?

Audrey Truschke:

As a historian, I strive to more accurately and fruitfully understand the Indo-Islamic past. I have no overarching agenda beyond this goal. Rather, I let

my research guide my conclusions, including times when those conclusions are at odds with certain modern political interests. I am frequently surprised by

what I uncover in my research. Perhaps the single greatest surprise to me and other scholars has been the depth and diversity of Mughal interest in

Sanskrit ideas and texts.

Vikram Zutshi:

How did Mughal rule in India evolve from it's early beginnings to the end? What were the major changes in governance and attitudes to the largely Hindu

subjects? What does your research tell you about religious conversion under the Mughals and coercive programs like the Jaziya tax?

Audrey Truschke:

Mughal rule was a long and bumpy ride. Babur, the first Mughal king, presided over a fledgling kingdom that his son, Humayun, lost control of entirely for

more than a decade. In contrast, under Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal ruler, the Mughal Empire was one of the geographically largest and most populous

polities of its day, encompassing well over 100 million subjects and stretching across most of the subcontinent. By the end of Mughal rule in the mid-19th

century, the Mughal sovereign was reduced to a pensioner who was eventually exiled by the British to Burma.

There are very few generalizations that one can responsibly make about the entirety of Mughal history, a period of more than 300 years. At times, Mughal

figures acted against the interests of select Hindu populations, such as by destroying specific temples. Overall, however, the Mughals were uninterested in

oppressing Hindus and rather strove to incorporate Hindu communities into the Mughal state and administration. Conversion to Islam was always welcome under

the Mughals, although it was not especially incentivized, and it was certainly not coerced on a large scale.

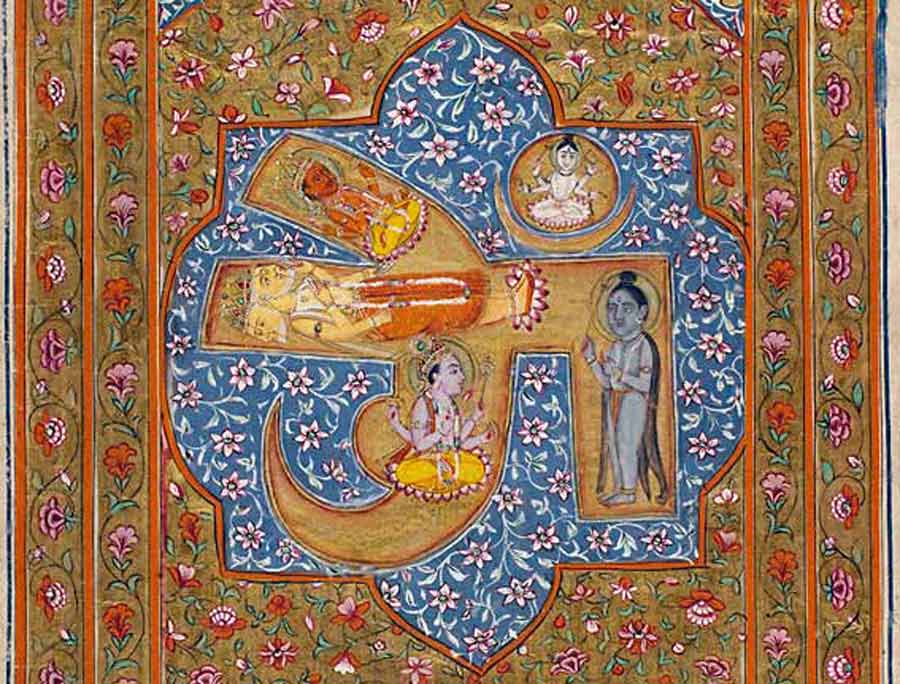

Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva within an OM in a Mahabharata manuscript from 1795

Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva within an OM in a Mahabharata manuscript from 1795

Vikram Zutshi:

Indian history is a highly disputed area. Many claim that Islamic atrocities were swept under the carpet by 'revisionist historians'. Is there a germ of

truth to these claims? Your findings on Aurangzeb in particular have raised some hackles. What are your conclusions on the subject?

Audrey Truschke:

I have no interest in vindicating or condemning the Mughals. Rather, like all serious historians, I seek to make better, more productive sense of the past.

Those who are interested in Mughal history primarily to identify Muslim villains object when I point out that there is no evidence for claims that

Aurangzeb tried to convert Hindus en masse or destroyed hundreds of temples. History often reveals inconvenient truths.

More controversial is my contention, which I stand by, that Aurangzeb has been misjudged and was not generally motivated by religious bigotry. Some

historians probably disagree with me on this point, at least in certain historical cases. The goal is for us to make that disagreement a productive

exchange of views that is motivated by the desire to truly understand the past, rather than to provide fodder for the communal politics of the present.

I am currently working on a book, titled Aurangzeb: The Man and The Myth, that will be published by Juggernaut in India in late 2016 that will

elaborate my views on Aurangzeb. View book at http://juggernaut.in/catalogue]

Vikram Zutshi:

What are your views on destruction of temples under Islamic rule? Are Hindus justified in feeling aggrieved at the wanton pillage and plunder of their

heritage over the ages? How does one acknowledge their claims without rubbing salt in historical wounds?

Audrey Truschke:

The destruction of temples under Indo-Islamic rule remains a seriously misunderstood topic today. Many people are under the impression that thousands of

temples were destroyed, whereas a few hundred is a far more likely number. People also have a tendency to talk about the demolition of Hindu temples and

forget that Jain institutions were also targeted. Perhaps most problematically, the political motivations that often fueled temple destruction are

frequently forgotten, and instead people assume, generally incorrectly, that religious hatred prompted such events.

Vikram Zutshi:

What are some examples of syncretic spirituality, art and culture that flourished under Mughal rule?

Audrey Truschke:

Early modern Indian society is filled with examples of cross-cultural exchanges on all levels. Much of my research to date has focused on the high Mughal

courts of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan where encounters between Hindus, Muslims, and Jains were an integrated part of court life.

Audrey Truschke:

Early modern Indian society is filled with examples of cross-cultural exchanges on all levels. Much of my research to date has focused on the high Mughal

courts of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan where encounters between Hindus, Muslims, and Jains were an integrated part of court life.

For example, Akbar sponsored the translation of the Sanskrit epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, into Persian. These translations were team efforts

that required a group of Mughal Muslim scholars working alongside a cadre of Brahmans. Nobody involved in the translations knew both Sanskrit and Persian.

Rather the Brahmans read the Sanskrit text and verbally translated it into Hindi, based on which the Mughal translators wrote down a Persian translation.

The lavishly illustrated manuscripts of these works number among the greatest manuscript treasures of India today.

Akbar and Jahangir also supported Jain intellectuals at court. These Jains were primarily monks from the Shvetambara tradition. They performed rituals on

behalf of the Mughal kings, including a Jain ceremony aimed at counteracting a curse on a daughter of Jahangir who was born under ill-fated stars. Jain

ascetics also taught Akbar how to recite the names of the sun in Sanskrit, and they convinced both Akbar and Jahangir to issue limited bans on animal

slaughter.

Shah Jahan sponsored some of the greatest Sanskrit thinkers of the seventeenth century, including Jagannatha Panditaraja and Kavindracarya Sarasvati. Both

of these luminaries are mentioned in Persian-language chronicles from Shah Jahan's reign. While they are most well-known today for their contributions to

Sanskrit intellectual culture, both were valued at the Mughal court as vernacular singers.

Alongside these elite exchanges, parallel cross-cultural activities also took place in more popular realms in Mughal India. For instance, Sufi and bhakti

saints often occupied a space that cut across Hindu and Muslim communities. Precolonial Indian history remains significantly understudied, and future

scholarship will continue to enrich our knowledge of this vibrant cultural period.

Vikram Zutshi:

Describe your forthcoming book, Culture of Encounters. What would you like readers to take away from your work?

Audrey Truschke:

Culture of Encounters

recovers the forgotten story of how the Persian-speaking, Islamic Mughal Empire supported classical Sanskrit literature and its associated Brahman and Jain

intellectuals. The book addresses the period from 1560 through 1660, during which the Mughals rose to prominence as one of the most powerful dynasties of

the early modern world. The predominant scholarly and popular narrative posits that the Mughals, as an Islamic polity, had little interest in traditional

Indian literature or knowledge systems. My book overthrows this erroneous, persistent presumption by detailing how members of the Mughal elite under Akbar

(r. 1556-1605), Jahangir (r. 1605-1627), and Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1658) supported and engaged with Sanskrit thinkers, ideas, and texts.

Audrey Truschke:

Culture of Encounters

recovers the forgotten story of how the Persian-speaking, Islamic Mughal Empire supported classical Sanskrit literature and its associated Brahman and Jain

intellectuals. The book addresses the period from 1560 through 1660, during which the Mughals rose to prominence as one of the most powerful dynasties of

the early modern world. The predominant scholarly and popular narrative posits that the Mughals, as an Islamic polity, had little interest in traditional

Indian literature or knowledge systems. My book overthrows this erroneous, persistent presumption by detailing how members of the Mughal elite under Akbar

(r. 1556-1605), Jahangir (r. 1605-1627), and Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1658) supported and engaged with Sanskrit thinkers, ideas, and texts.

This history of encounters with Sanskrit, I argue, dramatically undermines the prevailing view of the Mughals as an exclusively Persian-medium polity and

instead reveals a polyglot empire. I introduce cross-cultural relations with Hindu and Jain thinkers as a major way that the Mughals formulated what it

meant to be rulers of India. The narrative of Sanskrit at the Mughal court is also central to understanding the development of early modern Brahman and

Jain communities who often used selective memories of their Mughal connections to define themselves in politically salient ways.

Ultimately the book takes readers far beyond the Mughal court and provides the first detailed account of a shared cultural movement, defined by repeated

encounters across linguistic and religious lines, that altered the political and intellectual trajectories of early modern India. I hope that readers walk

away with a better understanding of Mughal history, precolonial Hindu-Muslim relations, and the possibilities that this past opens up for cross-cultural

relations today.