photo by Vikram Zutshi

Stories are the lifeblood of Kashmiri socio-cultural and political life. Every rivulet, spring, tree, mountain, meadow, shrine, village, king, personal

name, and of course more momentous events such as Kashmir’s origin, or its transition to Islam, have stories attached to them, often in multiple, competing

versions. In autumn, as the majestic Chinars take on a reddish-golden hue and there is a perceptible chill in the air, stories mingle with people as they

congregate around the harvest, and caretakers and pirs from shrines wander the countryside collecting rice, lentils, and apples in exchange for a

variety of tales about the mystics and kings of yore. The stories are then retold by the elderly men and women of households as children gather around

blankets and kangris on frigid winter nights. Anyone who grew up in Kashmir or with Kashmiri grandparents remembers these stories with deep

nostalgia. My own paternal grandfather in particular told many a story about the gambols of the devs and other holy beings in the springs,

mountains, and meadows of the beautiful Valley, thus transforming it into a sacred landscape.

Hatim Tilawon, Storyteller

European orientalists who devoted years to researching and collating Kashmir’s Sanskrit texts at the turn of the twentieth century were amazed to discover

a vibrant tradition of storytelling in the vernacular Kashmiri that paralleled Kashmir’s rich, multilingual textual traditions. The orientalist Aurel Stein

and the linguist George Grierson went so far as to spend weeks with a professional storyteller, Hatim Tilowon (pictured right), recording his stories,

translating them into English, and later publishing them in a collection entitled Hatim’s Tales. Stein and Grierson continually expressed their

surprise at the sheer number of stories Hatim could recite, and the range of topics that they covered, including vivid descriptions of village life, the

love story of Yusuf Zuleikha, the adventures of Mahmud of Ghazni with a fisherman, and the turmoil created in Kashmir as a result of Sir Douglas Forsyth’s

mission to Yarkhand in 1873-4.

While researching Kashmir’s historical tradition, I realized that storytellers and the stories they told served a significant purpose by connecting

Kashmiris to their own past and the history of their land. And today, in a society ravaged by conflict, stories are the only way for people to hold on to

memories of a past that no longer exists and may never return. Thus, when I heard about the possibility of meeting a professional Kashmiri storyteller on

one of my research visits to Kashmir, I pounced on the opportunity. Muhammad Ismail Mir, an octogenarian who had spent the better part of his life

narrating tales of various kinds for a living, resided in Mujgond, a village 30 kilometers from Srinagar. We had no trouble locating his modest dwelling

because everyone in the village knew the storyteller and pointed us in the direction of his home. The red-gold leaves from the Chinars surrounding the

house carpeted the path leading up to the door, where a sprightly Mir stood waiting to welcome us. It was a crisp October day, and a perfect time for

storytelling.

Over steaming cups of salty Kashmiri tea, Mir began by telling us the story about his own origin as a storyteller. As with most origin stories from

Kashmir, this too had a divine foundation. When Mir was a child, he was visited in a dream by a holy man, who asked him to tell stories. Mir protested,

saying that he was illiterate and did not know any stories that he could tell. The holy man asked him to try, and as soon as he opened his mouth to protest

yet again, stories poured forth from him. When Mir woke up, he could recall not just the dream, but also the stories. Through the course of his life, the

unlettered Mir has painstakingly collected and committed an impressive number of stories to memory. Some were taught to him by his father-in-law, others he

gathered from listening to recitations of books by professional book-readers at people’s homes, and still others were read out to him by his own children,

and more recently, his grandchildren. Since he sings the stories rather than simply narrating them, Mir performs a story only once it has been transformed

into Kashmiri verse. His most popular narrations are versified Kashmiri tales such as Himal Nagaray, Bomber Yamberzal, and Akhnandun.

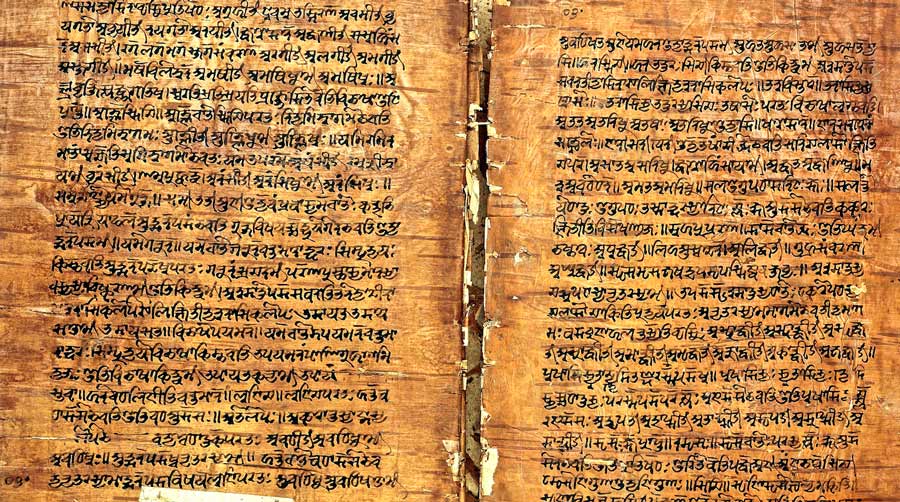

Birch bark manuscript from Kashmir of the Rupavatra Wellcome

Storytellers like him, thus, form an important bridge

not just between the textual and the oral,

but also between genres and languages.

Tuning the Rabaab for the performance of Himal Nagaray

Accompanied by his sons on the rabaab (string instrument), tumbakhnari (earthen pot), and harmonium, Mir performed for us the classic

Kashmiri story, Himal Nagaray. As soon as the performance began, men, women, and children appeared out of nowhere and crowded around the small

room, in the doorways, even by the windows, listening with rapt attention to this familiar tale. There was raucous laughter and cheers as Mir sang about

the haughty and shrewish wife of the poor Pandit, who leaves home to escape her taunts, and returns with a sack to present to his wife in which he has

placed a snake. The snake takes the shape of the beautiful boy, Nagaray, who falls in love with the princess Himal. Mir’s singing led us through the

vicissitudes of their love, ending in their death, and ultimately, in this particular version, with their resurrection.

The storytelling medium is necessarily open-ended and offers the possibility of multiple outcomes depending on the context. It does not elide conflict and

difference; instead, it provides a forum where they can be discussed and negotiated. Like many Kashmiri stories, Himal Nagaray is powerful

precisely because it crosses so many boundaries, such as of class and religious affiliation, and between life and death, nature and humanity, and the

sacred and the temporal. It thus allows listeners to envision Kashmir as a land where such traversals, and the resultant coexistence, were - and might

still be - possible.

Shikara in Dal Lake in Kashmir

This in part explains why the culture of storytelling came under attack in the wake of the insurgency. Mir shuddered as he described the days when he could

no longer perform for fear of being assaulted. And the violence to stories and storytellers is not just physical; Kashmiri traditions such as Bhand Pether (street theater) and Ladishah (minstrels) continue to be criticized for promoting myths and superstitions among the gullible

masses, as a class of intellectuals, particularly in the media, calls for a more factual understanding of Kashmir’s history and politics. Mir dismisses

this claim, and is now at the forefront of reviving the storytelling tradition and teaching it to others so that it can survive for future generations of

Kashmiris.

Motilal Kemmu, a Kashmiri playwright who has been deeply involved with the Bhand Pether tradition,and has directed several theatrical versions of Himal Nagaray, similarly believes that it is only by recounting stories which have been doing the rounds in Kashmir for centuries that Kashmiris

can continue to memorialize a past that is fast slipping away. If not, the stories of cooperation, conciliation, and alliances across religious and

political divides are in danger of being forever erased by stories of conflict, violence, and discord. After all, the springs where Himal and Nagaray met

and were reunited in the story, and which were visited by Kashmiris to commemorate this legend until the area was taken over as an army camp, have almost

dried up.

Stories have been a powerful means of communication in Kashmir for a reason. They have allowed the largely unlettered common people to participate in

defining their land, and negotiate to the extent that it is possible, their own place within it. It is not surprising that boundaries are often resisted

and navigated in these stories as the poor and oppressed take on the rich and powerful, and as humans challenge death itself, because the stories are part

of a larger narrative tradition that asserted Kashmir’s right to define itself within the framework of much mightier empires. Deeply embedded in Kashmir’s

landscape and displaying a powerful geographical sense, these stories, and the tradition of which they are a part, inhibit the past from being overtaken by

the present, and prevent Kashmir from forgetting itself.

This article originally appeared on KashmirConnected