To have a serious discussion about ancient Indian astrology we have to understand time. The zodiac is called the Kālapuruṣa in Sanskrit, or the

personification of Time (Kāla). All things move through the power of

Time, known as Kāla-śakti or Kālī.

The nature of reality is pulsing. Life is breathing; the heart is beating; the day and night are turning out our experience.

Pulsation requires the interplay of two forces. Śiva and Śākti, the Mother and Father, the Sun and Moon, create the pulsation which is

the basis of all manifest existence. The Chinese call this force of opposites the Yin–Yang. In Sanskrit, it is called the Yugamaka – the couple, the pair, or the

polarities. The Sun and Moon are the visible representatives of this Yugamaka, and they create time that pushes all things forward – the trees to bud, the

flowers to bloom, and the bees to pollinate.

Through the movement of the Sun and Moon, all time cycles come into existence. The western Gregorian calendar, set in place by the pope of the Catholic Church, is not based on natural time. The Vedic calendar, used throughout

millennia in India, is the mapping of the visible heavenly movements that are observed with astronomy. The Vedic calendar is a pulsating dance of the two

divine luminaries that create a luni-solar calendar.

|

Day

|

dina,vāra, ahorātra, vāsara

|

|

Month

|

māsa, ahargaṇa

|

|

Year

|

varṣa, ṛtuvṛtti,[1] saṁvatsara, abda, śarada[2]

|

The three basic astronomical cycles are the day (based on the rotation of the Earth on its axis – seen as the movement of the Sun); the month (based on the revolution of the Moon around the Earth – creating phases relative to the Sun); and the year (based

on the movement of the Earth around the Sun – seen as the Sun’s change in position in the sky and against the stars). As the Sun rises and sets, it creates

the days; and the Moon waxes and wanes, creating the months. The Earth–Sun cycle creates the year, which is divided into twelve lunations by the

Moon. In these cycles are harmonics – numerical songs that create a matrix in which consciousness takes embodiment.

It would seem easy to calculate a calendar, but complexity arises because the year is not made of an integral number of days or an integral number of

months. The harmonic is deeper, richer, and more complex. Different cultures have used very different calendars and ways of rectifying this. Even in India,

throughout the millennia there have been various systems utilized, and various places to start within a cycle.

To begin understanding the basics of Vedic timekeeping we must understand the calculation of lunar months and solar years, which have within them solar

months and lunar years. The solar months are considered the hinges, on which the doors of the lunar months move. What is a door without

hinges, or hinges without a door? The Sun and Moon work together to create a luni-solar calendar that integrates the male and female, Śiva and Śakti, prakāśa and viśrama, or the pumping and resting of the heartbeat.

The lunar cycle divides the year into twelve harmonics. The year then resonates to this harmonic of twelve, and divides itself into twelve solar months.

Like dancers, they move together. Time and its units are not man-made – they are man-observed. The divisions of time are divine harmonics that were

recognized by the ancients.

Synodic Month (Lunation)

The Sun gains 1 degree per day, while the Moon gains 13 degrees per day; they are both moving. The more rapidly moving Moon is chasing the slower and more

steadily moving Sun. The synodic month is the period in which the Moon gains one complete revolution over the apparent or visible motion of the Sun; or 360

degrees over the Sun (not just moving 360 degrees in the zodiac). When the Sun and Moon have the same longitude, they enter union (saṁgata), known

as syzygy, or the New Moon conjunction.[3]

The time from one New Moon conjunction to the next conjunction is approximately 29.5 days; according to Sūrya Siddhānta it is 29.530587946 days.

The modern calculation is 29.530588853 days, which is the same for the first six decimal places, though it is getting longer by a little less than a

fiftieth of a second per century.[4]

The mean New Moon conjunction occurs every 29.530587946 days (29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes, 3 seconds) but the actual New Moon does not recur at exactly

this interval. The mean motion is the average motion, which is a constant; while the actual or true motion is what is actually happening, and has

fluctuations. [5] The Moon may be fast or slow according to its elliptical motion at the time of becoming

new, and this anomaly needs to be taken into consideration. [6]

The moment of the New Moon conjunction marks the beginning of the lunar month and the end of the previous month. This calculation is called amānta

months (which is used in most places in India today).[7] The Ṛgveda talks about the Sun and Moon cycles, and

says that the Moon, as she invigorates (pyāyana) herself after having been drunk (prapiba) by the gods, gives shape (ākṛti) to

the months (māsa).[8] The Moon wanes, having had her light drunk by the gods; and then after the New

Moon conjunction, which starts a new lunar month, grows in light and strength again.

Solar Year

The solar year is based upon the Sun’s 365-day motion through the zodiac as perceived from Earth. There are two types of solar year: the tropical year and

the sidereal year. It is this difference between these two types of year that creates a variation between the stars and the seasons. [9]

The tropical year is the period of time from one vernal equinox to the next which, according to modern calculations, is 365.2422408 days; though the

tropical year is getting shorter by a half-second every century[10]. The utility of the tropical solar year

is for starting the seasons at the same time every year. The Gregorian calendar is presently based upon the Sun’s motion only, and therefore utilizes the

tropical year.

The sidereal year is the period of time wherein the Sun passes through all twelve signs of the zodiac and returns to zero degrees at Aries ( Meṣa saṅkrānti). The length of the solar year according to the Sūrya Siddhānta is 365.258756484 days; modern data lists it as

365.256363051 days. The anomalistic solar year is a third calculation that takes into account the difference in speed of the Sun at different times of the

year when the Sun is farthest from and nearest to the earth. This varying pace is needed for calculation of the exact point of the New Moon conjunction,

and the precise time of sunrise. The Vedic calendar utilizes the sidereal solar year (with the correction for the Sun’s anomaly), as it is based upon the

location of the luminaries during the New Moon conjunction and at sunrise.[11]

A calendar is more than merely a device for the numbering of days. All calendars are directly bound to the ever-recurring cycles of nature, most

commonly manifested in the rotation of the earth and its cosmic influences; their underlying purpose is to help man adjust to these cycles and the

forces that permeate them by achieving rhythmic flow of natural events. Ultimately this brings a sense of harmony with the Universe.

-José A. Argüelles[12]

photo by Stephen F. Corfidi

Interaction of Solar and Lunar Months

Saṅkrānti

is the time when the Sun enters a new sign and is within its zero-degree placement there.[13] As the

sidereal solar year begins with Meṣa saṅkrānti (entry into Aries), this is also the first solar month. A solar month is based upon the motion of

the Sun through each of its signs, and is related to the energy of the Sun.[14] The second month begins

with 0° of Taurus (Vṛṣabha saṅkrānti). As the Sun’s velocity varies, a solar month will have either 29, 30 or 31 days.

|

Saṅkrānti[15]

|

Approximation[16]

|

Lunar

Month

|

Rudra[17]

(Śaiva)

|

Viṣṇu

(Vaiṣṇava)

|

|

Mīna

|

March–April

|

Caitra

|

Bhīma

|

Vaikuṇṭha

|

|

Meṣa

|

April–May

|

Vaiśākha

|

Manmatha

|

Janārdana

|

|

Vṛṣabha

|

May–June

|

Jyeṣṭha

|

Sakuni

|

Upendra

|

|

Mithuna

|

June–July

|

Āśāḍha

|

Sumati

|

Yajñapuruṣa

|

|

Karka

|

July–August

|

Śrāvaṇa

|

Nanda

|

Vāsudeva

|

|

Siṁha

|

August–Sep

|

Bhādrapada

|

Gopālaka

|

Trivikrama

|

|

Kanyā

|

Sep–Oct

|

Āśvina

|

Pitāmaha

|

Yogīśa

|

|

Tulā

|

Oct–Nov

|

Kārttika

|

Dakṣa

|

Puṇḍarīkākṣa

|

|

Vṛṣcika

|

Nov–Dec

|

Mārgaśirṣa

|

Caṇḍa

|

Kṛṣṇa

|

|

Dhanus

|

Dec–Jan

|

Pauṣa

|

Hara

|

Ānanta

|

|

Makara

|

Jan–Feb

|

Māgha

|

Śauṇḍin

|

Achyuta

|

|

Kumbha

|

Feb–March

|

Phalguna

|

Pramatha

|

Cakradhāri

|

The solar months are considered the hinges, and the synodic lunar months the doors, of the Vedic calendar. The lunar month has its name

determined by a New Moon conjunction occurring relative to a particular saṅkrānti. Vedic and Hindu rituals, festivals and vratas are determined according

to the lunar month (the door); but that door is determined based upon the solar month (the hinge that opens the door).

The lunar month is named according to the solar month in which it has its New Moon conjunction.[18]

Presently, in India, it is the sidereal solar year beginning with Aries that determines the entire lunar year. In the ancient calendar text, Vedāṅga Jyotiṣam,[19] the mutual relation of solar and lunar months is kept from tropical

Saṅkrāntis, starting at the winter solstice.[20]

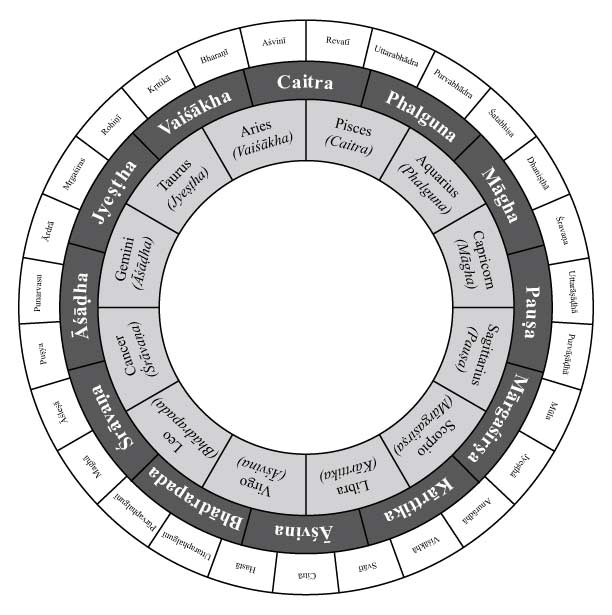

Figure 1: Innermost circle is the solar months.

Middle circle is lunar month named according to the New Moon conjunction.

Here the lunar month starts in the middle, but it may start anywhere within the sign.

When a standard All-India calendar was being created in 1952–7, the Calendar Reform Committee recommended that the luni–solar months be linked to the

tropical months. This suggestion was not followed, since the calendar had been linked to the sidereal months for approximately one millennium. The Indian

government instead created a tropical solar calendar with months named after the classical sidereal nakṣatra months, which was not accepted by

most Indians. The committee named as the “Review of Committee on Indian Calendar and Positional Astronomy” met in 1986 to make new recommendations, which

were not followed. Finally, new recommendations in 2004 were accepted to make the solar months coincide with the sidereal zodiac signs.

The luni–solar calendar is a type of cosmic attunement that connects us to an organic time. It is the interaction of the solar year with the lunar cycles

that determines intercalary months, which allows the lunar months to align with the seasons. This is a dance between the Sun and Moon, as well as between

fire and water.[21] This dance is the balance we aim to achieve in ourselves between the male

and female polarities.

Broken Hinges and Missing Doors

In general, New Moon conjunctions and Saṅkrāntis occur alternately; and therefore each door has its own hinge. [22] There may occasionally be a shorter lunation that does not have a Saṅkrānti. This makes two New Moon

conjunctions within one solar month.[23] This additional lunation becomes the intercalated lunar month

called an Adhika māsa. In this case both lunar months will take the same name. The first month is Adhika (additional, abundant,

intercalated); and the second month is Nija (innate, native). For example, there could be an adhika Śrāvaṇa māsa and a nija Śrāvaṇa māsa. Most

traditions utilize the natural (nija) month for standard festivals. Adhika months ordinarily occur once every three years.

Rarely, there is a longer lunar month that has two Saṅkrānti. When this happens a lunar month is suppressed, as there is no hinge for the door to turn on.

This suppressed month is called a lost month (kṣaya māsa).[24] The Kṣaya month is

very rare, while the intercalary month happens about once every three years. These variations are the key for keeping the solar and lunar cycles in

harmony, and thereby allowing a functional luni–solar calendar.

The intercalary month was utilized from ancient Vedic times.[25] The Ṛgveda says the Sun and Moon move

proceeding and following each other, because of Māyā, like two children playing round the sacrifice.[26]

Time is seen according to the Sun’s movement because it is steady and constant each year; it beholds all existence (viśvānyanyo bhuvanābhicaṣṭa);

while the lunar months move all over the place like the emotions constantly fluctuating, yet they create the moment (ṛtūṁranyo vidadhajjāyate).

The Vedic calendar keeps stability with the Sun, like the ātman keeps an individual centered. The individual happenings are guided by the Moon, like the

emotions fluctuating across the mind.

The results of being born in the different lunar months are listed in Janardan Harji’s Mānsagarī. Someone born in the month of Caitra is

likely to be happy, perform good works, be egotistical, have bloodshot eyes, deal with anger, and have a changeable love life. Someone born in the lunar

month of Vaiśākha is likely to be a pleasure-seeker (bhogī), wealthy, of good disposition (su-citta), playful, handsome, and a

favorite of the opposite sex. Those born in the month of Jyeṣṭha will enjoy going abroad, will have a good mind (subhacitta), be wealthy

and long-lived, and have good intelligence. Birth in the month of Āśāḍha gives sons and grandsons; Śrāvaṇa gives equanimity in good or

bad times; while Bhādrapada makes one soft-spoken but talkative, and always delightful. Āśvina has good qualities; is happy, poetic,

wealthy and desirous. Those born in the month of Kārttika are harsher with tough personalities, and are often involved in trade. Mārgaśirṣa will have lots of friends, be soft-spoken, and helpful to others. Those born in the lunar month of Pauṣa are said to be

intense and brave. Māgha birth indicates good intelligence, bravery and harsh speech; while Phalguna birth indicates a fair complexion,

good wealth, education and comforts, as well as vacationing to foreign places. Birth in an Adhika māsa is said to make one spiritual, virtuous,

and unconcerned with worldly matters; while birth on a Kṣaya māsa is said to make one ignorant, poor and diseased.

Intercalary Month (Adhika Māsa)

The intercalation is how the lunations (Moon) are wedded to the year (Sun); and it is this wedding that keeps the lunations in tune with the seasons. To

understand the mathematical harmonics more deeply, we shall calculate the first six years of Kali Yuga to see the actual functioning of the intercalary

month.[27]

At the end of the first sidereal year and beginning of the second, 12 synodic months had passed, and 10.891701134 days of the next lunation. [28] At the end of the second year, 12 synodic months had passed, and 21.783402268 days of the next

lunation. By the next year there were 12 lunations plus 32.6751034 days. This is actually 32.6751034 days; so we subtract a lunation of 29.530587946 days,

which is therefore 13 lunations and 3.144515454 days of the next lunation.

|

Kali Yuga

|

B.C.E.

|

First New Moon in That Year

|

Synodic Months in That Year

|

|

0

|

3102

|

Absolute beginning of the year

|

12 lunations and 10.891701134 days[29]

|

|

1

|

3103

|

18.638886812 days into the year

|

12 lunations and 21.783402266 days

|

|

2

|

3104

|

7.74719 days into the year

|

13

lunations

and 3.144515454 days

|

|

3

|

3105

|

26.386072492 days into the year

|

12 lunations and 14.036216586 days

|

|

4

|

3106

|

15.49437136 days into the year

|

12 lunations and 24.927917722 days

|

|

5

|

3107

|

4.60335 days into the year

|

13 lunations

and 6.28903091 days

|

Again we can see that since there were 10.891701134 days of the next lunation in the previous solar year, the next lunation starts 18.638886812 days into

the year (not 29.530587946 days, as in the previous year, which began on the New Moon). Each year the New Moon conjunction will start 18.638886812 days

later. At the end of the second year we have 18.638886812 days multiplied by 2, which is 37.277773624 days. This amount of time is more than one lunation,

and therefore we subtract 29.530587946, and have 13 lunations, with the next New Moon conjunction happening 7.747185678 days into the month.

Conclusion

There are many variations throughout India based on the region/kingdom and time period. What is more important for the practitioner than the details of

each calculation are the general concepts of the Sun and Moon creating a system of time together. There are 12 solar signs based on 12 lunations. The Full

Moon names the solar signs. The lunar month is named by the solar sign containing the New Moon conjunction. This interaction makes a luni–solar calendar.

The dynamics of the calendar are fundamental to how we look at time and how we calculate it. The Vedic calendar comes from watching the cycles of the Sun

and Moon, and then expressing the natural cycles in these observations. The stars turning in the year and the lunations are already present; the human mind

is just watching them and giving them names. We watch the dance of the Sun and the Moon, and see how all the festivals and times of worship are guided by

this clock. And when we look deeper, we see that this dance is a movement of consciousness, in the sky above and in our personal experience.