Editor's Note: Dr. Miller has translated several classical Indian texts from Sanskrit into English. This is the third part of Richard's translation of Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, along with his rich insights and incisive commentary.

Read Previous Chapters

I. 12-16

Practice, Non-Reaction, and Colorlessness

Following up on sutras 5-11, Patañjali now presents us with five sutras that define right effort, action or practice (abhyāsa) that enables us to go

beyond confusion, doubt and misidentification with the movements of the mind (prakṛti) that otherwise distract us from recognizing and awakening to our

Essential Nature (puruṣa), which is always present.

How does one attain right understanding of these five mental states?

I. 12. abhyāsavairāgyabhyā - tannirodhaḥ

abhyāsa: persistent action (practice) that comes about through right understanding

vairāgyābhyam:

colorlessness; non-reaction; without attachment, aversion or feigned neutrality

tan: those (five vṛttis)

nirodhaḥ: stilling; stillness

Right understanding of the five mental states comes about through right approach and non-attachment to the distracting

influences of attractions, aversions or feigned neutralities that otherwise bind attention and give rise to confusion and the mistaken identity

that one’s unchanging essential nature is actual part of the changing movements of the mind.

Sutras 12-16 define right effort, action and practice (abhyāsa) and its impact on awakening to our essential unchanging nature (puruṣa). Right action

has three wings: devotion (satkara), mindfulness (samādhi) and wisdom (viveka khyati). By right exertion of these three, spontaneous welcoming and

detachment arise and we learn how to transcend the confusion and binding changing movements of the mind, and recognize and abide as our essential

unchanging nature.

The river of the mind can flow in one of two directions: 1) towards the changing sense objects and mental states of nature (prakṛti), or towards

unchanging essential nature (puruṣa). Discriminative understanding (viveka) and sustained practice give rise to the ability to recognize essential

nature (puruṣa) as always uncolored (vairāgyābhyam) by the changing mental states (prakṛti), even as changing mental states

continue to arise.

Yogi wearing a mala and using a meditation strap

(‘yogapatta’) around his torso and knees

to allow him to maintain his posture.

Granite sculpture, cca. 18th century, origin Madras, India

In the face of difficulties as doubt, confusion and misidentification, how should one proceed?

I. 13. tatra sthitau - yatno 'bhyāsaḥ

tatra: there; in the light of puruṣa; unchanging essential nature

stithau: being firmly established; steady; tranquil

yatno: with concentrated mental effort; steady adherence; steadfast endeavor

abhyāsaḥ: is called practice; right exertion; right approach; right action

One should not be deterred on account of the difficulties encountered along the way, but should always proceed slowly and steadfastly

. Steady, continuous, persistent, and steadfast endeavor to stand firm in the understanding of being one’s true and underlying unchanging essential nature is known as right practice and right exertion.

Patañjali refers to any repeated attempt to attain steadiness (stithau) as right effort, action or practice (abhyāsa), which is always attained through

trial and error. One should always endeavor to stabilize attention so that it becomes like a river that flows in one direction, towards your Essential

and unchanging Nature, rather than to the changing objects that arise in the mind that otherwise bind attention. This requires patience, love,

fortitude, zeal, and determination (virya).

“Spirit is realized not by one who has no energy, nor by one who is subject to delusion, nor by knowledge devoid of non-attachment. When the wise

person exerts him/herself with energy, knowledge, and renunciation, his/her soul reaches the abode of Essential Nature.” —Mundaka Upanisad

One much keep in mind that practice should never become mechanical (YS II.27) or merely intellectual (YS IV.4). Right practice entails coming to the

seamless heartfelt understanding of being Essential Nature (puruṣa) across all endeavors and states of mind, body and worldly life that one encounters

throughout one’s lifetime.

Painting, Shivite yogi meditating, gouache on mica,

Varanasi, second quarter of 19th century

When is practice firmly grounded?

I. 14. sa - tu - dīrghakāla - nairantarya satkāra - āsevito - dṛḍhabhumiḥ

sa tu: that; but

dīrgha kāla: long; time

nairantarya: constantly and continuously; without interruption

satkāra: reverent devotion; with earnest attention; sincerity; skillfully in the right manner

āsevito: pursued; continued; followed; attended to

dṛdha bhumiḥ: firmly grounded and established

One is

firmly grounded in practice when one stands firm and undistracted in the truth of being Essential Nature without interruption, for a long time, with total devotion, sincerity, and earnestness.

Practice is deeply rooted and bound to succeed when it is continued for a long time, without interruption, with heartfelt devotion, and when the

results, good or bad, do not bring about distraction, elation, dejection, or feigned neutrality. Practice should be a 365 day, 24 hours, 60 minutes an

hour, 60 seconds a minute affair. Practice is firmly grounded through five principles;

1. Tapas: Our willingness to suspend comfort

2. Śraddha: Steadfast faith that we are traversing the right path

3. Vidya: Unwavering trust in the approach that we are involved in

4. Satkara: Ardent and steady devotion to truth and standing firm as Essential Nature

5. Brahmacharya: Our ability to stand firm as our Essential Nature with every step we take, whatever our circumstances

How does one avoid distracting influences without being distracted by such effort?

I. 15. dṛṣtānuśravika - viṣayavitṛṣṇasya - vaśikārasaṁjñā - vairāgyaṁ

dṛṣtā: seen; visible; perceptible by the senses

anusravika: revealed or heard about from scriptures or sages

viṣaya: material objects of mind and senses

vitṛṣṇasya: thirstlessness for material objects; non-clinging; non-craving

vaśikārā: mastery over; controlled; established

saṁjñā: comprehension; full knowledge

vairāgyam: colorless; detachment; non-reaction; dispassion

When the mind’s compulsive and over-powering craving for objects seen, heard or perceived is skillfully, turned upon itself without

either suppression, repression, expression or indulgence, there arises intense and consuming passion in quest of the who, what, where, when and how

of craving itself, which is known as dispassion or uncoloredness.

Sutras 15-16 define dispassion, or what is otherwise know as colorlessness (vairāgya). Dispassion arises spontaneously and effortlessly when we see

through and are completely finished with something, whether it’s a thought, emotion or object such as a piece of clothing. At this point the mind’s

fancy with an object has lost all coloring and is no longer bound to the object through attachment, aversion, doubt, confusion, or misunderstanding.

When we play long enough in the field of objectivity, we realize ultimately that objects bring no lasting satisfaction. This can lead either to

despair, or to what I call, “The Great Turn of Attention,” where attention is turned away from objects and into the nature of craving itself and the

source of attention.

With right practice there arises right understanding of the constantly changing nature of all objects, seen, heard or perceived in any manner, which do

not ultimately provide lasting pleasure. These pleasures can be of a sensual nature, or those brought about through the practice of yoga itself

(siddhis).

At this level of practice, anything that disturbs the ability of attention to remain undistracted and directed towards inquiry into Essential Nature

now becomes uninteresting and unimportant. Only that which aids inquiry is deemed important. The movement of inquiry becomes all-consuming. Anything

that disturbs the ability of the mind to remain undistracted and directed towards inquiry is inherently uninteresting and unimportant.

1. At the start of an endeavor we attempt not to indulge in sense pleasures (yatamāna)

2. Taking a realistic inventory of our journey, attachment to some objects disappears, becomes weak to others, as a feeling of renunciation begins to

appear (vyatireka)

3. Although some curiosity remains, given the opportunity the mind does not indulge, and only the tendency for attachment remains (ekendriya)

4. The mind remains naturally dispassionate and no desires arise in the mind; (vasikāra vairagya)

Yacchedváuṋmanasi prajiṋastadyacchejjiṋána átmani;

Jiṋánamátmani mahati niyacchettadyacchecchánta átmani.

The wise first unite their sense organs (indriyas) into consciousness (citta), then consciousness into the feeling of “I am” (aham), then the feeling of “I

am” into Being (mahat), then Being into Awareness (jiivátmá), and finally Awareness into the Mystery that lies beyond, Essential Nature that is beyond all

sense of self, other and self-awareness.

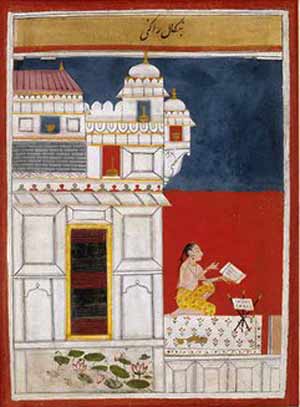

Painting, bangali ragini, lady dressed as yogi,

opaque watercolour on paper, Malwa, ca. 1660-1670

What is the correct approach in the quest to know oneself as unchanging Essential Nature?

I. 16. tatparaṁ - puruṣakhyāteḥ - guṇavaitṛṣṇyaṁ

tat paraṁ: the highest or ultimate colorlessness or dispassion (vairāgya)

puruṣa khyāteḥ: through discrimination of Essential Nature (puruṣa) from the world of changing objects (prakṛti)

guṇa vaitṛṣṇyaṁ: freedom and victory from craving of the changing forces of the body, mind and world (guñas)

In the beginning stages of practice turning craving or attention back upon itself may be based on 1) suppression or repression, or 2) actions with a

reward in view, or 3) faith to an accepted text, teaching or authority. But true self-inquiry transcends all qualified acts of self-discipline, when Essential Nature that is beyond the conditioned mind is directly seen to be free of all craving.

In sutra 16 Patañjali's introduces the concepts of puruṣa and the guṇas, which are based on his understanding of Saṁkhya, which is the philosophical

orientation that informs Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras. In this sutra Patañjali is addressing the understanding that when we truly understand our Essential

Nature we will no longer be disturbed by the changing circumstances of either our mind, or the world around us. He is emphatically stating that realization

of Essential Nature leads to the highest state of colorlessness and dispassion (vairāgya), wherein our clarity of understanding, vision and action is

effortless and natural (sahaj samādhi). Here, we always know how to act correctly in every situation, no matter our circumstance.

For Patañjali yoga entails going beyond all attachments and aversions to changing objects so that we realize our Essential Nature (puruṣa), which is free

of all craving (vaitṛṣṇyaṁ), even as craving continues to arise in the mind (prakṛti).

Through discrimination of the real from the unreal, and the eternal from the non-eternal Spirit is realized to be free of all taints.

A

satō mā sat gamayā

Tamasō mā jyôtir gamayā

Myṛtyor mā amṛitam gamayā

Om Shanti, Shanti, Shantiḥ

From non-truth, lead me to truth

From darkness, lead me to light

From death, lead me to eternal Being

Om, Peace, Peace, Peace