International Yoga Day, Times Square, NY. @Reutger

Over the last century and a half, yoga has become a global phenomenon. In the process, lines of tension have emerged over what constitutes authentic

practice versus what has been transformed to be “digestible” by a western audience. On one side of the conversation are those who argue that, “anything

goes”–that there is no core essence of yoga, that no one “owns” it, and that practitioners and would-be teachers are therefore free to adapt these

traditions in any way that they like. On the other side are those who argue that yoga does have an eternal and unchanging essence, that it is finally the

cultural property of the people of India, and that those who would seek to “adapt” it to changing times, cultures, and circumstances are engaged in a

neocolonial act of appropriation.

Each of these “sides” has a point.

As many scholars have recently argued, change and adaptation are nothing new for yoga traditions. Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras themselves involve

adaptation and transformation of earlier traditions into a powerful synthesis that has provided the basic template for yoga practitioners for centuries: a

template that itself allows for further development, such as in the area of āsana, or posture. Simultaneously, though, there is something deeply

troubling about the seeming desire of at least some in the yoga world to completely divest these traditions of their Indian origins and their roots in

ancient spiritual traditions: Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain. Is this desire racist? Does it flow from a materialist worldview and a general aversion to all

things that might be seen as “religious”? Or is it some combination of the two?

The conflict between the two dominant approaches to yoga–approaches that we might call secular and traditionalist, respectively–is often

traced by adherents of both approaches to the Indian masters who first brought yoga to the western world, beginning with Swami Vivekananda in 1893. Some of

these Indian masters, such as Vivekananda and Paramhansa Yogananda, to name just a couple, brought yoga as part and parcel of a total spiritual worldview

and way of life. Others, though, tended to present their yoga practice as a secular therapeutic – or even medical – practice of universal value and interest.

And still others, such as Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, initially presented their practice in the more secular fashion, but then gradually made a transition to a

more traditionalist mode of presentation. Even the more traditionalist masters, like Vivekananda and Yogananda, rarely used the word Hindu to

describe their teachings, emphasizing the universality over the Indianness of the philosophy that they were seeking to impart to their followers.

Why did these masters present their teachings and practices in the way that they did? They were, it seems, seeking to balance two concerns. Of primary

importance to them were the teachings and the practices themselves. Swami Vivekananda, for example, whose teachings I know best (both from my scholarship

on him and due to the fact that I am a practitioner in his tradition) was mainly concerned to propagate the practices and ideals of Vedanta far and wide.

He saw Vedanta not only as a type of Hindu philosophy (although he did believe that in the Vedas it had found its purest and fullest expression), but

rather as the universal truth underlying all religions and philosophies. In the famous words of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, “Vedanta is not a religion, but

religion itself in its most universal and deepest significance.” (Radhakrishnan, The Hindu View of Life, p. 18) Vivekananda’s main concern was to

spread this perennial, primordial philosophy.

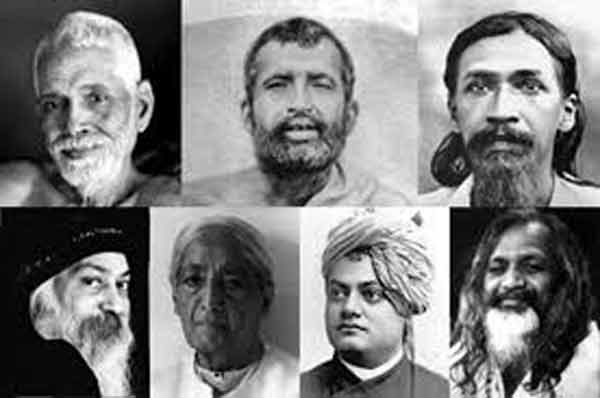

Indian Masters

This “prime directive,” however (to quote Star Trek), leads immediately into the second concern. How does one go about presenting a

practice and a worldview that, until one’s own time, have been ineluctably intertwined with a culture and a set of terms that one’s audience is likely to

regard with contempt? Recall that both Swami Vivekananda and Yogananda brought their teachings to America when India was still a colony of the British.

Recall, also, that the large gap of time between Yogananda and the major wave of Indian yoga teachers that came to the United States in the 1960s was

largely due to the Asian Exclusion Act, which was not repealed until 1965. Those Indian masters who brought their gift of yoga to the west were brave souls

who knew they were walking into a hostile, racist environment. Western racism–ranging from the truly vitriolic to the quiet condescension of regarding

other civilizations as “primitive” or “quaint” – in combination with religious conservatism that viewed Hinduism as a “heathen” faith, meant these early

masters had to tread carefully. In order to reach their audiences–to convey the healing, life-transforming teachings and practices that they so urgently

wished to share–they had to present these in as innocuous and non-threatening a manner as possible. Even then, they were often met with suspicion and

derision. The recent (and I might add, beautifully made) documentary, Awake, on the life and work of Yogananda vividly portrays the very real

heartache of rejection that this great master experienced at several points in his career in the western world. Finally, and this point is probably even

more pertinent today, these masters were also dealing with western rationalism and skepticism. Indian philosophers have of course practiced rational

skeptical inquiry for many centuries, developing logical argument into a fine art. But in the west, skepticism is conflated with materialism, and so with a

reflexive urge to ridicule anything presented as “spiritual” or “otherworldly.”

So what did these masters do? In order to carve out a space for their discourse in the west, they presented yoga and the philosophies associated with it as

scientific – indeed, as empirically testable, holistic approaches to mental, physical, and spiritual wellbeing. And it is not that these are false claims.

Many have been repeatedly tested and verified.

Science, however, occurs in the public square. Its claims are open for all to test, and no one is disqualified from trying to experiment with them.

Protecting the integrity of the yoga teachings requires something more akin to religious authority: something like the teaching authority of the Roman

Catholic Church to define what is and what is not valid Catholic teaching. But this, of course, is precisely what the masters needed to avoid in order not

to be seen as religious proselytizers, competing with Christianity and various other pillars of western civilization to which their radically different

worldviews might be seen as a threat (such as atheism and materialism).

The first Indian masters to bring yoga to the west took a variety of approaches to this dilemma: maintaining the integrity of their teachings through time

while avoiding the pitfalls of being pigeonholed as teaching a religion. Some established organizations that, internally at least, maintain the ancient

Indian tradition of the guru-shishya-parampara, or succession from teacher to student. Many of these organizations maintain publication

enterprises that disseminate the teachings of the tradition in a way that, while avoiding the heavy-handedness of a religious orthodoxy, nevertheless makes

clear what the point of view of the tradition is on the various topics treated in its published works. Others took a more secular route, establishing

teacher training and certification programs with clear criteria for what is correct teaching and what is not. In other words, the individual yoga teachers

did take precautions to ensure the integrity of their teachings.

The current situation, therefore, is not the “fault” of the first Indian yoga masters to come to the west. The situation, rather, is in some ways akin to

what has always been the case within India itself. That is, there are many yoga teachers representing a variety of teaching lineages, each with its own

philosophy and approach to practice. Secondly, most western societies, like India for much of world history, are free societies, in which there is nothing

preventing intelligent and motivated individuals from drawing whatever they like–whatever they feel “works” – from the many approaches available and starting

their own schools of thought and practice. (As I recently argued in another essay for this journal, this is one way of analyzing the origin of Buddhism.

The Buddha did precisely this, drawing meditation teachings and concepts from the yoga masters of his time and from the tradition of the Upanishads, and ascetic and ethical teachings and concepts from the Jain tradition, to develop his own, powerful synthesis which we now call

Buddhism.) The yoga world in the west, one could say, is made up both of persons practicing within established lineages, founded by Indian masters who

brought their universally relevant teachings and practices to the west, and “free agents” who have developed their own understanding and approach to these

teachings, some of whom have set themselves up as yoga teachers in their own right.

On the other hand, there is an important respect in which this situation is radically different from what has obtained traditionally in India. I am

referring to the fact that many of the yoga “innovators” of the west today reject a substantial portion–in some cases, the totality–of the larger

metaphysical worldview and culture taken for granted by the Indian traditions. This, one could argue–and yoga traditionalists do argue–has resulted in such

a massive distortion of yoga practice and philosophy as to make it unrecognizable.

Even when Buddhism was transmitted to the, in many ways very different, culture of China (and from China, to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam), it still

encountered indigenous spiritual traditions, such as Daoism, with which it could assimilate without losing its core integrity. Chinese (and Korean,

Japanese, and Vietnamese) Buddhisms are, in numerous ways, radically different from Theravada or Indo-Tibetan Buddhisms, but they are still recognizably

Buddhist.

This is less obviously the case for contemporary western forms of Buddhism that deny, for example, the phenomenon of rebirth, or that have so psychologized

the concept of karma as to render it but a pale reflection of its Indian original. It is even less clear, then, that yoga exercises performed for no other

reason than having “rock hard abs” bear any relationship at all to the various conceptions of yoga developed in India through the centuries.

This is where the question of the “ownership” of yoga and the desire to “take back yoga” emerges. From a traditionalist point of view–to which I am largely

sympathetic–it is a form of misrepresentation to use the term yoga for a system of exercise with a purely physical focus (with some emphasis,

typically, on stress relief) that has been completely divested of the ontological assumptions that the various yoga traditions have carried with them for

centuries.

Nataraja

Indeed, the situation becomes even more egregious, from this point of view, when the teachers of such systems explicitly reject – or in some cases, even

ridicule – the ancient teachings, dismissing experiences such as samādhi and concepts such as moksha as mere fantasy. A traditionalist will

say, “Yoga without samādhi or moksha? That is the whole point of yoga!”

Now, to most persons, the question of the ownership of a spiritual (or physical) practice may sound quite bizarre. Who is going to come into my house and

prevent me from doing my āsanas? Or enforce the way that I do it? Or the beliefs that I hold or do not hold while doing them? This question becomes less

outlandish, however, when one bears in mind that yoga is now a big business. The issue of the patenting of certain yoga postures has now emerged. This does

not mean that a private individual would have to pay a royalty in order to practice a particular āsana; but it does place restrictions on what one can

teach to others in a public setting. For those familiar with the socio-economics and politics of India, this is disturbingly reminiscent of the patenting

of seeds that have been used by Indian farmers for generations by large, multi-national agribusinesses based in western nations. The transformation of yoga

into a big business, and the domination of that business by persons with, often, little or no connection or sympathy with the ancient philosophies

associated with that term, or with the culture that produced it, clearly raises the spectre of neocolonialism. It is the Monsanto-ization of yoga.

This is a difficult issue to confront, from a traditionalist perspective, because the secularist can say, quite rightly, “I am free to practice whatever I

like and call it whatever I like.” Recent scholarship on yoga has inadvertently given support to this approach; for, as scholars also, quite rightly,

argue, yoga has always been modified and transformed and reinterpreted to suit new contexts. The Indian masters who brought yoga to the west did this very

thing, and quite consciously so. It is important to note that scholars in the field of religious studies, at least in our role as scholars in this field

(and yes, I am one of these folks), are obligated to present the materials that we study in as value-free and objective a fashion as possible.

As a result of the strictures of this field, there are no criteria within the academic study of religion by which to say that one form of yoga practice is

more or less authentic or valid than another. Each is just another iteration of what people choose to call yoga.

People wear many “hats,” however. One cannot say, on the basis of objective scholarship, that this or that form of yoga is authentic and this one is not.

This is what yoga traditionalists have been trying to do: to differentiate between “real” yoga and the kind of body-focused practice that has divested

itself of the metaphysical view of reality that is shared almost universally among ancient indigenous Indian traditions (the ancient materialist Lokāyata

or Cārvāka school of thought being the noteworthy exception).

I would like to propose a different strategy

for yoga traditionalists.

The idea of authenticity is a dangerous mirage.

It traps one into an authoritarian discourse

in which one seeks to tell others

what they can or cannot practice:

a losing battle in a free society.

What one can argue, on an objective basis, is that particular forms of yoga have beneficial effects–mental, physical, and spiritual–that others do

not. Studies can be done, and have been done in the dozens, maybe even the hundreds, on the health effects of yoga practice. Perhaps a study could be

undertaken with a control group of yoga practitioners with no particular ontological or spiritual belief connected with their practice and a set of yoga

traditionalists, whose practice includes an aspiration toward moksha, an experience of bhakti, and so on, to see which practice is actually more

beneficial, in an empirical sense.

One can also argue, perhaps not in one’s role as a secular scholar of religion, but as a philosopher (and I am also one of these folks), that the worldview

with which yoga is traditionally associated has its own integrity and advantages not shared by materialism.

I have already argued (again, in an earlier article for this journal) that materialism has significant drawbacks in explaining, for example, certain

puzzling phenomena, such as the past life memories of the boy named Ryan, investigated by Jim Tucker as narrated in his book, Return to Life.

What I am proposing, in other words, is an argumentative approach to the global yoga phenomenon. Traditionalists have been fighting the losing battle of

arguing that the form of yoga they prefer is better because it is authentic and that the more body-centered forms of yoga are not. I propose that

traditionalists should argue that the form of yoga they prefer is better because it is better. Not only does it produce the aims for which those who do

yoga for purely physical reasons are aspiring. It also leads to samādhi, and to liberation from the cycle of rebirth. One suspects that traditionalists

have generally not taken this line of argument because they know that they will likely be ridiculed by their interlocutors. “What samādhi? What liberation?

What cycle of rebirth?” The truth is, though, that the clash in the world of yoga is not merely a clash of cultures. It is a clash of worldviews. And

clashes of worldviews are best resolved in the arena of philosophical debate. May the best argument win! Satyameva jayate!