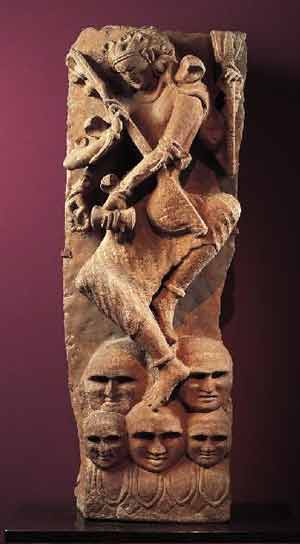

A Shiva panel from the Kailash temple (Cave 16), Ellora. QuartierLatin1968

Introduction

Modern scholarship now frequently acknowledges that the concept “Hinduism” was constructed by Western ‘Orientalist’ [1] scholarship, and that there was no such indigenous term until the nineteenth

century.[2] Yet such acknowledgment is often merely lip-service, for the term continues

to be used to describe the entire complex and diverse Indian religious milieu, other than Buddhism and Jainism, throughout the common era. Though there is

utility to an etic (non-indigenous) term that scholars define clearly and use specifically, this is not such a term, and it remains true that we have not

yet unpacked the manifold implications of the fact that as a premodern religious (as opposed to cultural) designator, “Hinduism” is fundamentally

a fiction, there being no single religious practice or belief that unites all putative “Hindus” in the premodern period. It is a fiction that has obscured

our ability to discern clearly the complex interrelationships of the competing religions of the volatile and productive medieval period. An examination of

the primary sources for this period shows us five primary religious traditions, each seeing themselves as a distinct and complete path to liberation as

well as a vital cultural institution competing for patronage: those of the Vaidikas, Śaivas (including the Śāktas), Vaiṣṇavas, Bauddhas, and Jainas. [3]

The purpose of this essay is twofold: in Part One, I seek to identify Shaivism as a distinct religious institution in the early medieval period (600-1100

ce) that certainly did not see itself as part of a “Hinduism,” since that concept didn’t exist in this period; but neither did it see itself as part of

Brahmanism, the tradition that is the antecedent to Hinduism. In Parts Two and Three, I seek to delineate the doctrines that made Shaivism distinct from

other medieval Indian philosophies (with which it was of course interrelated, just as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are interrelated), that we readers

may have a clearer picture of the Śaiva religious-cum-philosophical textual landscape of the period. In this article I draw heavily on the work of Alexis

Sanderson (and his students), work that culminated in a book-length 2009 study demonstrating the dominance of Shaivism as a distinct religious institution

throughout South and Southeast Asia in this period.[4]

Shiva as Lord of Dance and Music, 11th century India:

Orissa, 1000-1099 Sandstone 45 x 17 x 10 in.

Carved in deep relief, the figure of Shiva is

depicted dancing on a pyramid of five heads with

sunken eyes placed upon a lotus base.

Five heads or skulls play an important

role in esoteric tantric practices.

Part I: Evidence for Shaivism as a single religion in the early mediaeval period

Before addressing what distinguished Śaiva thought within the broader sphere of Indian intellectual activity, we must define Shaivism as an entity. We may

begin by briefly examining evidence that Shaivism was a single self-contained religion and thought of itself as such. By “religion” I mean “an institution

consisting of culturally patterned interactions with culturally postulated superhuman beings” (Melford Spiro’s famous 1966 definition), to which I would

add the clause that religion is also an institution that offers its adherents either salvation or heavenly rewards or both. In the Indian milieu, where

religious traditions often are not clearly demarcated, we must also ask what circumscribes and differentiates one religious tradition from

another. I see these five criteria as operative (in order of importance): 1) a body of texts that belong to that system and no other; 2) authoritative

teachers consecrated in that system and no other; 3) the fact that the system makes an effort to distinguish itself from others; 4) competition with other

religious systems, such as the claim to offer definitive salvation above and beyond them; and 5) the belief in a founder, usually conceived as historical,

and unique to that system. Shaivism possessed all of these in the period in question.

To take the last first, Shaivism as a distinct initiatory religion (as opposed to a non-initiatory devotional tradition) did have its putative historical

founders, though their historicity is heavily obscured by hagiography and myths. The earliest instantiation of sectarian monotheistic Shaivism for which we

have certain evidence is that which became known as the Atimārga (‘Higher Path’), more commonly designated by one of its three primary branches: the

Pāśupatas, Kālamukhas, and Kāpālikas. All three are explicitly part of one tradition, though, putatively founded by one Lakulīśa, thought to be an avatāra of Śiva, who is said to have descended in a cremation ground and animated the body of a deceased brāhmin to reveal his teaching to the

world.[5] That Lakulīśa was possibly a historical figure (though the name was invented

later) can been seen in the accounts of his religious instruction to three or four named primary disciples, at least one of which (Kuśika) began a lineage

that is documented for ten generations.[6] The second and substantially larger

instantiation of initiatory Śaiva religion (śiva-dharma[7]) called itself the

Mantramārga (known to scholars as Tantric or Āgamic Shaivism), putatively founded by one Śrīkaṇṭha Nātha, also identified as an incarnation of Śiva. His

teachings were the five “streams” (srotas) of the Śaiva scriptural corpus.[8]

As has now been well documented, these Mantramārgic scriptures offered detailed cosmologies and rituals unique to Shaivism. Foremost amongst the latter was

the unprecedented (apūrva) claim to offer a salvific initiation (the nirvāṇa-dīkṣā)—which could be conferred only by a

consecrated Śaiva guru temporarily or permanently identified with Śiva—that guaranteed liberation at or before the time of one’s bodily death.[9] Further, these scriptures taught unique theological doctrines (e.g., the three malas, five Acts of God [pañca-kṛtya], five kañcukas, 36 tattvas, and so on), and argued that only liberation achieved

through Śiva’s scriptural teachings is true and final liberation. More specifically, Śaiva theologians had an inclusivist view which taught that the other

Indian religions granted some salvation from bondage and suffering, but argued that their soteriological goals do not reach to the highest levels

of reality,[10] i.e. the Pure Universe (śuddhādhvan) where only God exists,[11] which is attained only through Shaivism, they argued. [12] Thus Shaivism fulfills the first and fourth criteria listed above.

To address the third criterion: Buddhism and Jainism are generally regarded as separate religions from Brahmanism/Hinduism specifically because they

explicitly reject the spiritual authority of the Veda and are therefore labelled as heterodox (nāstika). [13] But precisely such heterodoxy belongs to Shaivism in varying degrees (especially

in its Śākta dimension). Here is the evidence for that assertion. First, Śaiva sources of the early mediaeval period argue that whenever Śaiva and Vedic

injunctions conflict, the Śaiva one supersedes the Vedic. Śākta-Śaiva exegete Abhinavagupta (c. 1000) writes in the Tantrasāra (ch. 4), “The

capacity for annulment belongs to the Śaiva scriptural injunctions alone, as established by reason and by countless scriptures.” [14] Even the more conservative Śaiva scriptures argue that Vedic injunctions are

valid only in the sphere of civic religion, and that the Veda has no soteriological value to the initiated Śaiva. [15] Though most texts do recommend that the initiate maintain his Vedic religious

duties, these must be understood by him as being done purely for the sake of appearances, to uphold the established social order. In fact, we are

told, if one makes the mistake of believing that it is the Vedic observances in combination with the Śaiva that have religious value, then neither

will bestow their respective benefits, for a hybrid practice (śabala-karma) is said to be fruitless. [16] Abhinavagupta goes further in asserting that the Vedas are not only

soteriologically irrelevant, but in fact “drag down [into a lower birth] those whose minds are deluded“ (TĀ 37), i.e., those who believe the Vedas will

liberate them. Indeed, it is said in the scriptures that when Śiva’s blessing descends on a ordinary Vaidika, it takes the form of the realization that his

Vedic practice is inadequate and thus leads him to seek a Śaiva Guru.[17]

Shiva Mahadeva in 8th-century Kashmiri sculpture.

Cleveland Museum of Art. 1989.369

The objection might be raised here that I am engaged in constructing a category just as artificial as that of Hinduism, and that instead of a single Śaiva

religion I should see merely a collection of interrelated sects and cults. Yet the Śaivas in the early mediaeval period themselves believed in the

existence of a coherent Śaiva religion, for we have evidence that they viewed the members of the other Śaiva sects as co-religionists, no matter how far

removed they were in doctrine or practice, and did not view Vaiṣṇavas and others as co-religionists. We see evidence of this in both scriptural and

exegetical writings; for example, in his Tantrasāra, Abhinavagupta quotes the Pārameśvara-tantra, which says, “All these Vaiṣṇavas and

others are stained by limited knowledge and attachment. They do not discover the highest reality, being deprived of the wisdom of the Omniscient One,” to

which he adds the comment, “Thus they do not look to the higher View (darśana), and therefore, they are simply averse to correct discernment, true

scriptures (sad-āgama), and the instruction of true Gurus. It is only those who are pierced by an intense and stable Descent of Power ( śaktipāta) from Śiva, [and who subsequently] refine and purify their conceptual understanding through true scriptures and [a true Guru], who

[finally] enter their own ultimate nature.”

An important piece of evidence that Śaivas saw their religion as coherent as well as distinct has been already pointed out by Sanderson: that of the rule

of supplementation outlined by Jayaratha in his Tantrāloka-viveka.[18] This

is the rule that whatever detail is missing from one’s primary source-text (mūla-tantra) is to be supplemented from other texts within the Śaiva

canon, even if the proper performance of a single ritual act thus requires a combination of information from multiple texts (four, in the example), the

collation of which crosses several sectarian and doctrinal boundaries but remains within the Śaiva canon. Sanderson argues that the entire Śaiva canon of

many hundreds of scriptural texts “is seen as a single complex utterance” (2005: 23). Thus our first criterion is yet further strengthened.

For further evidence that Śaivas thought of themselves as constituting a distinct religion, we may briefly mention the rite of li ṅgoddhāra. This is a special ritual designed for those who wish to convert to Shaivism from another dharma; it is designed to

remove one’s former sectarian marks (the visible and invisible defining features of one’s religious identity) so that one may be initiated as a Śaiva.

Anyone performing a soteriologically-oriented practice in another tradition prior to coming to Shaivism had to undergo this rite in the period we are

discussing; note that this was just as true for a Vedic sannyāsin or vānaprastha as for a Buddhist or Vaiṣṇava. [19]

Finally, clinching evidence is found in the fact that the Vaidikas also confirmed Shaivism’s status as a separate religion: an inferior one to be

repudiated. Texts such as Medhātithi’s Manusmṛti-bhāṣya condemned Śaivas as well as Jainas and others as

“outside the Veda” (veda-bāhya) and therefore having no religious value.[20]

The Vaidika Purāṇas labelled Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava Tantric texts as ’scriptures of delusion‘ (moha-śāstra). [21] The seventh-century exponent of Vedic orthodoxy, Kumārila, even argued that some

Śaivas were further from the norms of the Veda than Buddhists and Jains, due to their impure and foreign/barbaric (mleccha) practices

such as eating from a skull-bowl.[22] The famous upholder of Brāhminicaldharma Aparāditya cautioned the true Vaidika against adopting Shaivism, and presents a detailed argument against Śaiva doctrines. [23]

Next month: Part Two: Shaivism’s Sources and Influences