Author's Note: This begins a three part article giving insight into the traditional six Vedic seasons. In my previous article about the zodiac, I compared its seasonal and stellar correspondences. Here, we explore the seasons to understand the tropical zodiac, before later going into the stars. Here, we aim to get a deep felt-connection to the seasons on a physical, emotional and astronomical level.

Rtu Chakra Wheel of the Seasons by Freedom Cole

In Charaka Saṁhitā, the year is divided into two halves, each divided into three portions of two months.

The solar half of the year is from winter solstice to summer

solstice. It is called the northward course (uttarāyana) where the days of the Sun lengthen.

The lunar half of the year is from summer solstice to winter solstice, and is called the southward course (dakṣināyana) where the nights of the Moon lengthen.

Charaka divides each half-year into three seasons, making the six traditional Indian seasons.

Each of these seasons is divided into two seasonal months.

Two Halves of the Year

The two halves of the year can easily be described as being divided by the two solstices. In this context, uttara means north (or upwards) and ayana means roadway, or course. Dakṣiṇa means south (or rightside). The two halves are called the southern and northern course of the Sun

respectively.

In the image below,

the Sun rises at 30° southeast on the winter solstice. At the equinox it rises at directly 90° east. On the summer solstice it rises at 60° northeast. On

each day of the northerly course (Uttarāyana), it rises more and more towards the north. After the summer solstice, the Sun begins to rise more

towards the south each day, which creates the southerly course (Dakṣiṇāyana). The movement of the Sun in these two directions creates two

astronomical halves of the year.

Uttarāyana

is also the Sun’s movement from its lowest point in the sky (closest to Earth) at the winter solstice, towards its highest point in the sky at the summer

solstice. Dakṣiṇāyana is the opposite motion, where the Sun becomes lower and lower in the sky. In Uttarāyana, shadows get shorter as the Sun gets higher in

the sky. In Dakṣiṇāyana, shadows get longer as the Sun gets lower and has more of an angle to create shadows. The shadow length can be observed on

a sundial, and indicates the day of the month. As the shadow shortens, our outward nature grows. As the shadow lengthens, the internal - emotional world grows. This cycle relates to the breath of the year. Uttarāyana is the exhalation, while Dakṣiṇāyana is the inhalation. The

exhalation takes us outward and the inhalation brings us within. The solstices are the points in between the in and out breaths.

Seasons (Ṛtu)

|

Uttarāyana

|

Sun

(Agneya)

|

|

Śiśira: Cold Season

|

Maruts

|

|

Vasanta: Spring

|

Vasus

|

|

Grīṣma: Summer

|

Rudra

|

|

Dakṣiṇāyana

|

Moon

(Saumya)

|

|

Varṣa: Rainy Season

|

Ādityas

|

|

Śarad: Autumn

|

Viśvadevas

|

|

Hemanta: Winter

|

Maruts

|

Each half-year is divided into three seasons (ṛtu). Half the seasons are solar, and half are lunar. These seasons are particular to Southeast

Asia, but the way of looking at them can deepen the way we look at seasons anywhere. Spring (vasanta) marks the head of the year and lasts

approximately 60 days. It is followed by Summer (grīśma), which is extremely hot in Asia. After this come the warm rains in the Rainy Season (varṣa). This is followed by the Autumn (śarad), which is a time of harvest. Then comes the first phase of Winter, called hemanta

, followed by the second phase called śiśira. These two phases together are often called Winter, and the Cold, or Cool, Season.

In the Vedic period, deities ruled each of the seasons, and they were called on during prayers. Spring is ruled by the Vasus (the shining ones);

Summer by the Rudras (destruction gods); and the Rainy Season by the Ādityas (creative potency of the forms of the Sun). Autumn is ruled

by the Viśvadevas (universal principles), and the Winter seasons are ruled by the Maruts (wind gods).

In the Atharvaveda, the deities of the seasons were invoked in prayer, while later the seasons themselves were invoked. After the invocation of

the seasons in the Taittirīya Saṁhitā (VII.1.18.1-2), the worshipper says:

“Holy order have I placed upon truth; truth have I placed upon holy order.”

The seasons (ṛtu) are seen to be the force of the Natural or Divine Order (Ṛta). There is law that is made by mankind, and then there is

‘that which is natural’ to the Universe:

the way things are – Ṛta. The seasons cyclically

unfold in their natural order. They are the external manifestation of the Natural Order of the Universe. By aligning ourselves with the seasons in ritual

and lifestyle, we are aligning with the Divine Order.

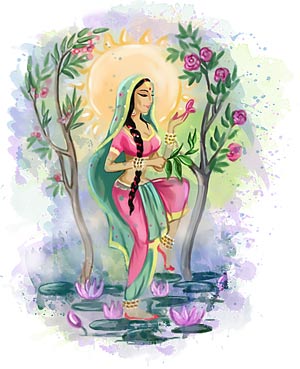

Varshadevi - Rainy Season

There are certain Vedic rites performed with the fruits or grains of the particular season.

The Spring was offered the life-sap/juice (rasa); >the Summer given barley (yava); and the Rains were given the healing medicine (auṣadhi). The Autumn was given rice (vrīhī); the Winter was given pulses (māṣa); and the Cool Season was given sesame seeds (tila).

It is said that the seasons made Prajapati sacrifice in this way, and then Prajapati made Indra sacrifice accordingly. The Vedic texts often performed

seasonal rituals as part of their sacrificial practices. The hope was to propitiate the season so that it would yield good results. For example, by

ritually making the Rainy Season happy, the rains would come on time and release in the proper amount (no late rains that kill the planted seedlings, or

excess rain that washes them away).

Tāntrik

literature divided the day into six portions of four hours, and mapped the different seasons onto the day. This is used to ensure that specific rituals are

performed at the time that correlates to the desired effects. The seasons can also be found overlain on the breath. Uttarāyana is the exhalation,

and Dakṣiṇāyana is the inhalation. As each half of the year is divided into three parts, so the breath is divided into three natural parts.

Vasantadevi - Spring

After the lungs have been completely filled, the exhalation quickly comes out (Śiśira) and then it balances its force (Spring) and exasperates

itself at the end of the exhalation (Summer). The Rainy Season is the beginning of the inhalation, gasping to fill with breath; while the Autumn is the

balanced, even exhalation, and the Winter is the final slow filling of the inhalation. The middle of the breath is naturally more balanced, and this is the

location of the equinoxes. The goal of the yogin is

to slow the beginning of the breath and extend the end of the breath, so that the entire inhalation and exhalation have an even force.

Coming to Śiva’s Wedding

The seasons can be anthropomorphized as living beings. They come to the sacrifice in the Vedic literature to partake in the Soma. In the Taittirīya Brāmaṇa (III.10.4.1) they are seen as parts of a bird, with Spring as the head, the Winter months as the body, Summer and Autumn the

wings, and the Rainy Season as the tail. In the Puruṣa Sūkta, when the gods performed the cosmic sacrifice, the Cosmic Person (Puruṣa)

was the offering, Spring was the ghee, the Summer was the fuel, [the Rains were the purificatory water], and Autumn was the offering food.

The seasons come as beautiful women dancing to Śiva and Parvatī’s wedding in the Purāṇas.

They are each wearing the elements of their season. Spring has anklets made of bees as she walks upon the lotuses of the forest. She holds a mango branch

with fresh sprouts. Everything sprouts, grows, and flowers where she walks. Śiva and Parvatī relate to the Sun and Moon; and the seasons dancing at their

wedding is an archetypal image of the Natural Order.