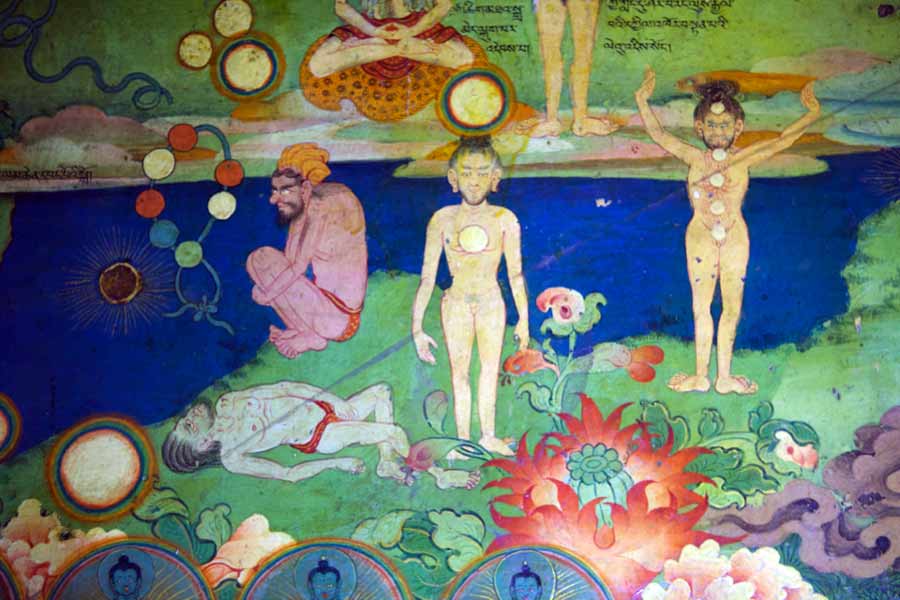

Bhutanese yogi in posture of Garuda

Editor’s Note

Born in New York City, Ian has lived the majority of his life in Asia, and has transformed his love of mountain climbing, philosophy, art, and exploratory

travel into a fascinating career. In 2001, he was honoured by National Geographic Society as one of seven “Explorers for the Millennium” for his research

and discoveries in southeastern Tibet.

Ian is the author of seven critically-acclaimed books on Himalayan culture, traditional medicine, Buddhism, and yoga. His literary chronicle of a series of

ground-breaking expeditions into the world’s deepest gorge The Heart of the World: A Journey to Tibet’s Lost Paradise was published by Penguin Press.

His latest work, Tibetan Yoga: Secrets from the Source will be launched in fall 2016.

Ian is the curator of Wellcome Collection’s major winter exhibition, ‘Tibet’s Secret Temple’, which uncovers the mysteries of Tantric Buddhism and the rich

history of its yogic and meditation practices. Taking inspiration from a series of intricate murals that adorn the walls of the Lukhang Temple in Lhasa,

Tibet, the exhibition showcases over 120 outstanding objects from collections around the world that illuminate the secrets of the temple, once used

exclusively by Tibet’s Dalai Lamas - secret temple

Click Here to view 'Tibet’s Secret Temple' Gallery in Sutra Journal.

Vikram Zutshi:

How did you find your way to Tibetan Buddhism? When and why did you decide to make a career out of it? What is your specialty within this field?

Ian Baker:

My introduction to Tibetan Buddhism occurred in 1977, when I went to Nepal to learn traditional Tibetan scroll painting. I became increasingly intrigued by

the complex symbolism of Tibetan art and the philosophical richness that underlies its aesthetic forms. While in Kathmandu, I also met a great Tibetan

Buddhist master, Chatral Sangye Dorje Rinpoche (who passed away on December 31, 2015 at the age of 102). Because of my interest in Tantric Buddhist

practices and artistic traditions, I returned to Nepal in 1984 as Academic Director of a US-based college semester abroad program. I ran the program until

1990, spending most of my summers in Tibet or in remote regions of the Himalayas, at the instigation of Chatral Rinpoche. My interest in Tibetan studies

centred on its non-monastic yogic traditions and, in particular, on the ways in which landscape and environment can support a transformed experience of the

human condition.

Vikram Zutshi:

Tell us about your book The Heart of the World. What are the biggest lessons you took away from the journey? Are there any other mythical places left to

discover in the Himalayas that you're aware of?

Ian Baker:

The Heart of the World is a book that chronicles my exploration of the Tibetan tradition of beyul, or ‘hidden lands’. Beyul are places where the physical

and spiritual worlds are said to intersect and where meditative and yogic practices are said to be especially effective. Located in remote regions of the

Himalayan mountain range, beyul are also places known for their extraordinary bio-diversity and physical beauty. The biggest lesson that I learned from

staying for extended periods in several such hidden-lands is that wild and untamed landscapes can open us to dimensions of experience that are often

overlooked in more tempered environments. There are many such beyul, hidden throughout the Himalayas as well as in other parts of the Earth. According to

Tibetan tradition, the greatest of these hidden-lands is Beyul Pemako, at the eastern edge of the Himalayan range. Like all beyul it is described as having

outer, inner, secret, and ‘innermost secret’ dimensions. I will be returning to Pemako later this year to follow a route that’s said to lead into its

innermost recesses. The Tibetan texts liken Pemako’s innermost reaches to the womb of the Tantric goddess, Vajra Varahi, whose terrestrial body forms

Pemako as a whole.

Vikram Zutshi:

What are the main tenets of Tibetan Buddhism and how is it distinguished from the Buddhism practiced in Thailand and Sri Lanka?

Ian Baker:

Tibetan Buddhism derives from the Vajrayana, or Tantric form of Buddhism that originated in India and developed, in textual form, from the eighth century

onward. Unlike the earlier forms of Buddhism that are practiced in southeast Asia, Tibetan Buddhism advocates a less renunciatory approach to human

existence that’s based on engaged compassion and dynamic interaction with the sensory world.

Detail from Lukhang murals showing meditation on internal and external lights by Ian Baker

Vikram Zutshi:

What are the different schools of Buddhism within Tibet? What are their defining characteristics?

Ian Baker:

The many streams of Tantric Buddhism that entered Tibet from the eighth century onward are currently classified into four major schools: the Nyingma, the

Kagyu, the Sakya, and the Gelug. To generalise, the earlier transmissions of Vajrayana Buddhism to Tibet emphasised non-monastic yogic practices that

became less prominent in the later reformed Gelug tradition that places more importance on scholastic study and monastic ritual. Tibet’s indigenous

pre-Buddhist tradition of Bon has also deeply influenced Tibetan Buddhist practice, especially at the level of the general populace. At the same time, Bon

has incorporated much from Buddhism and has its own independent transmission of Dzogchen, the ‘Great Perfection’ teachings that represent the culmination

of the spiritual path and ultimately transcend their cultural origins.

Vikram Zutshi:

What are the origins of the Kalachakra initiation? What are the differences and similarities between Tantric Buddhism and Indian Saiva soteriology?

Ian Baker:

The Kalachakra Tantra was the last great literary production of Vajrayana Buddhism in India, appearing at the end the 10th century and

attributing its origins to teachings given by the Buddha to a king who asked for a path to enlightenment encompassing of his worldly responsibilities and

proclivities. As the ‘Wheel of Time’, the Kalachakra is vast in scope and emerges out of an ancient Indian myth that is reformulated in the context of the

Kalachakra Tantra as the Kingdom of Shambhala, an enlightened realm into which those who receive the Kalachakra Tantra initiation from an authentic source

will ultimately be reborn. All of the Buddhist Tantras, and the later so-called Yogini Tantras in particular, draw actively from concurrent traditions of

Tantric Saivism, thus extending the reach of Buddhist ideals beyond their conventional monastic settings and embracing more dynamic forms of contemplative

practice.

Vikram Zutshi:

Tell us about your studies in the Tibetan healing arts and the book that came out of it. What are the some of the commonalities and differences in Tibetan

medicine, Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine?

Ian Baker:

I studied traditional Tibetan Medicine in the 1980s, while living in Kathmandu. My particular interest was in what is called in Tibetan Chod-Men, or the

synthesis of Buddhism and the healing arts. The inner practices of Tantric Buddhism are deeply embodied and involve increased attention to physiological

processes. The practices of the Inner Tantras are also actively enhanced through the use of supporting medicinal formulas. I wrote about this in my book

The Tibetan Art of Healing as well as in The Heart of the World. Tibetan Medicine is very rich in that it integrates traditional Indian and Chinese

practices and pharmacological knowledge into its diagnostic and curative methods. It is further enhanced by its active incorporation of Tantric practice

and insight into psycho-physiological processes within the human body.

Folios from a Dzogchen practice manual, Royal Library, Copenhagen

Vikram Zutshi:

What are the defining characteristics and central themes of Tibetan art? What are the significant periods for the flourishing of art and the main schools

that emerged?

Ian Baker:

Tibetan Buddhist art can be seen as an attempt to represent knowledge of the unseen world in aesthetic and visual form. For what was once a largely

illiterate populace, symbolic depictions of Tantric Buddhist deities became a means for conveying the essential meaning of the Buddhist path of wisdom and

compassion. Deities in Tibetan Buddhism are ultimately understood as reflections of our inner, and mostly unrealised, qualities and attributes. They are

thus shown in peaceful, passionate, and fierce manifestations to bring awareness to the need for transforming emotional afflictions of greed, anger, and

unmerited fear. Bronze casting as well as scroll and mural painting in Tibet were influenced by Newar art of the Kathmandu Valley, by Pala Dynasty India,

as well as by artistic traditions in Kashmir. Later traditions of Tibetan Buddhist art, particularly representations of the natural environment, were

strongly influenced by Chinese landscape art.

Vikram Zutshi:

Tell us about your latest book on the Dalai Lama's Secret temple. How do the findings in the temple affect yogic practitioners today? Please describe the

style and central themes of the artwork found within.

Ian Baker:

One of the strongest examples of Tibet’s syncretistic artistic tradition can be seen in the Lukhang, a residential temple built for the Sixth Dalai Lama at

the end of the 17th century. The murals in the Lukhang’s uppermost chamber comprise a visual encyclopaedia of the path to enlightenment and were

originally intended as a meditational support for Tibet’s supreme spiritual rulers. The current Fourteenth Dalai Lama specifically requested me to write a

book about the murals as he felt that the teachings that the murals reveal might otherwise be lost. He described the murals as ‘jewels’ of Tibetan

civilisation. My book, The Dalai Lama’s Secret Temple, elucidates the content of the murals which are based on Dzogchen, or ‘Great Perfection’,

teachings revealed by a 15th century Bhutanese master named Pema Lingpa, who was an ancestor of the Sixth Dalai Lama. There are three principal

murals in the room that was once a private meditation chamber for the Dalai Lamas. One mural depicts Tantric Buddhist masters known as Mahasiddhas. Another

mural shows yogic practices for opening subtle energy channels within the physical body. The third mural illustrates visionary meditation practices for

ultimately attaining a rainbow light body. All three of the murals show ways in which yogic practice harnesses physiological, respiratory, and hormonal

processes to transform the human condition. As the Dalai Lama hoped, the contents of the murals are now reaching a wider audience both through the book, to

which he contributed an introduction, as well as by the current ‘Tibet’s Secret Temple’ exhibition at London’s Wellcome Collection.

Between-Earth-and-Heaven

Vikram Zutshi:

How are Tibetan forms of physical yoga different from Indian Hatha Yoga? What are the differences and similarities in their internal energetic maps and

psychophysical hierarchy?

Ian Baker:

Tibetan yoga is called Trulkhor, which can be translated as the ‘wheel that purifies illusion’. The core movements are performed with the breath held below

the abdomen while drawing internal energy into the body’s central axis to stimulate hormonal secretions and free the mind from habitual patterning. The

sequences are more akin to dynamic forms of Chinese Chi Gong than they are to Indian Hatha Yoga, but they share the same ultimate objective of transforming

human experience. One significant difference between Trulkhor and Modern Postural Yoga is that Trulkhor is undertaken specifically as a preparation for

advanced forms of bioenergetic meditation, whereas for most yoga classes today comparable exercises are performed primarily for physical health and

wellbeing.

Vikram Zutshi:

You are curating an ongoing exhibit at the Wellcome collection in London called ‘Tibet's Secret Temple’. Please describe the central theme and some of the

important displays in the exhibit. Why are these carefully guarded secrets being made public?

Ian Baker:

‘Tibet’s Secret Temple’ is an exhibition at London’s Wellcome Collection that will continue until February 28, 2016. The exhibition’s central feature is a

life-size recreation of the Lukhang murals that can be viewed close up in incredible detail. Although these murals, and the yogic methodologies that they

reveal, were once deeply guarded secrets, the current Dalai Lama has actively endorsed the exhibition and hopes that the murals will provide important keys

to humanity’s ultimate potential. In the context of the exhibition, the murals are approached through a series of interconnected rooms that place the

contents of the murals in historical and cultural context and focus on related topics such as Tibetan Medicine and Tantra. There are also several video

installations that contextualise and expand on what can be seen in the murals. Some of the associated art in the exhibition is drawn from the Wellcome

Collection’s archives and some of it is on loan from museums and private collections. Some of the most engaging objects were commissioned in the Himalayan

Kingdom of Bhutan and provided with the support of Bhutan’s Royal Family.

Tibetan Yogini meditating with belt for support

Vikram Zutshi:

The Wellcome site says that "the final room of the exhibition explores scientific investigations into these once secret practices of Tantric Buddhism and

their impact on psychological and physiological health and understandings of human consciousness". Can you elaborate on the scientific research being

conducted in this area and what are the major findings?

Ian Baker:

The final room of the ‘Tibet’s Secret Temple’ exhibition centres on a 15-minute video presentation that includes the perspectives of a Tibetan lama, a

scientist engaged in the study of the neurological correlates of consciousness and compassion, and educators involved with the application of mindfulness

training in educational and clinical settings. The topics that they discuss in the video will be enlarged upon in forthcoming events at Wellcome

Collection, in particular a Mindfulness Symposium that will take place on February 20. The Dalai Lama initiated the dialogue between science and Tibetan

Buddhism in the 1980s and technological advances today reveal ever more supporting evidence for the ways in which the autonomic nervous system can be

positively effected by yogic interventions. Much of the research has focused on clinical applications of Mindfulness training in the treatment of anxiety

and depression, but more recent work is also addressing the ways in which Open Presence meditation – akin to Dzogchen – effects the brain in entirely

different ways, localising activity in the Hypothalamus. Other contemporary research is showing the ways in which breath retention techniques analogous to

Tummo, or the Tibetan yoga of ‘Inner Heat’, stimulate the production of mood enhancing neurotransmitters such as Dopamine as well as positively influence

the human immune system. Perhaps the most revealing aspect of current research is the articulation of hormesis, a neurobiological phenomenon whereby a

beneficial effect (stress resilience, improved health, growth or longevity) can result from potentially dangerous activities such as yogic breath suspension

and alteration of the blood supply to the brain, as illustrated in the Lukhang murals. As the Dalai Lama has said, altering physiological processes in

deliberate and systematic ways can increase strength and resilience, but can also lead to sudden death! It’s for such reasons that the yogic practices

depicted in the Lukhang murals were only to be undertaken with the guidance of an experienced teacher. Nonetheless, they can open our eyes and imagination

to unimagined possibilities of the human condition. I will be writing more about this in a forthcoming book entitled Tibetan Yoga: Secrets from the Source.

Click Here to view a photo gallery of images by Ian Baker in Sutra Journal.